#70 - Annie Duke's outcome tail and decision dog

Plus: Anchoring effect and the toss-up between vitamin C and oranges

Hello, readers! Welcome to issue #70 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏

Readers of this newsletter may know already that there are many ways we fool ourselves when we make decisions. But that’s not where it stops. We tell ourselves palatable stories when we assess our decisions after the fact as well. Annie Duke, author of two books on decision-making, is brilliant at helping us decide with simple frameworks. Today I pick an arrow from her bow. Beyond this, we explore hiring practices and the problem of tying our thinking to a random number. Enjoy!

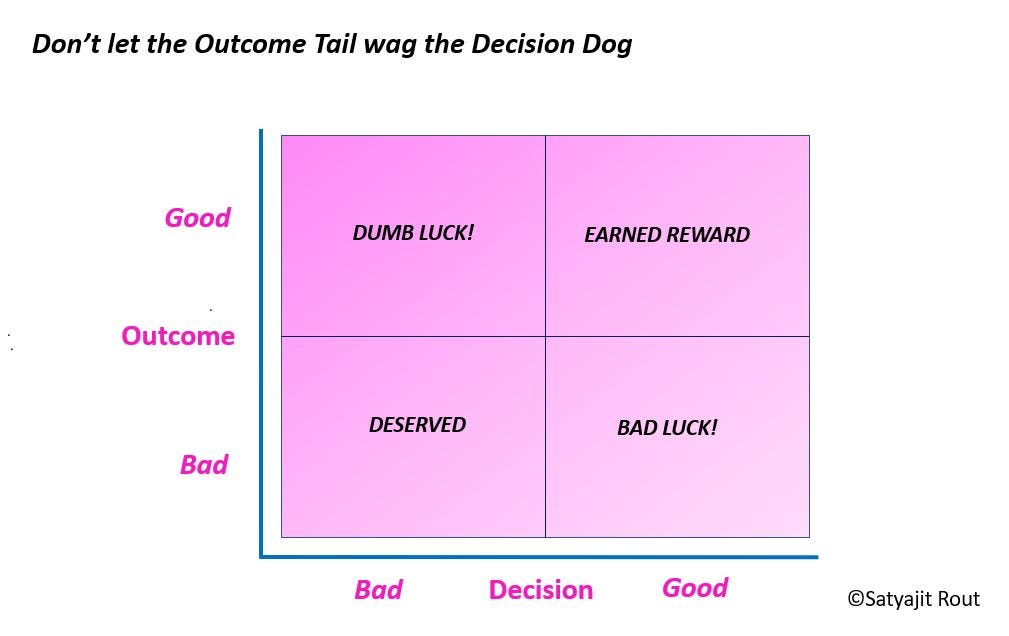

When the outcome tail wags the decision dog

One of the more common pitfalls in decision-making is linking the outcome quality to the decision quality. Annie Duke, former poker professional and decision strategist, calls it resulting. Otherwise known as outcome bias.

💡Duke calls resulting a case of the outcome tail wagging the decision dog: a good outcome is taken to be the result of a good decision; a bad outcome, the result of a poor decision.

Believing so is a problem because it is not true. Luck can get you a good outcome from a bad decision, and a bad outcome from a good decision.

A good way to snap out of a resulting mindset is to plot your decisions and outcomes over time in a 2X2 matrix.

👉If you consistently show up in the Good-Good or Bad-Bad, you may be blind to luck, which is one of two things that shape how things turn out for you. The other is the quality of your decisions.

👉If you’ve a bunch in the Bad Outcome-Good Decision quadrant, you may consider yourself unlucky and hope that the law of averages will turn the tide.

👉If you’re a frequent visitor to the Good Outcome-Bad Decision quadrant, you may want to prepare for when you run out of luck. Take a hard look at your decision-making process.

Without even knowing about this 2X2 matrix, the mistake most leaders, managers, and decision-makers make is to pay little attention to good outcomes.

Let me explain.

Picture Bad Outcome as a sad room. You’re in that room. No matter how you got in, you want to get out of there. So you search around for the door of bad luck. If you find it, you can escape from this wretched place!

Now think of Good Outcome as a happy room. No matter how you got in, you want to stay in. You don’t want to find out that you got in because of dumb luck. That’ll kill the vibe. So you stop looking for a door. You enjoy the vibe.

This is what happens in organizations. A campaign went well last year–repeat it! A product launch worked well–rinse and repeat. The last investment paid off–make another like that.

That’s why even when the music’s thumping and you’re having a blast, you must have the discipline to ask yourself: What got me here?

The Anchoring Effect

You run a small company.

Employees have a free hand. You’re championed as a leader.

Until, a sales person stays at a $500-a-night room and a designer buys a swanky monitor for $440. (Numbers are arbitrary; change them up to what’s acceptably preposterous for you.)

You step in. You set up a policy: All discretionary purchases capped at $200!

At least there won’t be any egregious expenses now, you think.

You’re right. But…

You’ve ignored the anchoring effect.

Capping at $200 eliminates larger expenses but pulls up the mean closer to the limit of $200. The policy deters serious offenders but encourages the rest to aim higher simply because it is now allowed.

We’re highly susceptible to suggestion. $200 biases our thinking to lend more weight to the anchor than is rational.

Anchoring effects are everywhere.

When your boss asks for a project completion estimate, you blurt out a random date, with the caveat that it is tentative. Until the project shoots past the date and your boss is less than happy, even though you’ve fared much better than other similar projects in the org.

You’re told during annual appraisal that the mean org-wide hike is 5% before you’re presented with your increment of 9%. Without the 5% anchor, you probably thought you deserved a lot more than 9% but now you feel a little better that you’re above average.

Anchors impose on us tunnel vision. They draw our attention to something specific during uncertainty. So we see few alternatives beyond the anchor. We may adjust the anchor until it seems plausible. But the adjustment tends to be not enough.

You don’t have to be at the receiving end of anchors. You can make them work for you too.

💡Making the first offer can be beneficial in ambiguous situations, like in a price negotiation. ‘We have budgeted X for this position’ OR ‘In the past I’ve charged Y for such projects’

💡Or you can drive up sales via arbitrary rationing. ‘Limit of 12 Maggis per person’ somehow makes shoppers a lot more than they would have without the random anchor of 12.

The best defense against anchors is to reject them as presented to you. Tell yourself and consider the full range of alternatives. Seek information that takes you away from initial impressions. That takes work but you can only get better, right?

Don’t look for oranges; look for vitamin C

As the owner of a variety store in 1954, Sam Walton made a habit of sticking his nose into other stores to see what they did well. The spying worked for Sam. It led to Walmart and things that made Walmart Walmart: central checkout line, discounting, category segmentation.

Since Walton’s time, these practices have become industry benchmarks. Today they offer no competitive edge.

Organizations and humans are naturally imitative. Imitation reduces uncertainty.

As a decision-maker in your organization, more often than not, when you track competition, you ignore the full range of choices open to you. You train your spotlight on what you see others doing.

Copy-pasting best practices worked for Sam Walton because the context across supermarket chains did not change much. But the same behavior in your industry may backfire if the context is different.

How to match context?

✔Don’t look for oranges; look for vitamin C

We are often drawn to best-in-class competitors, not best-in-class growth levers. If you can via automation drive your costs down, which competitors cannot fight you with, you should align your strategy to do more of that and less of what your opponents are doing. For that, find companies that have used automation to drive up efficiencies even if they aren’t from your core industry.

The same principle of a context match works in hiring as well.

✔Hire vitamin C, not oranges

Emily Kramer has this advice for founders and leaders looking to hire marketers: Pick those with the right business model experience. It is more important than having same-industry or same-audience experience.

With a manuscript checker my team and I were building, our model relied on outbound marketing to drive leads directly to a sales demo. We looked to pivot to a self-serve model. In the end we got a marketer without experience in self-serve and it became a case of too many firsts–it was our first time building a self-serve product and the marketer’s first time working with such a business model.

The set of marketing activities your hire has to do varies with the business model and so it’s important to put a big tick there. This hiring strategy also happens to expand your talent pool in the same way you can get vitamin C from twenty different fruits if you stop fixating on oranges.

***

Thank you for your time! If you’re intrigued by frameworks, you can get to a couple of them in previous issues here and here. If you try any of the shared strategies, I would love to know how that works out for you. And finally, let me know how I can make this newsletter more useful for you. Comments are open, so is my inbox (satyajit.07@gmail.com). Stay well!