How to make a habit attractive and how to lead in absence

Designing your environment, bundling temptations, and finding the most important thing

Hello friends 👏

Welcome to another edition of Curiosity > Certainty!

Last week I mentioned that I would like to have a conversation with you. So, this past week, I wrote to a few people and asked them if they would be willing to talk to me. About what exactly? About their work, their challenges, their approach to decision-making–about their problem space. I’ve had four conversations and hopefully several more to go. My early hunch is that knowledge workers’ toughest challenges are not technical. It’s not that they don’t know how to run a campaign or get the right data or upgrade enterprise hardware. These may all be difficult problems but don’t seem to be the ones keeping them up at night. What is top of mind is the sh*t no one teaches you in school.

I’m doing this experiment to challenge my idea of what a problem and solution might be. To see if people need help, or not. And if a painkiller or a band-aid is in order. If any of you are interested in being a subject in my user research, do give me a holler. I would love to chat with you.

On to this week’s issue then. We look at:

👉Designing your environment for good habits

👉Making a habit attractive

👉Making your objectives battle to find the most important one

👉Helping your team decide in your absence

And a bonus piece on how the bars for romance and convenience have moved (Hint💡: in opposite directions)

Design your environment for good habits

Between my wife and I, we have a top priority. Make the milk sipper disappear. That’s the only way for us to maintain a semblance of mealtimes for our 19-month-old toddler. The alternative is to have the day disrupted several times by the chirp of “Milk! Milk!” because of the sight of a stray milk sipper.

We all have our milk sippers. These triggers are carelessly left on the kitchen counter, on the couch, in plain sight. Once we see them, we’re nudged to take a certain action. We may not feel hungry but our hands will grab that bag of potato chips, or thirsty but we’ll chug that ginger ale. And so on.

The science behind nudging rests on what is called choice architecture. It is a fancy phrase for designing our environment in a way that pushes us toward positive outcomes. Imagine walking into a cafe and seeing salads first because they are placed at eye level. We’re much more likely to have a salad than if we had seen pastries first.

Our decisions are hugely swayed by small changes in how we see cues. Dutch designers reduced spillage in urinals at Schiphol airport by a third by painting a fly at just the right spot. All previous attempts requesting passengers to pee responsibly had met with little success.

We tend to under-appreciate the power of well-placed cues because we overestimate our self-control.

We think we are always mindful of what we need and why. So, we thoughtlessly rely on self-control instead of thoughtfully designing our environment. Yet, the fact is that we’re no better than those men who peed aimlessly for years until they had a fly to aim at.

To nudge yourself in the right direction, you need to set your default well. As a rule of thumb, the less you’re required to think before making a choice, the more likely you’re to make it.

Want to do focused work? Hop across to your neighbor and leave your phone with them. Want to limit your portion size? Serve yourself in quarter plates only. Want to save more? Make sure a portion of your income goes directly into a fund you cannot touch.

Most of us act as if we cannot choose our environment. So we act as we’re nudged by what surrounds us. But that need not be the case. We need not be victims of our environment. We can be architects of it.

How to make a habit attractive

What is common to Pepsodent, Febreze, and Dettol?

A friend of mine in undergrad was a fan of Medimix soap. He was in the minority. For the rest of us, Medimix was that bar of green soap that barely made any lather. A less foamy experience was a less clean experience. My friend labored to convince us that cleanliness had little to do with foaminess, but we were unmoved. Our Lirils and Cinthols ticked a most important box–that of feeling clean (whether or not we were, in fact, clean).

That is exactly what is common to Pepsodent, Febreze, and Dettol. Each of these brands produced a feeling that consumers found irresistible and associated with the routine of using the product. This feeling was not necessarily a sign of a better quality product, just like Medimix wasn’t perhaps an inferior soap, but it improved the perceived quality of the consumer’s experience. It made us crave something unique and then nudged us to satisfy that craving by using the product. This is what made the ritual of using them attractive to millions of consumers around the world.

We can use this insight to build healthy habits for ourselves. Create a desire for a routine by rewarding yourself at the end of it. Anticipation of that reward will drive us to take action, again and again. How can we design a craving?

Temptation bundling is the strategy of combining a habit that you want with a habit that you need. It stirs you into action by making you crave a reward you want and in the process do what you need.

You like crime fiction and you need to be fit. So you decide to listen to audiobooks ONLY when you’re out for a jog.

You like to check social media and you need to do housework. So you allow yourself social time AFTER you’ve done the dishes.

Eventually, you’ll start associating doing dishes with the rush of social media, or jogging with the thrill of a whodunit.

You can also use the principle of temptation bundling as a persuasion tool. I post at the same time most weekdays. I could call my thing Coffee with Satyajit and suggest that you pair the pleasure of having coffee (something you love) with the experience of engaging with what I put up (something I want you to love).

Marketers and sellers around us are bundling temptations with their products by creating a desire within us. We can apply the same principle to create better habits in our lives.

How to pick the most important thing

Some years ago, when my wife and I were beginning to think about homeownership, we spoke with recent homeowner friends. On one such visit, we marveled at the surrounding greenery (Sanjay Gandhi National Park in Mumbai). Our friend said that their decision to buy that place was based on a specific need. He said, “We knew what’s outside the walls was outside our control, and what’s inside we could fix. So we picked a location that was going to stay green.”

Hearing our friends made my wife and I realize we had to be clear about what was most important to us.

Not knowing what’s most important to you can cause you future regret. It can have you optimize along the wrong direction. How do you know your North Star?

Each of us has multiple objectives guiding us so taking them all into account is a necessary first step. Most objectives aren’t absolute. They have an “as long as…” attached to them. I want good pay as long as I’ve flexible hours so that I can be there for my young family. But these contingencies may not all be immediately apparent.

The process of listing down all your objectives and pitting them against each other two at a time eventually brings out what you value most. Farnam Street offers a simple way. For a big decision you’re considering:

On a post-it write one thing that’s important to you. Do this for all objectives, and you should end up with a bunch of post-its.

Stick the one you think is the most important objective on the wall.

Take another and stick it alongside.

Now ask: If I could have only one of these two, what would it be?

Along the way, add weights to the objectives.

Quick tip I learned from Jehad Affoneh: Imagine you’ve $10 to spend on your objectives and you can spend in $1 increments, how would you do it?

Continue with the post-it battles until you’ve the most important thing.

Probing what’s important to you is an exercise in self-awareness. It clarifies where you want to go and, later on, what trade-offs you’re okay making. It forces you to ask questions of yourself that you may have taken for granted. It is a practice that travels well across parts of your life: work, relationships, values.

How to help your team decide in your absence

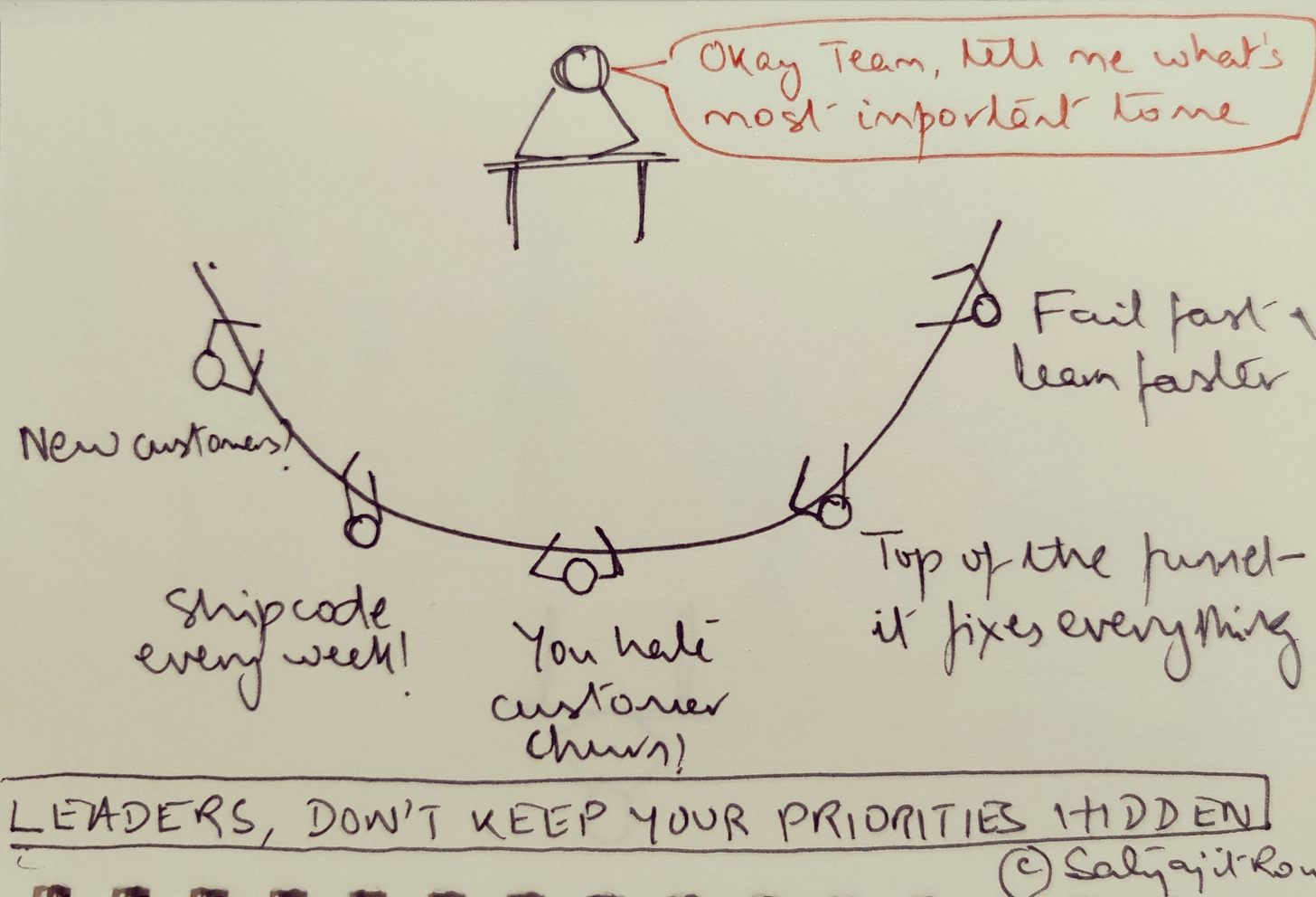

This is a situation new managers may identify with. You have a young team that you trust but you’re worried about their decision-making. You find yourself having to intervene every now and then and nudge them in the right direction. While with time your team seems to follow you better, you’re still not sure if they’re on the same page.

The worst thing you could do in such a situation is expect your team to read your mind. Even if your team does it once, there’s no guarantee they’ll get it right consistently. Perhaps a shade better, or maybe as bad, on your part is to wait for your team to ask you about what you care about.

💡Tip (if you’re a reportee): Julie Zhou suggests some ways to better understand what your boss wants. Ask your boss “What does success look like for you?" / "How do you hope things go?" or ask your peers "What do you think X cares about?"

As a leader, clarifying what’s most important to you can empower your team. Once you share what success looks like to you, you may be surprised by how swiftly your team aligns itself to your priorities. At once they feel clear about what they will be judged on and that helps them deliver much better results.

In situations where external uncertainty makes a rethink necessary, you could clarify the “as long as….” We will continue running experiments and betting as long as we’re learning something new and useful about the market.

It is not uncommon for young conscientious managers to want to leave nothing to chance. They may feel the urge to always be present. End up spending their weekends on email and chat. This may appear to the team as micromanagement, and no one would be happier for the experience. These are all symptoms of the same root problem.

Shane Parrish strikes at the heart of it: If you don’t articulate the most important thing, people are left guessing about what matters. And because they’re guessing, they need you.

If you want your team to perform to your standards, be clear about what you want from them. Once you do that, you can gradually make your position redundant. That’s the mark of a good leader.

Bonus: The moving bars for romance and convenience

When it first came out, Google’s autosuggest feature delighted its users. It bordered on magic. Today it is par for the course. We expect the search box to read our mind.

And why just Google? We expect to be pampered wherever we go, whatever we do.

GPS tracking, 1-click payment, single sign-on, same-day delivery–hard to remember that these conveniences were once privileges, or simply absent. What was delightful yesterday is commonplace today. And what is delightful today will be ordinary tomorrow.

This phenomenon is called liquid expectations.

It means that no one needs to set standards for user experience. It happens automatically. We peg our expectations to the most friction-less experience.

While the bar for convenience has climbed, that for romance has sunk.

Esther Perel, leading couples psychotherapist, calls romance anything that goes beyond the bare minimum. It isn’t a modern definition. It has always been like this. It’s just that the bare minimum has slipped.

For the boomers, trying the girlfriend’s number for hours was dating tax. You rung up, her dad answered, you hung up, you waited a wink, you rung up again.

Millennials called. On the cellphone.

Zoomers text.

The act of making ourselves vulnerable lent meaning to our actions. But if we never have to be vulnerable, are our actions robbed of intent? If courtship is without chase, does rejection matter less?

Nothing romantic has ever been convenient. That’s the whole point of it–wondering, not knowing, figuring. Romance is uncertainty.

When we raise the bar for convenience, we lower the one for romance.

Yet, I hope this is only half a truth. There’s something more that proves romance today shows itself in newer ways. What do you think?

*****

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading!

Next week, I’ll explore the seen and the unseen–or the power of looking beyond first-order consequences. And continue the exploration into habit-building from a pop-neuroscience angle.

Let me know what you made of the issue. I would be delighted to hear from you. Spread some ❤ by sharing it with a friend or two.