#167 - Skeptical and open-minded: operating in two modes at the workplace

Welcome to another new issue of Curiosity > Certainty👋 Some quick stock-taking to make this newsletter more useful for you.

On to today’s issue…

At some point in my job, I started functioning in two modes.

This surfaced some years ago when I was helping incubate a new business unit. I would happily hear out ideas from the team I was building. I would encourage people to chip in and try and decentralize idea generation as much as possible.

Many in my team were young designers, illustrators, and content creators, and few ideas would be put to bed without being entertained first. We would talk often about and run small experiments, be it how to hack voice-overs or how to short-circuit the animation process.

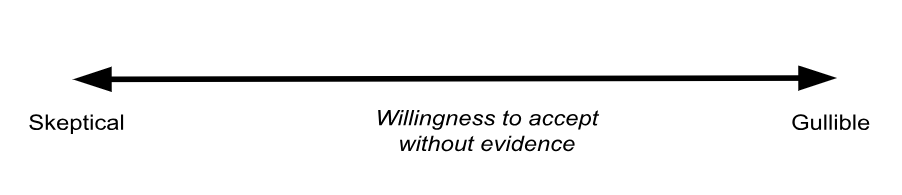

With experience, it dawned on me that not all ideas are equal. Once the price of admission for an idea drops below a threshold, people get lazy. They don’t bother to think it through. It is important here to develop good filtration skills to quickly separate signal from noise and to encourage critical thinking over mere expression.

If I showed a willingness to consider diverse ideas with my young team, elsewhere I assumed a different role. I tended to be skeptical of suggestions coming from my superiors. It could have been a change management initiative, a restructuring exercise, or some other strategic decision. I would look for holes in the argument first. I would question the validity of the evidence, or ask for more. I was the doubter in the room.

Why did I switch between being open-minded and skeptical around the two groups?

I don’t have a clear answer but this is my best guess.

I thought it was my job to play those twin roles in the company of said groups. Around a young team, I needed to be receptive first and foremost and help build their confidence, before gently nudging them in the right direction. And the results were promising. The reduction in emotional friction helped push out intellectual and ownership inertia.

Around company leadership, my thinking was, Here’s a seasoned bunch that doesn’t need confidence-building. What they need is for someone to shine light on any blind spots so that it helps make the plan better.

I assumed my superiors knew the role I was playing and gave me sanction for it, explicitly or not. I did not bother to check this assumption. It is only with time that I got a sense that my poke-all-holes approach was not working as I thought. Annual feedback suggested this. It was only much later when I sought out my ex-boss for an honest appraisal that the penny dropped for me. He conveyed that sometimes I bore the impression of being a contrarian (he used the word ‘activist’). We went on to discuss why that may have been.

Upon reflection, these are my suggestions for a skeptic’s toolkit:

1️⃣Announce the hand you’re going to play. Without priming, raising doubts can be seen as violating an unspoken social contract. Make explicit what you’re going to do before you do it. (‘These points seem well thought through. Let me do the necessary work of pushing back at a couple of places.’)

2️⃣Communicate probabilistically. Tease out the assumptions buried under sweeping pronouncements. Do so by conveying your level of confidence. Instead of saying ‘This may not be the best idea’ try saying ‘I’m 70% confident that a freemium model is the best way forward provided the underlying assumptions around the market size are valid. If however the market is much smaller, then your view may be the way to go. What do we know about the addressable market?’

3️⃣Keep your mouth shut. This takes some self-restraint, especially for those who call it as they see it. Sometimes pointing out room for trivial improvement causes a non-trivial dip in motivation for the idea owner, which leads to much poorer execution. Under such circumstances, staying silent is the best strategy.

4️⃣You can’t change people until they are ready for change. Don’t add your 5% to improve on someone else’s 95% is generally sound advice. But say the situation demands that even a 5% improvement leads to substantial gains and must not be ignored, then make sure to nudge the idea owner gently to see the wrinkle you see in their plan. Lead them to think that it was their idea all along, or else they will not own up to it as you would want them to.

Points 1—4 notwithstanding, merely being skeptical may not suffice. Offer to help out however you can so that you’re not seen as a problem inventor. If danger was not on people’s radar, and now is thanks to you, they will more often than not appreciate your offer to deal with it as long as it doesn’t seem like you’re looking to hog their share of the credit.

👋Hi, I’m Satyajit and welcome to my newsletter. I learn from the best with the goal of unpacking lessons that help make decisions for a better career and a better life.

I'll play the role of the very person you're giving advice to and ignore the advice anyway and present option 5: work with people without egos. 😆

I think what you've said here is something a lot of us can relate to.