#68 - How to prepare yourself to be wrong

Setting bookends, tripwires, partitions, and realistic job previews

Hello, readers! Welcome to issue #68 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏

Decision-makers spend too much time expecting things to turn out right. And too little preparing to be wrong. This is a trap. This week’s issue has four strategies to get you out of it, or even better, steer clear of it. The strategies are actionable and presented to you in a format that you’ll hopefully find easy to apply. Onward then…

Don’t be smart and predict the future. Be dumb and bookend it.

The future is a range of outcomes. When you try to predict it right, you narrow it to a single one, raising the stakes for you to hit the bull’s eye.

We often follow a high-IQ investment strategy: predict the stock price just right. A low-IQ strategy involves picking a stock whose intrinsic value is well below its current value and is therefore more likely to increase than not.

Bookending a range of values with negative and positive scenarios gives you precious margin for error. You no longer have to hit the bull’s eye to gain.

You see such bookending at play in the buying and selling of football players, for example.

Thirty-seven-year-old Cristiano Ronaldo and twenty-two-year-old Erling Haaland may both bring you the same number of goals in a season but one is a better long-term buy than the other. A top-notch striker over a career will bring you 600 goals. Ronaldo is closer to his upper bookend than Haaland is, offering a small upside and a large downside.

You can use this principle to improve your hiring practices.

💡Steph Smith, host of the a16z podcast, tweets: ‘Too many people hire talent for y-intercept instead of slope.’

If y-intercept is the present value of the hire, the slope indicates their growth curve. Often we hire based on where someone is today, not on where they are headed. Hiring someone with a lower present value (lower y-intercept) but who’s learning curve is looking up (steeper slope) gives better ROI over time.

A common mistake we can make when estimating the true value of our investments, whether in people or stock, is we go for the average. But estimating potential is not the same as estimating human height. Your ROI in early-day Facebook may be 100X your average.

A smarter way is to think of the extremes separately. Think of how bad bad can be and how good good can be. Make bets where there’s more good to be had than bad. Doing so will give you a bigger margin for error, meaning you’re likely to win even if you miss the upper bookend.

If predicting the future was hard to get right until now, it has become near impossible in today’s exponential age. Change follows the hockey-stick curve, being invisible for the most part until it is the new normal.

Predicting locks your fate to only one of several possible futures. Bookending positions you to benefit from a range of outcomes.

How are you going to bet on the future?

Set an alarm to detect smoke. You don’t want to fight a fire.

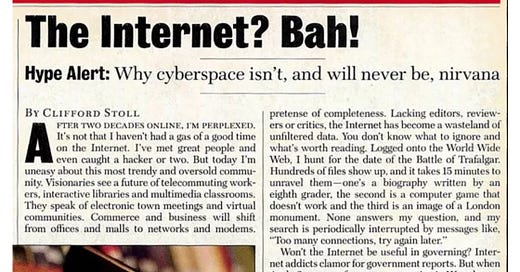

A 1981 internal Kodak report concluded that ‘the quality of prints from electronic images will not be generally acceptable to consumers as replacement for prints based on film photography’.

For the next two decades, the authors of the report could’ve been feted as soothsayers. Their forecast was dead-on. Until it wasn’t.

Between 1981 and 2001, digital technology continued to improve until there were more digital than physical cameras in the world.

What did Kodak do wrong that you and your firm can learn from?

They didn’t set a tripwire.

The book Decisive suggests that Kodak could’ve set a tripwire for action at the outset: We will act when more than 10% of the public express satisfaction with digital images.

You’re probably familiar with definitive expert views such as:

The quality of AI output in [insert name of your industry] will not be generally acceptable to consumers as a replacement for human expertise.

The quality of driving experience in electric vehicles will not be generally acceptable to consumers as a replacement for gasoline-powered cars.

The quality of viewing experience in VR will not be generally acceptable to consumers as a replacement for non-immersive viewing.

Such declarations are often accompanied by the cost barrier (Electric vehicles/VR/computation will not be cheap enough to have mass appeal).

💡They feed an anchoring bias. People’s opinions remain rooted to early-lifecycle numbers or to future blindness.

In the embryonic internet days it was believed that a mega corporation like Yahoo or ABC or AOL had to populate all the content for a world of passive consumers–a costly and risky prospect. Yet, no one company had to hire millions of staff to write the internet. We did, as active participants.

And you know who’s the customer service rep for Amazon or AirBnB? You are.

✔When technology is deflationary and change is continuous, future blindness is real. So, instead of trying to predict the future, set up a warning system to take action.

👉Set tripwires for your business: When X market touches Y number, we will act. Sometimes, X and Y may not be clear so set up periodic reviews of your position.

👉For your entrepreneurial journey: When the growth rate of an emerging trend touches Z%, I will start looking for opportunities there.

👉For your future: When more than 3 people I know find their spouse on their phone, I will set up my profile on a dating app.

(You can decide X, Y, and Z based on your level of FOMO and interest, but better make the 3-people limit non-negotiable.)

There is no one vision of the future that experts have seen and agree upon. So don’t expect to be alerted in time when the incremental becomes the unstoppable. Set a tripwire.

Partition time and money to unhook yourself from bad choices

We think we’ve self-control in spades. We think we’re not the type to throw good money after bad. Not the type to continue with something doomed just because we’ve started it.

But hand us a jar of cookies, and we plonk ourselves on the couch and wolf them down in one sitting.

This problem of autopilot isn’t limited to our cookie consumption. We lack pause more than we care to admit.

On top of that, we hate to admit failure. Especially if we’re known to be any good at what we do. Success raises the stakes for failure.

💡What we lack–and perhaps hate to admit so–is partitions. Partitions set boundaries, stopping us from slipping into autopilot. They make it possible for us to change course.

Investors don’t pump in money all at once into projects they believe in. They separate their investments across rounds and make each contingent on specific milestones being hit.

Gene Hackman tells the story of Dustin Hoffman asking him for money back when both were struggling actors in Los Angeles. Upon visiting Hoffman’s house, Hackman finds several jars labeled rent, electricity, and so on. Only the one marked food is empty. Turns out Hoffman understood the value of partitions.

How can you use partitions?

👉If a newly launched service has stalled, set a time or resource budget to prove it has got business potential. If a turnaround doesn’t arrive, drop the project. Don’t be daunted by the culture of success you see around you. They’re all faking it.

👉If you fear a relationship is going nowhere, give yourself a window to make or get a commitment. Sometimes, it’s better to quit than to persist.

👉If you happen to be around dessert after eight, don’t pick up a spoon. Stick to your rule.

Time is fungible, so is money. But they give vastly different returns depending on where you invest them. Creating partitions ensures you don’t throw good money (or time) after bad.

Partitions may remind us of failure. Or, sometimes as bad, make us examine success (what if we find it was a fluke?). But remember that they can save us from living the consequences of decisions that are past their use-by date.

It is better to be short-term wrong and long-term right than the other way round.

Why you should be vaccinated against your job

I spent a couple of hours with a life-insurance agent that left me convinced that he had been vaccinated. I didn’t check his certificate. In fact, I don’t even think such certificates exist, though they should.

For those who haven’t been through the process, applying for term insurance is notoriously painful. Agent S helped me complete the application for two term-insurance policies. He answered a hundred questions, accommodated my rising frustration, and was polite throughout.

How did he do that? My best guess is he had been vaccinated by his employer.

While hiring, employers and recruits love to sugarcoat. The result is mutual optimism arising from unrealistic expectations.

Some companies take active steps to break this illusion. They give candidates a taste of the job they’re applying for by exposing them to simulations of actual job scenarios. This practice is called a realistic job preview. It started with nurses, army and navy recruits, and life-insurance agents.

Job previews work because of a kind of vaccination effect.

💡Much like vaccines work by exposing us to a microdose of the virus, job previews succeed by exposing candidates to a small dose of on-the-job reality.

A microdose of reality gets us to start thinking about how we’ll react when the situation arises. (Or makes it clear to us that it’s better to not be in the situation altogether).

The book Decisive (I really like it!) reports the case of the company Evolv that had been hiring around 5400 people a year. After vaccinating candidates through realistic job previews, turnover dropped by more than 10% in just 12 months–a savings of $1.6m.

Realistic job previews are not easy to pull off for all manner of positions. But the idea behind them has legs, in hiring and elsewhere.

✔Changed roles recently? Ask someone who has handled the position before to show you both sides of the coin.

✔Been entrusted with a campaign launch? Ask someone who’s been there to run you through a simulation of what to expect.

Who knows in the future companies may put candidates through situational tests via some in-game experience, to test their judgment and appetite. Until then, you got to do your bit to test waters before going all in.

Misalignment in expectations is a big reason for turnover and, more recently, moonlighting. So, neither sugarcoat nor accept a sugarcoated pill. Try realistic job previews. They vaccinate you against future unhappiness.

***

Thank you for giving me your time! If you try any of the shared strategies, I would love to know how that works out for you. Let me know how I can make this newsletter more useful for you. Comments are open, so is my inbox (satyajit.07@gmail.com). Stay well!

Very interesting. I particularly liked your point on y intercept vs slope. This is why many companies have a strong campus hiring programme. The hire smart people at very low levels on the y intercept, but a massive slope potential.