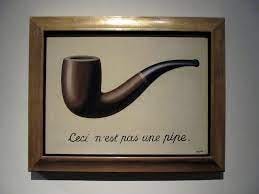

The Map Is Not the Territory: A painting of a pipe is not a pipe

Part 4 of 9 in the General Mental Models series

In 1929, French surrealist artist Rene Magritte painted a smoking pipe with the caption “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” or “This is not a pipe.” Part of a series called the Treachery of Images, the painting is both obvious and intriguing. It compels the viewer to consider an important truth: A representation of reality is not reality. A painting of a pipe is not a pipe. An image of a pipe cannot be smoked just as a river on a map cannot be waded through.

Alfred Korzybski, the Polish-American scientist and philosopher, who is credited with the expression “the map is not the territory,” points at the same basic truth. Maps are reductions of the original terrain. In Korzybski’s words, “people in general do not have access to absolute knowledge of reality, but merely possess a subset of that knowledge that is then tinted through the lenses of their own experience.” His principle inserts the observer between reality and its representation. It indicates that an abstraction of something can be read in a manner that depends on the observer. There can be as many maps as there are users, and what abstraction we refer to depends on whose map we use. But there’s only one territory.

Maps here are synonymous with abstractions of reality in any manner, form, or medium. They could be descriptions, mental models, photographs, drawings, theories. A few characteristics of maps are:

Maps are simplifications of reality; reality has many more dimensions than maps can capture

Maps are backward-looking representations (based on past data collected or experiences lived); they represent what reality looked like at the time of distillation, not what it may look like ahead

Maps don’t indicate in what aspects they are less than reality

Why is this mental model important?

This model forces us to consider the relationship between reality and its representation. The mind is creating maps of reality all the time. Since maps are easier to grasp, we are tempted to take them as ground truth. But that is fraught with danger because reality is separate from its representation in several important ways.

Consider our virtual selves. Our online persona does not necessarily correspond point by point with our true personality. This could be because we deliberately alter our persona (act of commission), we omit unflattering aspects of our lives (act of omission), or the observer erroneously interprets information about us (subjectivity).

A majority of people who interact with us online will only ever engage with this simulation of us. When large parts of our social network encounter our online avatar and come to associate it with who we are, it is an example of the map (a model of ourselves) being reverse-engineered to build the territory (our true identity). It’s bound to throw up erroneous conclusions.

The map-territory distinction is also a meta mental model in that it calls for caution against using mental models indiscriminately. Mental models help us not have to deal with every problem as if it were the first time. As we deepen our expertise in a subject, we identify patterns and start matching situations to patterns. This makes us more efficient decision-makers. However, as situations evolve in the real world, we tend to discount change in the hope of continuing to make do with the models we have already built without sacrificing speed or accuracy. We behave as if any model is better than no model. We bring a hammer to fix a headache.

And finally, even if our choice of mental model were apt, no mental model can fully explain reality just as no map can fully represent the territory it depicts. We cannot bank on a map to test how deep the waters are. We have to cross the river. In the absence of that experience–and because we have others’ accounts of the experience readily available today–it could be a costly mistake to take the world for what we want it to be (a stream that can be waded through), rather than for what it is (a body of water that can only be crossed by a bridge).

How to use this mental model?

Instead of trying to find the territory that could make the map in our heads meaningful–in other words, search for the truth that matches our preconceived beliefs–we could work with statistician George Box’s maxim that all models are wrong, but some are useful. Doing so reminds us that on the one hand, even the best models are approximations and should not be blindly followed, and on the other, that setting a threshold for allowable errors is not a compromise but a sensible safeguard.

Having come to terms with the limitations of modeling, we can now look to work within its constraints and come up with some standard operating procedures.

Get frequent reality checks: Squirreling ourselves with our maps prevents us from updating them as per reality. In the waterfall method for software development, everything happens under the hood and it is only after months that anyone finds out if what has been built is what the customer wanted, needed, or asked for. Contrast this with the agile approach of software development where engineers build a small bit of working software, let customers use it, gather feedback, and update the build.

Shorten the “Chinese whisper” chain: A user researcher talks to potential users with the objective of gaining insight into their problems. Her distillation of users’ pain points moves to a product designer who creates potential design solutions that fit the model initially created. Software developers then code as per the product requirements and ship out a product. At every stage a model of one person/group is being passed on to another. The longer the chain, the more the abstraction. Keeping this chain short, moving downstream links closer to the customer, or having precise documentation are common practices to limit information loss.

Consider the map maker. Even the most well-detailed map can be inaccurate if the mapmaker’s motives do not match the map reader’s. Where there’s misalignment in interest, it becomes necessary to adopt the perspective of the map maker and filter information based on it. A vendor is likely to expand the scope of the project if her objectives are to maximize her profits (the principal-agent problem), regardless of its utility to you. Just like the vendor, we are prone to reading situations in a manner that serves us–a trait that makes it imperative to filter information based on the map maker’s incentives.

Have multiple maps simultaneously: It’s easier to read the world in black and white, but an easier map to read is often the wrong one to go by. Think of an AA sponsor who saves you from suicide but steals your identity to bankroll her life as you recover. The best decision makers are able to hold diverse, even conflicting, perspectives simultaneously instead of seeing a complex situation along a single axis.

Open up your map to the world to build on: The most accurate maps are those shielded from the map maker’s inadequacies. One way of improving a map is to open it to external scrutiny and participation. Google Maps allows anyone to add custom data as a layer, say shark sighting locations on a stretch of beaches, and make the map more versatile.

Conclusion

The degree of correspondence we have between our representations of the world and the world itself matters. The closer our maps are to reality the easier it is to navigate the terrain. The mental apparatus we possess to understand reality is flawed. But as humans, we have the rare ability to correct our maps in accordance with our experience of reality. Upon reflection, we can notice where we’re off-base and go on to make adjustments.

Eliezer Yudkowsky said, “...A human brain is a flawed lens that can understand its own flaws—its systematic errors, its biases—and apply second-order corrections to them. This, in practice, makes the lens far more powerful. Not perfect, but far more powerful.”