Why Pepsodent made for a good cue and pros and cons aren't nearly enough

The value of cue-based planning and the perils of narrow framing

Hello friends 👏

Welcome to another edition of Curiosity > Certainty!

The topic I write about most is decision-making, followed by habit-building and mental models. Up until eighteen months ago I didn’t know much about any of this stuff. It started with me wondering if there was a better way to handle situations I found myself in at work. Work was new, I was responsible for a new team, and COVID wasn’t kind. As I took to reading and listening, I bartered ignorance for discovery. And recording my thoughts proved to be a good way to fill the gaps in my head. Until now.

From now on, I also want to have a conversation. I want to know what it is that I write about that connects with you. And what doesn’t. So that I can optimize for you, the reader. Because what I share is incomplete in and of itself. Meaning is at the service of the beholder.

With the opening credits past us, let us dive into this week’s movie.

How to make cues obvious and do better than just want to change

Pros and cons and the perils of narrow framing

How to widen the decision-making frame

And a bonus piece on why we, unlike our parents, are purpose-maximizers.

Have you noticed your cue?

One doesn’t need to be a hypnotist today to convince anyone of the need to brush their teeth. But in the early 1900s, even such a person wasn’t enough.

Poor oral hygiene was the norm in the US. Prosperity had brought sugar and chocolate. The US Army had listed poor dental health as a key reason for soldiers being unfit for service. Pepsodent employed Claude Hopkins, the Don Draper before broadcast television, to conceive of a campaign that would help sell their toothpaste.

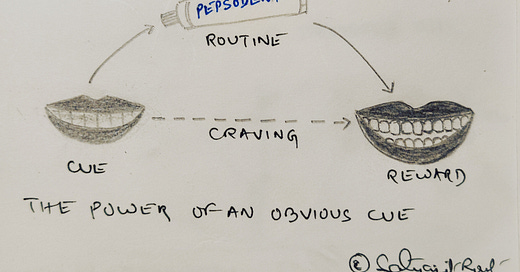

He came up with an idea for a campaign that marketers have since then employed and re-employed with success. The idea was simple: 𝐂𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐚 𝐜𝐮𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐮𝐧𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞 (film covering your morning teeth) 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐢𝐞 𝐢𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐫𝐞𝐰𝐚𝐫𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞 (beautiful smile).

This is nothing but the first law of behavior change in practice. Make the cue obvious.

It is no use if you buy fruits for the week but leave them to rot in the bottom shelf of your refrigerator. Or buy running shoes but keep them hidden in a box. Or dumbbells in the loft, weighing scale in the attic, and so on.

There are so many things competing for our attention that it is easy to miss clues. Much like endcaps in the supermarket are the most prized real estate, you should make all those cues clear and obvious that push you toward your desired behavior change.

Keep those fruits on the dining table, muesli at eye level, and books by the bedside. If you aren’t sure if you’re doing enough, invite a neighbor into your home and ask them to guess the habit you’re trying to build.

And just like marketers pump color and glitz into product promotions, you ought to load your environment with unmistakable clues for the treasure you’re seeking.

For Pepsodent more than a century ago, that cue was the film you felt when you slid your tongue across your teeth. It was the trigger that something stood between you and your ideal of a beautiful self. A tube of toothpaste in your bathroom thus led to a morning ritual.

There are many ways to create rituals. At the start of them all is a powerful and obvious cue. Curious to know from marketer friends how they nudge with the power of cues and reward.

A way of starting a habit that will last

I’ve decided to start eating healthy several times in my life. Any success has only lasted a short period. And then, like a rubber band, I’ve snapped right back. This is called regression to the mean but you don’t need to know that to get what I’m talking about. Because we’ve all been there.

My cues fell short by not being specific enough. When you’re trying to start a new habit, you don’t want to leave any room for doubt or second-guessing.

𝐖𝐞 𝐟𝐢𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐭 𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐢𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐢𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐫, 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐬𝐨 𝐦𝐮𝐜𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐡𝐲 𝐨𝐫 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭. When and where clarify the context for action beyond doubt. That’s the thinking behind this way of cue-based planning, also called 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬. They leave nothing to doubt by spelling out the time and place for a desired behavior.

𝘐 𝘸𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘥𝘰 𝘟 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦 𝘠 𝘪𝘯 𝘭𝘰𝘤𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘡.

I will meditate/write/exercise at 7am in the bedroom/study/gym.

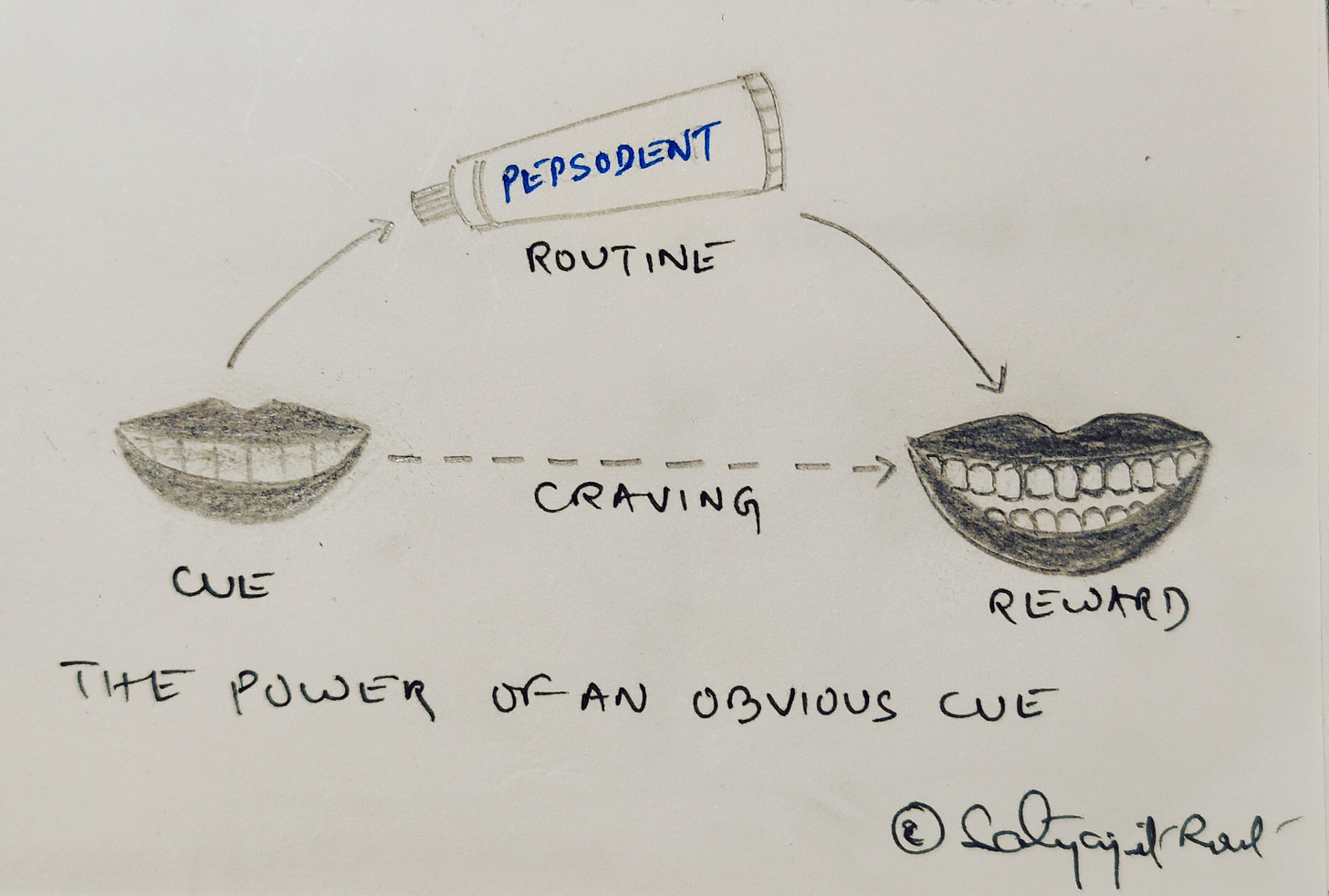

Making an implementation intention elevates the power of the cue. 𝐎𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐲𝐨𝐮’𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐭𝐬, 𝐲𝐨𝐮 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐤 𝐨𝐟 𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚 𝐧𝐞𝐰 𝐡𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐭 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐨𝐩 𝐨𝐟 𝐚𝐧 𝐞𝐱𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐡𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐭.

𝘈𝘧𝘵𝘦𝘳 [𝘊𝘶𝘳𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘏𝘢𝘣𝘪𝘵], 𝘐 𝘸𝘪𝘭𝘭 [𝘕𝘦𝘸 𝘏𝘢𝘣𝘪𝘵].

Habit stacking lowers the chances of you flaking out by bookending desired routines. The statement 𝘐’𝘭𝘭 𝘦𝘢𝘵 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘵𝘩𝘺 hangs suspended by sheer intent. It has no time or place and therefore no context attached. In contrast, consider:

𝘈𝘧𝘵𝘦𝘳 𝘐 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘬 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘭𝘶𝘯𝘤𝘩, 𝘐’𝘭𝘭 𝘥𝘰 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘶𝘴𝘩-𝘶𝘱𝘴. 𝘈𝘧𝘵𝘦𝘳 𝘥𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘱𝘶𝘴𝘩-𝘶𝘱𝘴, 𝘐’𝘭𝘭 𝘴𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘦 𝘮𝘺𝘴𝘦𝘭𝘧 𝘨𝘳𝘦𝘦𝘯𝘴 𝘣𝘦𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘐 𝘱𝘶𝘵 𝘢𝘯𝘺𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘦𝘭𝘴𝘦 𝘰𝘯 𝘮𝘺 𝘱𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘦.

All your desired behaviors are held securely within a tight structure. You are shielded from impulses.

While specific habit stacks are great for cutting down decision-making load for entire stretches of the day, 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐡𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐭 𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐬 can do the same for recurring cues. They do so by replacing 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘯 with 𝘢𝘯𝘺𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 with 𝘢𝘯𝘺𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦.

𝘈𝘯𝘺𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦/𝘈𝘯𝘺𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘐 𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘢 𝘧𝘭𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘪𝘳𝘴, 𝘐’𝘭𝘭 𝘵𝘢𝘬𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘮.

𝘈𝘯𝘺𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦/𝘈𝘯𝘺𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘐 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘢 𝘣𝘰𝘰𝘬, 𝘐’𝘭𝘭 𝘸𝘳𝘪𝘵𝘦 𝘥𝘰𝘸𝘯 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘐 𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘯.

For long we have evaluated ourselves and those around us on intentions. But the best intentions aren’t always enough and the strongest motivation wears out. What works for creating consistent routines is context. Implementation intentions lend context better than anything else.

Why pros and cons won’t work for me (or you)

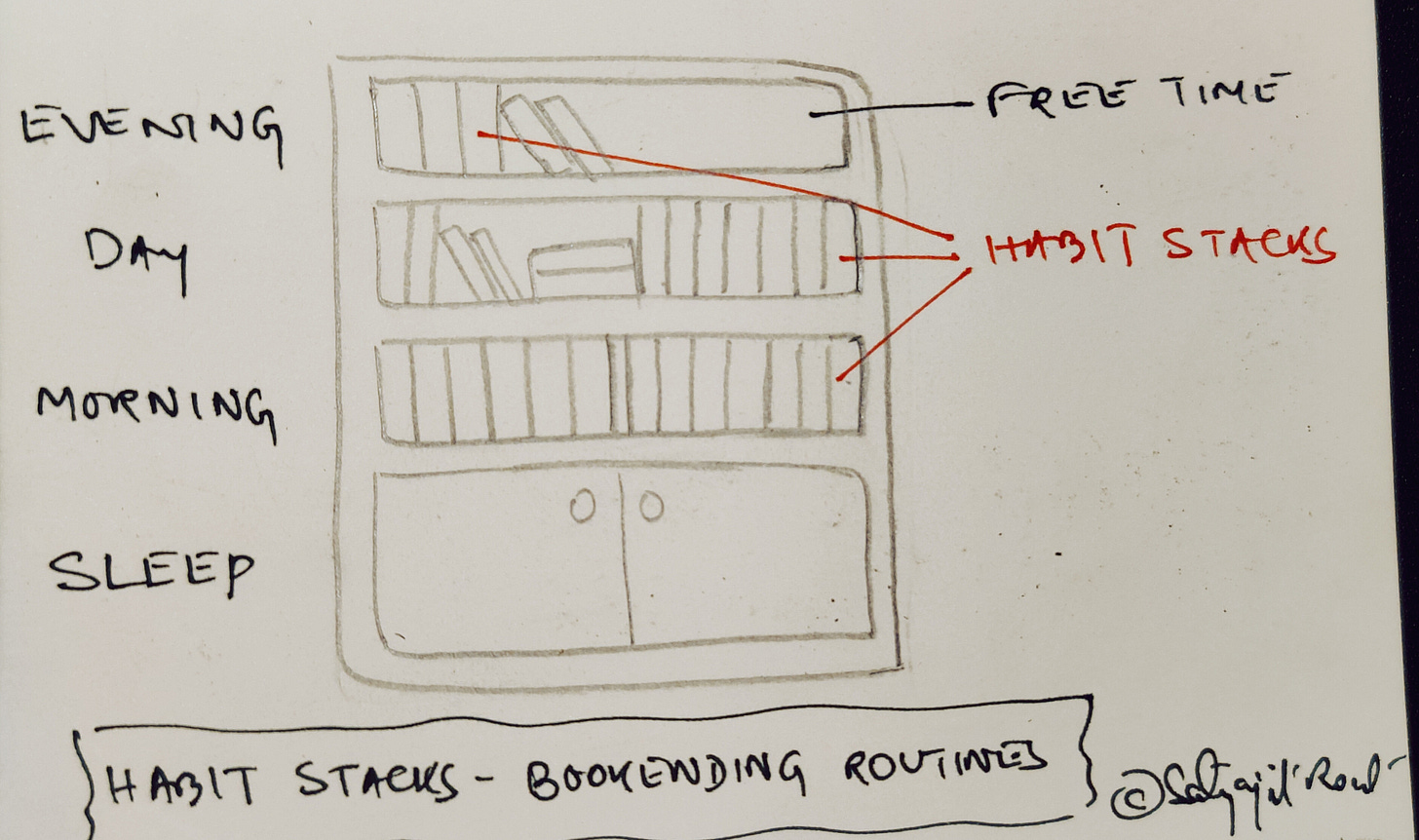

We all have unusual friends. I had a friend who was into flossing his teeth. No matter what, at the end of the day, he would pull out a piece of thread and run it between his teeth. The thing that didn’t make as much sense was that he was flexible with brushing. There would be days he would forget to brush, or just skip.

Doing pros and cons for a decision is like flossing. It has its benefits but there’s only so much there. There are better things you could do to your teeth if you thought about it.

𝐈𝐟 𝐲𝐨𝐮’𝐫𝐞 𝐨𝐧𝐥𝐲 𝐝𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬, 𝐢𝐭 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐨𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐞𝐧 𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. 𝐈𝐭 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐚 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧 𝐬𝐞𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐳𝐞𝐫𝐨.

If you’re doing the pros and cons of buying a house, for instance, it implies you’ve settled on buying a house as your only viable option. It is often a sign of narrow framing.

𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚 𝐬𝐢𝐠𝐧 𝐨𝐟 “𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐫 𝐧𝐨𝐭” 𝐝𝐞𝐜𝐢𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧-𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠.

A 2010 study of 168 organizational decisions revealed that 71% of them were “whether or not” decisions. Which means that there was only one option on the table that could be either accepted or rejected. Over the long term, less than a half of them worked out. Of the remaining 29% that considered two or more choices, more than two-thirds succeeded.

Pros and cons are not nothing. But they are inadequate. They are a sign that you’ve probably jumped on to the first thing that came to mind. Focus is not a strength when you are trying to frame a decision to be made.

You cannot turn off your biases but you can take steps to counter them. You can generate options based on weighted objectives. Just like you would not want one or two factors to rule a major life decision (consequential-irreversible), you would not want to decide without having considered all options.

𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐲𝐨𝐮 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐚 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐬-𝐚𝐧𝐝-𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞, 𝐩𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐬𝐤 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐥𝐟: 𝐇𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐈 𝐝𝐞𝐟𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐦𝐲 𝐟𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐨𝐰𝐥𝐲? 𝐎𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐲𝐨𝐮 𝐝𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭, 𝐲𝐨𝐮’𝐥𝐥 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐳𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐲 𝐛𝐞 𝐰𝐚𝐲𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐰𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐞.

Question whether-or-not decisions. Question pros and cons. You want to have alternatives, not be spared of it.

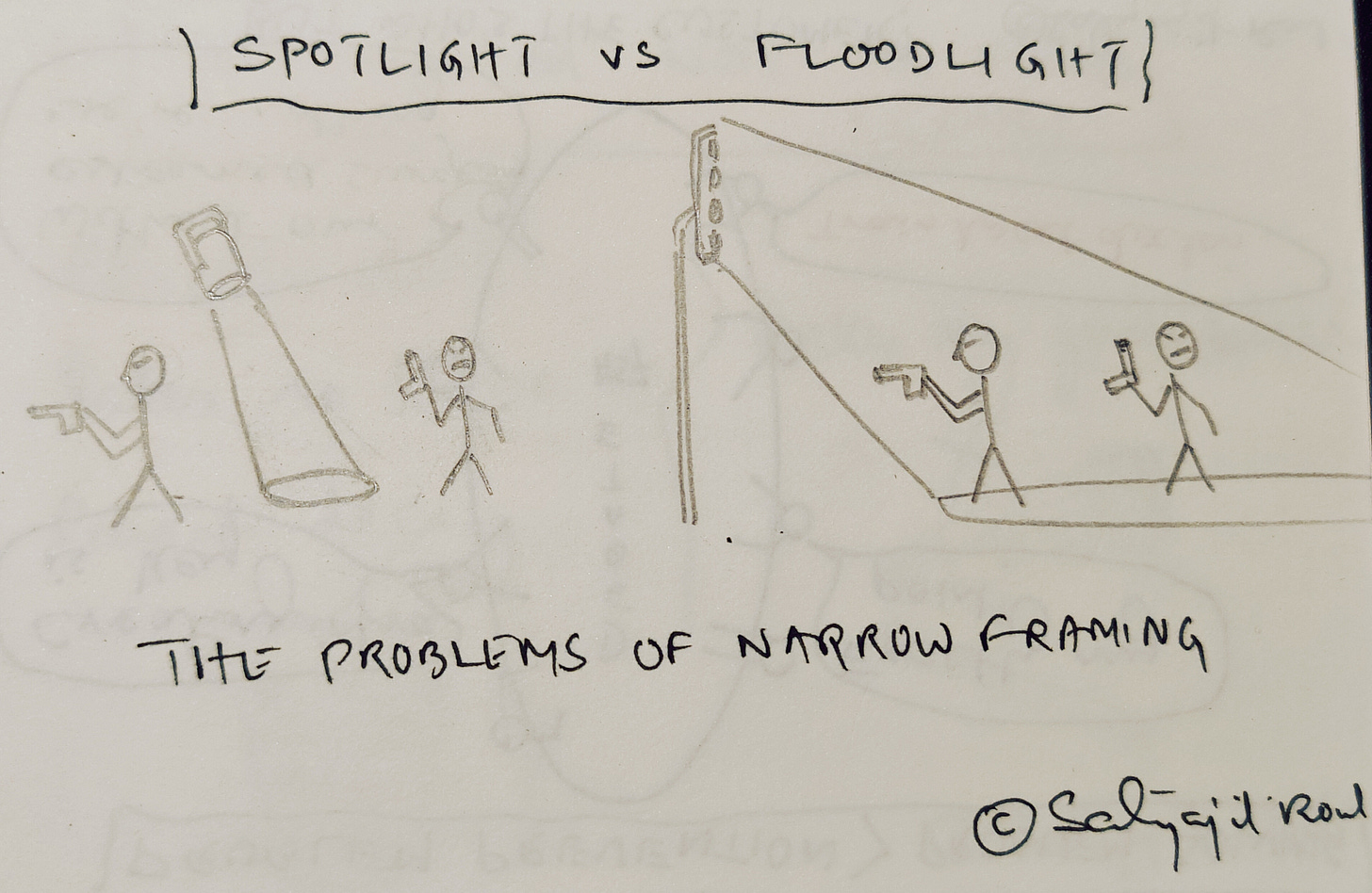

How to change your spotlight to a floodlight

A common decision-making mistake is that we sincerely believe what we see is all there is. This happens nonconsciously. Before we know it, we’ve turned on our internal spotlight and are looking hard at what it has lit up.

But a spotlight only shines a small circle on the stage. It leaves a lot more unseen. That is why I suggest that you turn on what I call your floodlights. Making a consequential-irreversible decision is like combing through a forest. You need the power of floodlights to search for clues.

How do you switch from a spotlight to a floodlight?

Dan and Chip Heath, authors of the book Decisive, suggest three ways to break out of binary thinking.

✔Vanishing Options: Say you’re torn between staying in a relationship or leaving it. Now imagine one of the two options (leaving) you’re considering is off the table. What would you do?

What could you do to make your everyday happier? How can you enjoy your partner’s company better? How can you feel more empowered?

✔This AND that: Instead of having to make an either-or decision, we could look to make a both-and decision.

For the same decision as above, assume that you’re feeling emotionally unfulfilled in your relationship. Instead of having to make a tough choice between staying or leaving right away, could you consider speaking to a friend who relates to you or join a group of like-minded members?

Parents of young children are already familiar with this. They tend to design solutions as win-win.

✔Opportunity Cost: What else could you do with the money/time/resources you’re committing?

In 1983, the CEO of Quaker acquired the parent company of Gatorade for $220mn. It was by inside accounts an impulsive buy and it led to stunning growth for Gatorade ($3bn). A decade later, the same CEO made another gut buy: Snapple for $1.8bn. That far fewer readers would know Snapple compared to Gatorade tells you how that deal turned out.

Quaker framed the decision as:

Buy Snapple

Don’t buy Snapple.

Instead of…

Buy Snapple.

Don’t buy Snapple. Keep the $1.8bn for other purchases.

Not thinking of a big decision as ‘whether or not’ means you’ve turned off your spotlight. It is the first step. You need to follow that up by turning on your floodlights and lighting up all there is to see.

We, the purpose-maximizers

Early man was a 𝐟𝐨𝐨𝐝-𝐦𝐚𝐱𝐢𝐦𝐢𝐳𝐞𝐫. Sating hunger and quenching thirst were all that mattered.

Industrialization made us 𝐰𝐞𝐚𝐥𝐭𝐡-𝐦𝐚𝐱𝐢𝐦𝐢𝐳𝐞𝐫𝐬. Working on shop floors and assembly lines were a means to that end. Most, if not all, questions stopped at: Am I being paid well enough? This is my parents’ generation. They were the last of their kind.

Today, we have become 𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐞-𝐦𝐚𝐱𝐢𝐦𝐢𝐳𝐞𝐫𝐬. Machinery has made way for computers, factories for remote work. Knowledge work is about purpose. But purpose need not be a heavy word. Purpose can be fun. It can be creative fulfilment. Kanishka Sinha writes eloquently on this.

𝐎𝐮𝐫 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧’𝐬 𝐪𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐧 𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐠𝐨 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐮𝐬𝐬𝐥𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐰𝐞𝐚𝐥𝐭𝐡 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐱𝐢𝐦𝐢𝐳𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧.

Our parents do not fully understand this, although they can guess. Our children will not understand this; they probably will live in a world where purpose is sacred.

In each of the previous ages (stone and industrial) we have believed what drives us to be X until it has no longer been true. I believe that my formal education was a remnant of the industrial age. It has little meaning today. In fact, it may be dangerous to hold on to those old textbooks. Why?

Because economics no longer looks at man as robots chasing wealth. It says that we’re predictably irrational. Marketing is about consumer psychology. Sales or any compliance work is about persuasion. We cannot expect to truly understand any of these disciplines if we do not first understand the operating system inside us. What drives us? How do we see ourselves? How do we think about what we do?

That is why I think it has become necessary for our generation to build ourselves a new toolkit. And then apply it to make decisions, build habits, learn skills, and find purpose.

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading! 🙏

Next week, we’ll get into how to identify the most important thing while making a decision. And how environment design remains one of the most under-rated drivers of behavior change, and how we can correct that.

Let me know what you made of the issue. I would be delighted to hear from you. Spread some ❤ by sharing it with a friend or two.

James Clear had something more to add to the Habit stacking concept that you have spoken about. https://jamesclear.com/temptation-bundling It's a good extension of the idea.

James Clear had shared an interesting extension of the habit stacking idea. https://jamesclear.com/temptation-bundling.