Hello, new readers and old supporters of this free newsletter! Welcome all to issue #61 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏

On the menu today is a framework with which to create awareness about your impact at work, advice from a psychologist who studies naturalistic decision-making on how to extract the best-quality information from others, and thoughts on how one brand wins you over from another.

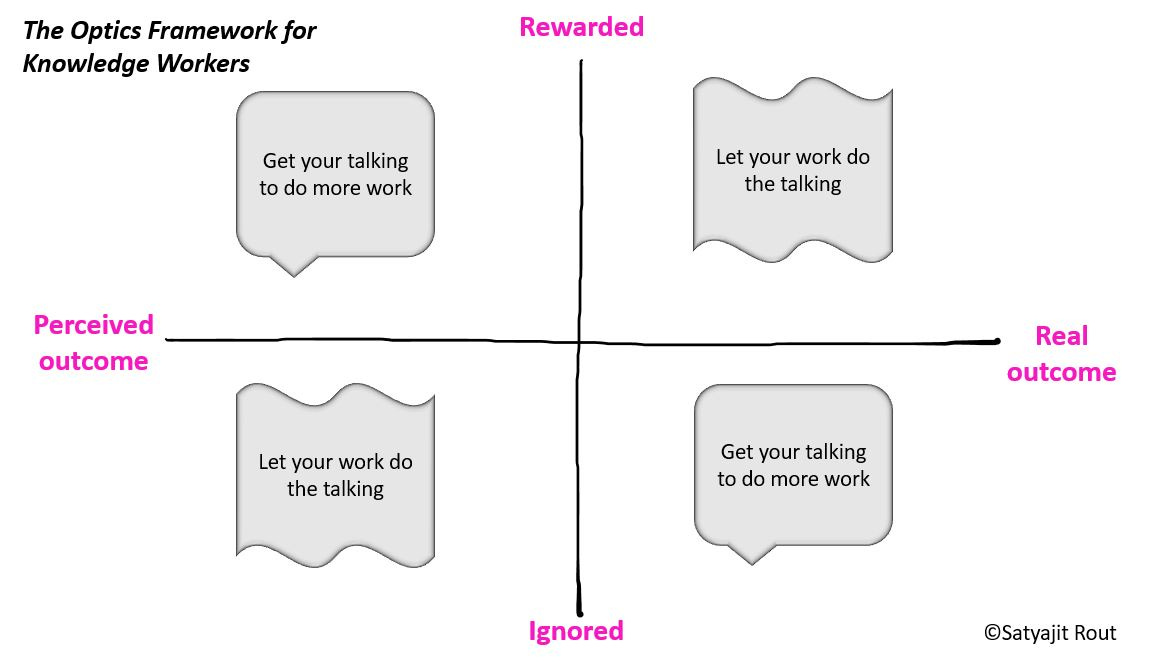

The Optics Framework (or letting your talking do the work)

As you push on with your career, how well you do depends on the awareness you create around your impact. To what extent you need to do this depends on the balance between perception and reality at your workplace.

Few realize this.

Most see themselves as thinkers or doers. The thinkers have the big ideas but find it hard to turn them into business. The doers know how to get things done if given a clear strategy. But they’re unlikely to come up with a good one themselves.

While most are in strife between their thinker and doer selves, they forget about optics. Optics is something Shreyas Doshi considers an altogether separate level of work. I can add it is especially so in a cross-functional role. So what’s the optics threshold at your workplace?

My Optics Framework for Knowledge Workers may just help you here.

Consider a 2X2 matrix where the X-axis maps distance from reality. From left to right, you move closer to reality.

The Y-axis maps distance from reward. From bottom to top, you move closer to reward.

In a firm where perceived outcomes carry more weight than actual ones, executives may turn things around by changing targets, reshuffling teams, spinning a narrative. As Will Larson, CTO of Calm and book author, writes, they end up ‘editing reality’. This is the top left and the bottom right quadrants.

Not all of this is dirty, though still harmful. Some managers can’t distinguish snake oil from the real thing–too generalist, big teams. So they look for the proxy of optics. Some, when pursuing big goals, want to fake it till they make it. But they get stuck in the faking phase.

The remaining space–the top right and bottom left quadrants–has firms that measure themselves against real outcomes. Here, perception < reality. You aren’t asked to write emails for updates given in person or random execs aren’t copied on threads or attention doesn’t vanish after launch.

Optics isn’t a bad thing. It calls upon skills that everyone should learn–tailoring your message to the audience, body language, et cetera. You also should spend extra time on management presentations and respond promptly if your CEO makes a request.

Done well, optics contributes to your brand. Things go awry when you get caught up in a hype cycle and the product (you!) doesn’t match up to the brand.

What you could do differently for more impact often relates to changing how people see you. I’m not suggesting you should give yourself an image makeover, but you should know what’s missing. And then ask if you’re willing to change perception or reality.

The Optics Framework may help you get clarity in conflict.

Changing the customer’s memory

How do we switch between brands?

How did you, a Dunkin Donuts fan, switch to Starbucks? This is a question Dan Ariely asks in his bestseller Predictably Irrational. I build on it here.

You didn’t choose Starbucks over Dunkin because Starbucks is better, even though you may say so. You did it because you were more certain Starbucks is good. This is an idea from the late Joel Raphaelson, the celebrated ad man from Ogilvy & Mather.

Deciding which is better can be a complex calculation. There’s the price, product quality, ease of access, and what the experience made you feel.

So we replace the question ‘Is this better?’ with ‘How certain am I that this is going to be good?’ And we make up a story that answers the question consistent with our past decisions. ‘I had Starbucks the last time and it was good!’ The vividness of the memory adds disproportionate weight to our decision. We trust our past self. So we line up behind our past self to make a future choice (self-herding)

Starbucks it is.

But what did Starbucks do to win you over from Dunkin in the first place?

By reframing what it offered. It didn’t just pit coffee against coffee; it introduced dimensions for which there may have been no anchor present. New coffee sizes, new choice of drinks, expensive chairs, fancier coffee machines, inviting decor, and the fellowship of other coffee lovers.

Once Starbucks was able to do that, it framed an otherwise ambiguous experience (‘Sip for sip, I’m not sure if Starbucks is better than Dunkin’) in a way that made total sense to you.

Now even when you order coffee in or take coffee to go, you pick Starbucks. Even when what you loved about Starbucks is absent (vibe, decor, service). Anchors can be sticky.

Businesses sweat over new customers because their future choices are affected by initial anchors. For any competitor, there’s a reference point, an anchor, to dislodge now.

The memory of the anchor decides customer behavior. Moving an anchor already made is hard because it is changing someone’s memory.

We don’t always make the best trades for ourselves. We don’t know how to measure our pleasure. We rely on stories, memories, and anchors. That’s why, in a free market, businesses are always working out how to provide experiences that can make sticky anchors come loose. That is how brands win trust.

Tell me about the time you changed brands. What made you?

Extracting the best second-hand information

You’ve little time in which to learn about something completely new. That information is critical to the decision at hand for you. If you’ve found yourself out of depth managing a cross-functional project or working outside our area of expertise, this is for you.

Outside your circle of competence, the most common crutch is to do as someone with direct experience says. While that may seem reasonable, it creates problems. Here are two.

People have motivations that may not match yours. If you ask your Sales head what can be done to improve conversion, they may say add more people or lower prices.

Good teachers are rare. What most specialists share with you is an exact pattern. They don’t tell you where you’re likely to trip or what lookalikes there may be. You go into the real world and look for an exact match. That can lead to what Charlie Munger calls a ‘Johnny-one-note’ situation. You’re Johnny and you can only sing one note.

So what do you do when it is not possible to learn from direct experience? When all you have is second-hand information.

Get the closest version of reality there is. How?

By asking for stories. On the The Knowledge Project podcast, here’s what cognitive psychologist Gary Klein suggests you ask:

Where did you come up with this abstraction?

What happened? Tell me what went on that changed your mind.

Why were you surprised? How did you notice it? And what sense did you make of it?

Asking these questions elicits context that a simple oral or written account won’t offer. ‘Stories,’ as Gary says, ‘are not hampered by the limitations of language, because now we have an incident account that we can drive.’

Stories have a surprise. That’s what makes them memorable. They also spawn new interpretations in the listener that the narrator didn’t think of.

When we’re learning from somebody, we’re learning their abstraction without living their experience. Seems too good a deal if you can extract everything they know without making their mistakes or spending as much time, right? And it is very much so.

As a manager or leader, you need to know enough to distinguish snake oil from the real thing. There’s a skill in extracting the most faithful abstractions from others. It needs you to get them to tell you their story by asking them the right questions. Getting better at this means you don’t have to learn everything first-hand.

Tiny Thought #5

“I think one deep mindset difference in people is often [between] those who enjoy finding the limitations of arguments and beliefs and those who don’t.” - Patrick Collison, CEO of Stripe

***

Thank you for reading! I would love to how I can make this newsletter more useful for you. Let me know in the comments or write to me at satyajit.07@gmail.com. Stay well!