Why 'enjoy now, pay later' is dangerous AND the problem with problem solving

Hacking the habit loop, keeping options open, and avoiding problems

In this issue:

Identity decides priorities: Any meaningful change you want to make in your life is a new identity you will assume. A transformation in your behaviour can only be auto-powered by a transformation in your identity

Understanding the habit loop: When doing something feels good, your brain remembers it and pushes you to more of it. But you don’t know that in the beginning. Every habit starts off as a treasure hunt.

Four laws of behavior change: We cop out doing the right thing more often than we’re proud of because short-term rewards seem too good to pass up. James Clear’s laws guide us when our better sense deserts us.

Keeping options open when waiting to decide: Until you have what you need to make a big decision, you would want to position yourself for a variety of futures instead of simply going with consensus.

Problem prevention > problem solving: Problem solving seems heroic. But avoiding problems can be a far better approach to decision-making than solving problems can.

Identity is the root, behavior the flower

I’ve been writing on habits for a bit, and some of you have written to me asking about strategies for habit change. I can only suggest things that I have tried. But even before that, I feel it is necessary to trace habit/behavior building back to its source.

The deeper point is this: 𝘏𝘰𝘸 𝘸𝘦 𝘴𝘦𝘦 things affects 𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘸𝘦 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭 about things and 𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘸𝘦 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭 about things shapes 𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘸𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘵.

But what decides how we see things? It is 𝐰𝐡𝐨 𝐰𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞, our identity. That is the root.

Think of the most fundamental roles you play in life: parent, child, spouse. Think of how 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐚𝐮𝐭𝐨-𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐞𝐬 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐬. It doesn’t take much willpower for you to do what is needed. You may say, Isn’t that obvious?

It is. Now imagine your life once you no longer identify yourself with a fundamental role. You have to drag yourself to drop your wife at work or take your parents to the doctor. Caring suddenly becomes ten times a burden.

Any meaningful change you want to make in your life is a new identity you will assume. You want your new behaviors to be automatic, not effortful.

𝐀 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐛𝐞𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐨𝐫 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐨𝐧𝐥𝐲 𝐛𝐞 𝐚𝐮𝐭𝐨-𝐩𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐲 𝐚 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐭𝐲.

Behavior follows identity. What you do follows who you see yourself as. If you want to consistently act a certain way without needing external motivation, be someone for whom that behavior is most natural.

Tactics and hacks reverse faster than you think. They work only after the foundation is correct. The foundation is what stands the test of time.

Identity is the root; behavior is the flower that everyone admires. You cannot plant cut flowers and hope that something grows–I’m not a botanist but I would assume this is harder.

For long-term change, you will have to replant yourself. The strategies of affirmations and fresh starts are ways to replant. But it is replanting still, not pruning or trimming. Once you accept this, you can only give yourself time and not be hard on yourself when you don’t see flowers overnight.

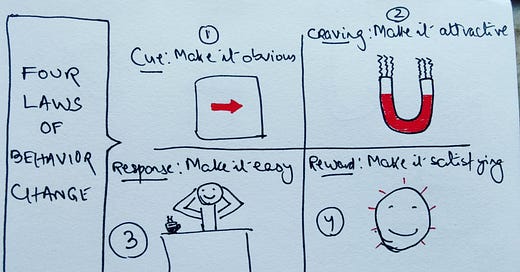

Understanding the habit loop

You now identify yourself as the person you want to be. With that as the kickstarter for the ‘New Me’ campaign, you start canvassing votes. Every action aligned with the ‘New Me’ is a vote you need. But even with the best intentions, it is easy to forget to vote. How do you stop yourself from flaking out?

𝐔𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐡𝐨𝐰 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐭 𝐥𝐨𝐨𝐩 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐤𝐬 𝐬𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐲𝐨𝐮 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐡𝐚𝐜𝐤 𝐢𝐭.

When doing something feels good, your brain remembers it and pushes you to more of it. But you don’t know that in the beginning. Every habit starts off as a treasure hunt.

𝐇𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐭 = 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐛𝐥𝐞𝐦 (𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐞) + 𝐒𝐨𝐥𝐮𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 (𝐡𝐮𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐞)

𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐛𝐥𝐞𝐦 = 𝐂𝐮𝐞 + 𝐂𝐫𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠

𝐒𝐨𝐥𝐮𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 = 𝐑𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐞 + 𝐑𝐞𝐰𝐚𝐫𝐝

Cue = an unmet need your brain spots (hunger, thirst, pleasure) for a reward (food, water, sex)

Craving = the driver to fill the need (the thing that pushes you ahead)

Cue is simply noticing. The same cue for two different people may lead to completely different desires. Once a desire surfaces, 𝘤𝘭𝘪𝘤𝘬. A program is activated in your brain. You respond to it with an action. The action brings you the reward. Your craving is satisfied. You’re happy for the moment.

Something else has also happened: 𝐚 𝐟𝐞𝐞𝐝𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤 𝐥𝐨𝐨𝐩 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝. 𝐘𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐛𝐫𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐧𝐨𝐰 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐰𝐚𝐫𝐝 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐮𝐞. It remembers the actions to get to the end, and now it wants them repeated.

This program is running non-stop. You’re continually scanning for cues, predicting the reward, taking an action, and working out if the payoff is worth it. You cannot stop the program from running. It is preset.

You may be wondering about the point of understanding a habit loop, if you can’t stop it. If you’re simply at the mercy of biology.

Biology has served us well. By making certain behaviors automatic, it has freed us to think new thoughts and look for new opportunities. Remember your first time at the airport? How complicated everything seemed. Imagine if you had to spend the same effort every time.

We can hack the habit loop by working 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 the way we are wired. Doing it any other way means we’re only fighting ourselves.

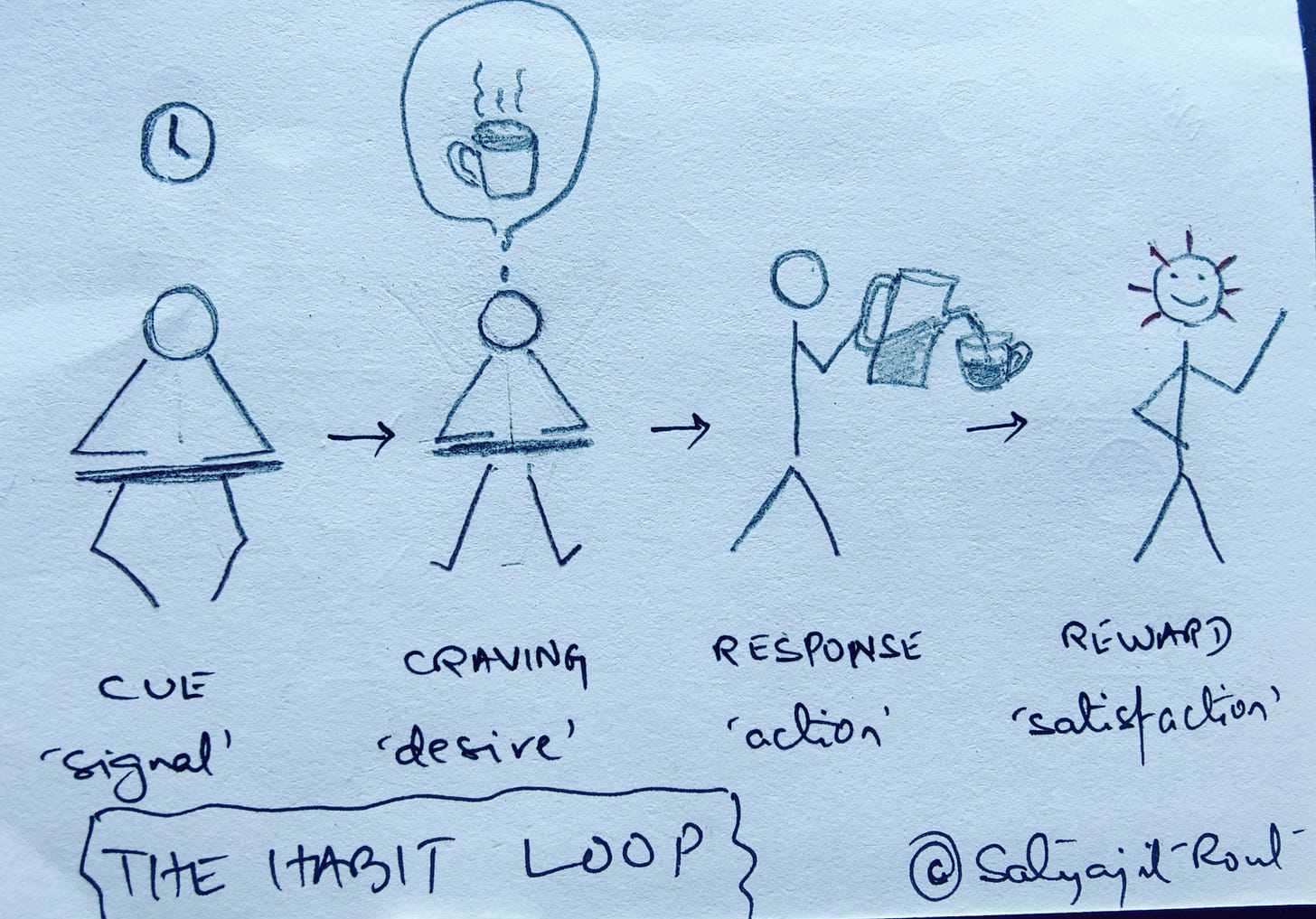

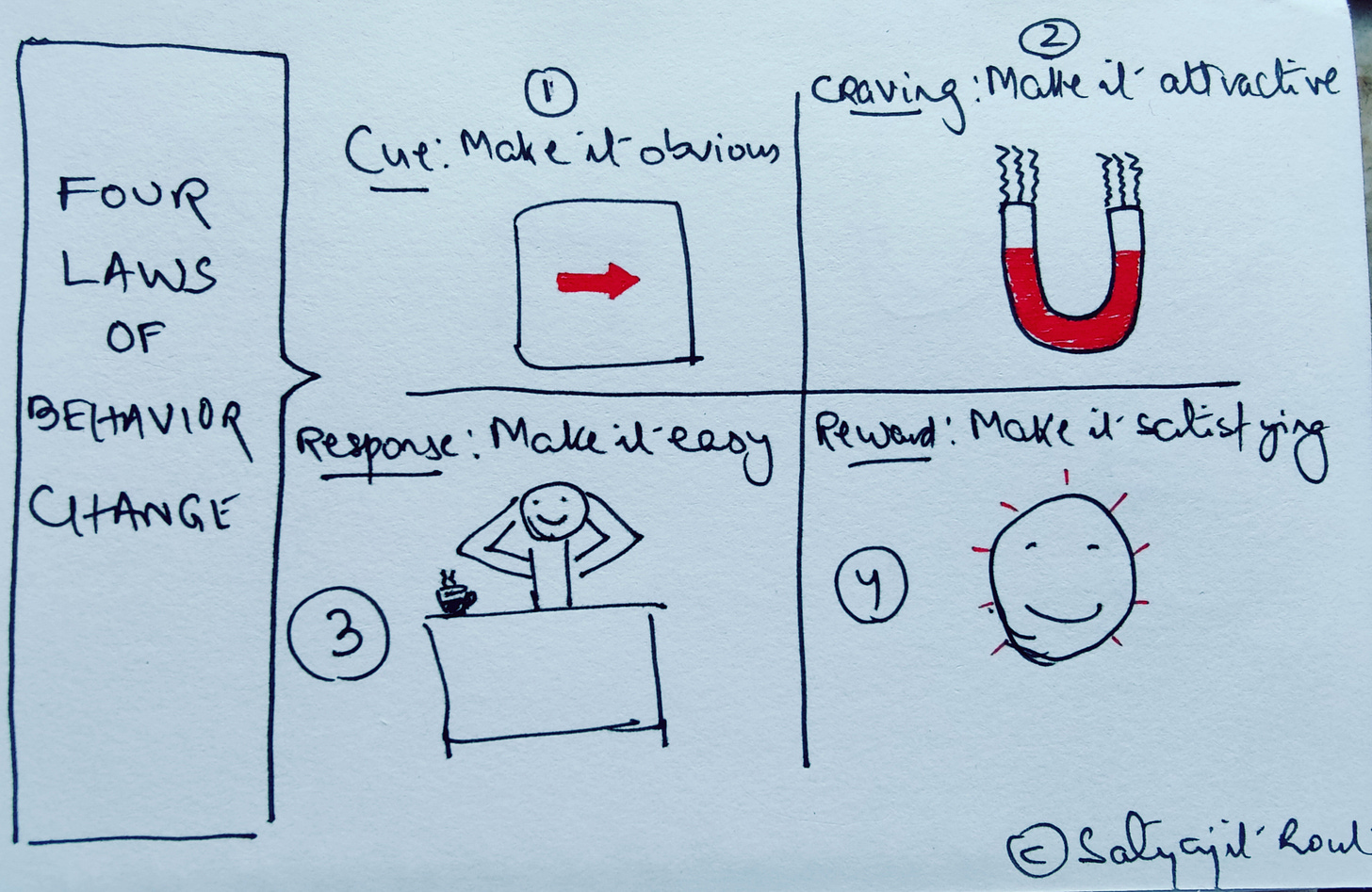

Four laws of behavior change

Every action has a cost and a benefit. You would think that you do something only if the benefit is more than the cost. But I will argue that 𝐲𝐨𝐮’𝐫𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞𝐥𝐲 𝐭𝐨 𝐝𝐨 𝐬𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠, 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐭𝐨𝐨, 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐧 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐬𝐭𝐬 𝐨𝐮𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐟𝐢𝐭𝐬. By simply having the benefits first, you can end up doing something that is of net negative value.

Think credit cards, cigarettes. Their appeal is allowing you to enjoy the benefit before incurring the cost. The sequence in which cost and benefit appear is important.

‘𝐄𝐧𝐣𝐨𝐲 𝐧𝐨𝐰, 𝐩𝐚𝐲 𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫’ 𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐧 ‘𝐩𝐚𝐲 𝐧𝐨𝐰, 𝐞𝐧𝐣𝐨𝐲 𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫’.

James Clear’s laws of behavior change address this fundamental problem of how we assess cost and benefits. He proposes four laws that reduce costs and amplify benefits for good habits, and vice-versa for bad habits.

Each law is designed to tackle a stage of the habit loop–one each for cue, craving, response, and reward. Together, these laws create a habit system that is the springboard for good habits and damper for bad ones.

Laws for building good habits:

𝐂𝐮𝐞 - 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐢𝐭 𝐨𝐛𝐯𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬

𝐂𝐫𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 - 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐢𝐭 𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞

𝐑𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐞 - 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐢𝐭 𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐲

𝐑𝐞𝐰𝐚𝐫𝐝 - 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐢𝐭 𝐬𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐬𝐟𝐲𝐢𝐧𝐠

If something’s easy to notice and presents an attractive proposition, it becomes a problem worth solving. And if there’s little friction while doing it and positive reinforcement at the end, you’re motivated to do it again.

You can then invert the same laws to break bad habits.

Cue - make it invisible

Craving - make it unattractive

Response - make it difficult

Reward - make it unsatisfying

If something’s hard to notice and is unappealing, you may not see it as a problem worth solving. And if the path to an action is littered with obstacles and walking it needs effort, you are likely to not take it.

You would think this is bringing a flamethrower to a stick fight. Isn’t just breaking one stage of the habit loop enough? Bad habits are incredibly sticky and good ones rather slippery to put together.

We cop out doing the right thing more often than we’re proud of because short-term rewards seem too good to pass up. Our path to the right thing is loaded with misdirections: impulsivity, forgetfulness, procrastination, overconfidence, to name a few.

It is clear. We need rules to guide us when our better sense deserts us.

Keeping options open when waiting to decide

We would all love to be sure of ourselves and not have to care about what the rest of the world thinks. But if we’re doing the same things as the crowd, we’ll get the same results as everyone else. That is why until you have what you need to make a big decision, you would want to position yourself for a variety of futures instead of simply going with consensus.

Here are three techniques to keep options open while you make the best choice.

✔𝐀𝐯𝐨𝐢𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐨𝐮𝐭𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭: During a particularly busy time in my life, I was desperate for a break. I squeezed into one rainy weekend a road trip with a 12-hour drive each way. Three hours in, I had totaled my new car and was stranded on the highway. 𝘛𝘰 𝘨𝘦𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘴𝘮𝘢𝘳𝘵, 𝘺𝘰𝘶’𝘷𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘰𝘴𝘴 𝘴𝘵𝘶𝘱𝘪𝘥 𝘧𝘪𝘳𝘴𝘵. Ask yourself: What’s the worst outcome here? Then take steps to avoid it.

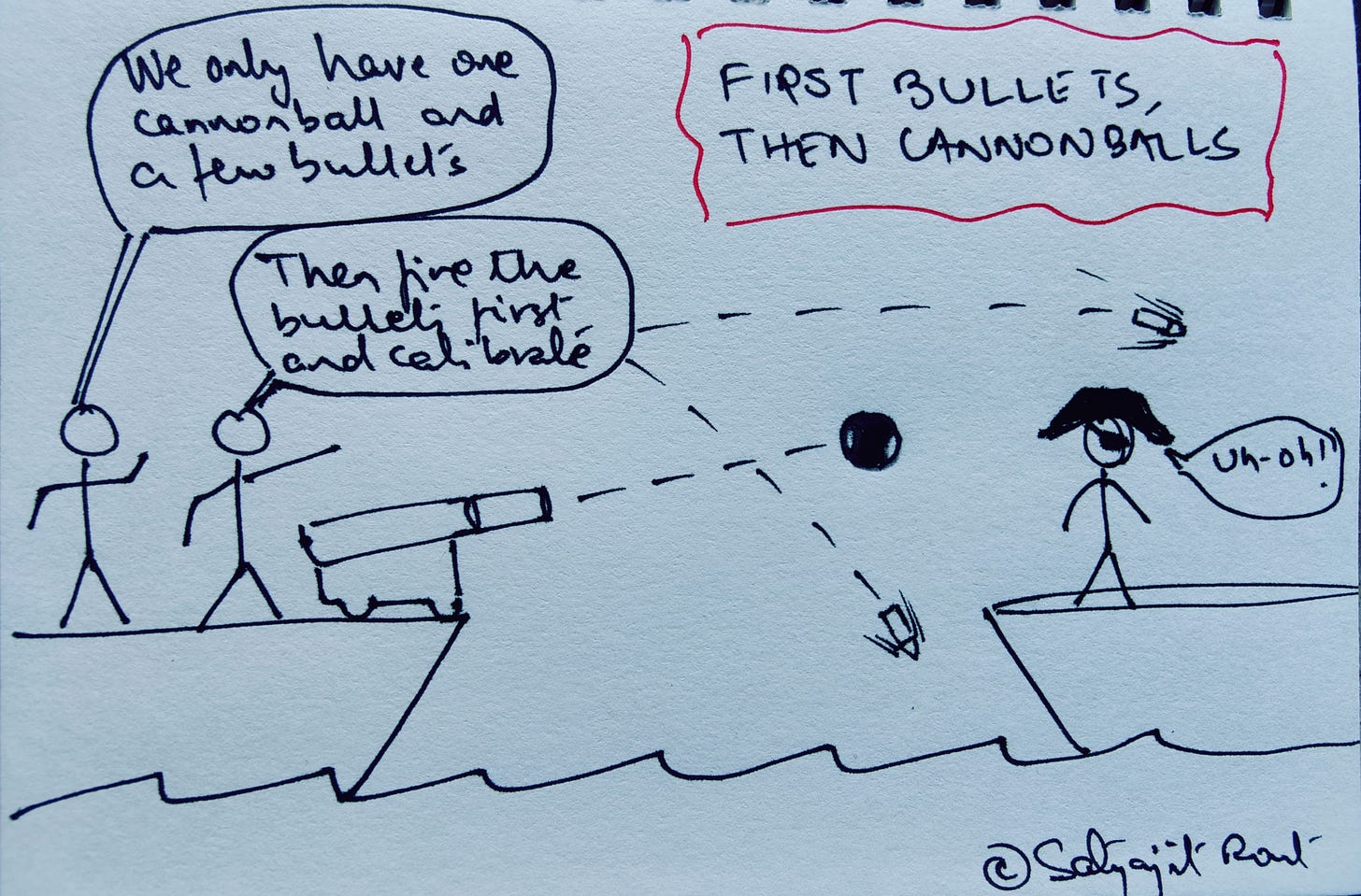

✔𝐅𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐛𝐮𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐭𝐬, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐜𝐚𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐧𝐛𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐬: This is a strategy made famous by Jim Collins. He advises running low-cost low-risk experiments that inform you about the best use for your limited resources (men, money, market). Chip and Dan Heath call it 𝐦𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐢𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠–considering multiple options at once. Multitracking has built-in fallback options (𝘪𝘧 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴, 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵).

Most decision-makers are aware of this principle. Where they miss out is the ‘at once’ bit. They run one test at a time and grow impatient, or they worry about cost. Sometimes, though, it may just be hard to generate good options to test–that’s when you need to find someone who has solved your problem.

✔𝐀𝐭𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐢𝐭𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠: Fear and worry often drive urgency. You may encounter it acutely with ‘people’ decisions. That’s when it helps to sleep over your decision, even for just a day. 𝘉𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘦 𝘰𝘯𝘤𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶’𝘷𝘦 𝘥𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘥, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘳𝘵 𝘴𝘦𝘦𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘳𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘪𝘭𝘵𝘦𝘳 𝘰𝘧 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘥𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯. Waiting before announcing allows you time to see the world through that filter.

There’s a time during the process of making a consequential-irreversible decision that tests your resolve. If you feel a certain fear waiting at the crossroads when others have chosen their paths, remember that there’s a certain solace in failing if others are failing too. In the end, you may not be all that upset about missing the mark if most others around you have missed too. A low base rate is kind to the ego. Think of that tough physics paper that baffled everyone in class.

But that’s not all you want. You want to beat the odds. On important things, you want to be right when the world is wrong. For that you’ve to be willing to be short-term wrong and long-term right.

Problem prevention > problem solving

There’s an idea that is 10X as effective but put to use only a tenth as often as another more celebrated idea. 𝐀𝐯𝐨𝐢𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐛𝐥𝐞𝐦𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐟𝐚𝐫 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐚𝐜𝐡 𝐭𝐨 𝐝𝐞𝐜𝐢𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧-𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐨𝐥𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐛𝐥𝐞𝐦𝐬.

Problem solving is fire-fighting. You come to work, life firefighters do, and rescue business objectives, like those trapped, from burning to rubble. It seems heroic; it never goes unnoticed; and it’s unmatched in urgency.

The problem is, you could be sucked into fire-fighting. Business seems to have a knack of putting itself in danger all the time and it’s your job to rescue it each time. Before you know it, you’re on a fire-fighting treadmill. The book Decisive tells a revealing tale.

In the 1990s, the non-profit Interplast did cleft-lip surgeries on children in developing nations using volunteer surgeons from developed nations. They allowed surgeons to bring family on trips and young residents to accompany surgeons as apprentices.

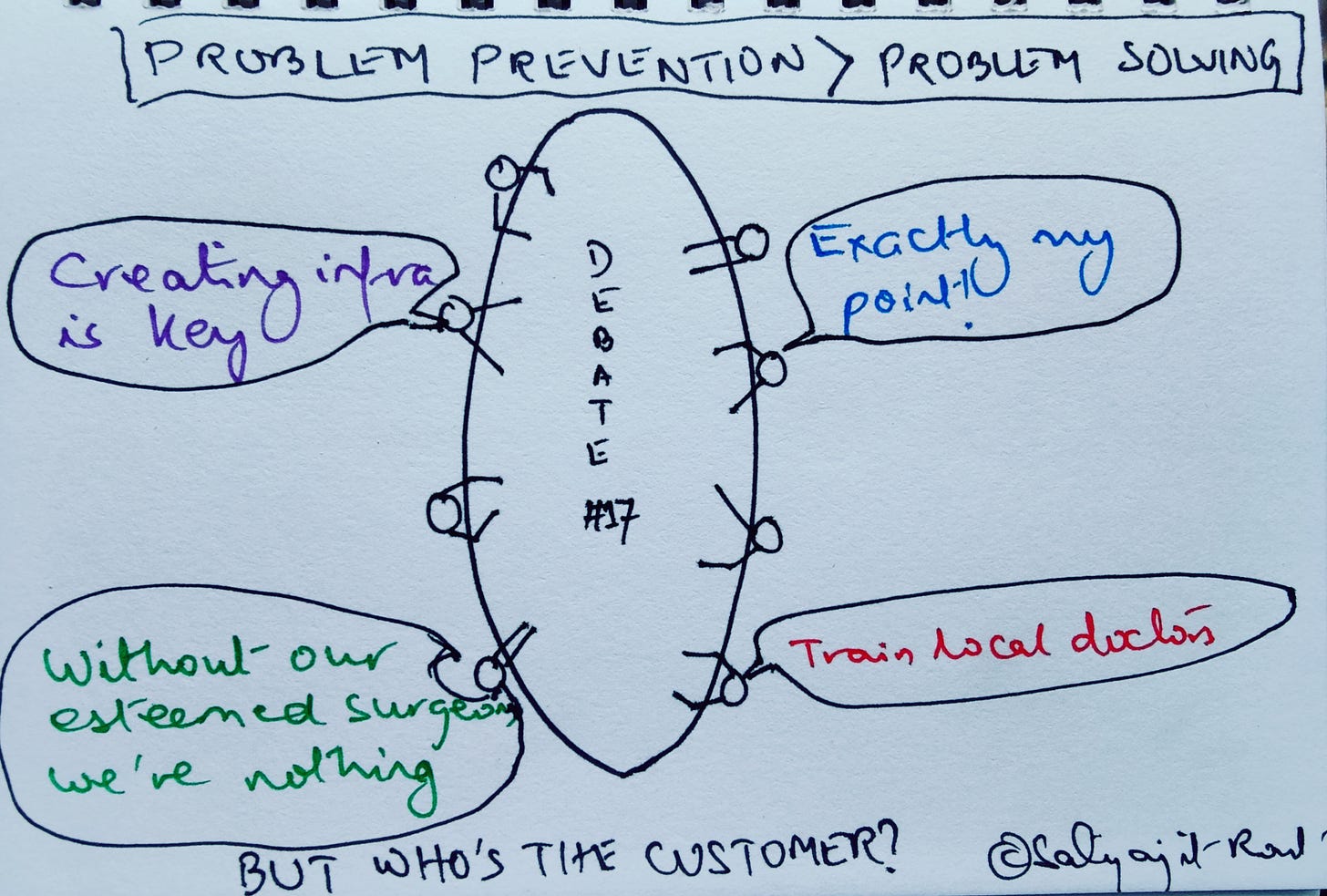

This is what split the Interplast board in two.

While these practices spurred high-profile volunteer surgeons enough to give up vacations to help poor children, it did not help set up local infrastructure or train local surgeons to perform surgeries at scale. The sacrifice of the visiting surgeons was deemed heroic. Interplast had to keep them happy as capable volunteering surgeons were hard to find. But the model itself didn’t scale. There seemed to be an unending demand for cleft-lip fixes.

Several boardroom debates later, they realized: the surgeons were not Interplast’s customers; the kids needing face surgeries were. The surgeons were a symptom; the root problem was that developing countries lacked the means to wipe out cleft lips.

Tackling symptoms more than the disease is a fairly common problem across organizations. Making a symptomatic difference is valued more than making a systemic change.

Shreyas Doshi calls it the 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐛𝐥𝐞𝐦 𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐏𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐨𝐱: 𝐀𝐧𝐲 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞𝐱 𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐳𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐳𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐛𝐥𝐞𝐦 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐧 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐛𝐥𝐞𝐦 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧.

There are several ways to work around the problem-solving epidemic. The book Decisive advises ‘enshrining core priorities’ to resolve dilemmas in organizations. Shreyas suggests rewarding problem prevention and doing premortems to anticipate and tackle problems ahead of time.

Whatever the tactic, it is vital to create a culture where problem solving does not come at the cost of problem prevention. Having to wade into raging flames like others have to step under a shower is not a badge of honor. It means something somewhere has gone wrong.

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading!

Next week, we’ll go deep into one of the most persistent problems in decision-making: narrow framing. And we’ll dive into the laws of behavior change.

PS: I’ve a bunch of stuff written that does not strictly fall into any of the buckets you read this newsletter for. If the thought of that piques you, drop a comment and I’ll drop a special midweek edition.