Hello 👋 and welcome to another Friday edition of this newsletter.

📢A few of you have received a request for feedback from me. This is me nudging you to give me two minutes to let me know about your experience with this newsletter.

Last week, a dear reader texted me the a ChatGPT-powered summary of the issue. I thought let’s give this a shot. Here’s what you’ll get in this issue:

Introduction to the concept: The article discusses the idea of deliberately making mistakes to challenge conventional wisdom and expand the understanding of sense, emphasizing the importance of this practice in decision-making.

Distinction from routine decision-making: Making deliberate mistakes stands apart from routine decision-making processes and involves questioning fundamental beliefs and assumptions.

Conditions for purposeful mistakes: Deliberate mistakes are advocated when there is a substantial potential benefit (high upside) relative to the cost (small downside). This approach is suitable for repeated decisions, non-formulaic problems, changing business conditions, and situations where familiarity with the problem is limited.

Steps to purposeful mistakes: The article outlines steps for making purposeful mistakes, including identifying critical assumptions, ranking them based on suitability criteria, designing the mistake, implementing it, and learning from the process.

Analogy with seatbelt and barbell strategy: The article uses the analogy of managing risks similar to wearing a seatbelt in a car, balancing the low risk of car failure with the high risk of seatbelt failure. It introduces the concept of the barbell strategy, which involves balancing safe, obvious choices with risky, non-obvious ones.

Conclusion on minimizing regret: The conclusion emphasizes the importance of learning from mistakes and exposing faulty assumptions to minimize regret, acknowledging that deliberately making errors of commission can lead to valuable insights and knowledge.

Example of learning through experimentation: The article ends with an analogy, suggesting that experimenting and making mistakes can be a fast and effective way to learn, even if it involves unconventional or risky actions like sticking forks in electrical sockets to understand electricity.

Thank you, ChatGPT. You’re pretty much there. Now let’s dive in.

When we say something doesn’t make sense, we always question the ‘something’, never the meaning of sense. The practice of making deliberate mistakes expands the meaning of sense by suggesting to us that putting conventional wisdom to test can be sensible.

From the outside, the practice of making deliberate mistakes may seem like nothing short of madness. You’re going against the wisdom of the crowd with low odds of being proven right. You expect to fail. But indulge your curiosity and you may find a method to the madness. Orchestrating mistakes that test fundamental beliefs at manageable cost and for a high pay-off is a net positive.

Two issues ago, we explored the concept of expected value—the net payoff in terms of upside or downside of a choice. Last week had us picking at risk. We concluded that some kinds of risk are better than others. We also worked out how to make your own luck when the odds are long. In this final part, we propose the idea of reality-testing our most cherished beliefs by—wait for it!—deliberately going against them. Making deliberate mistakes is an extreme practice of disconfirming behavior, and one I make a case for in this piece.

Clearly, the value in wilfully taking the wrong road is not clear as crystal. If it were, I wouldn’t be wasting my breath on this piece. So, where is it that the weight of opinion does not stand up to the weight of the evidence for it? Let me play the devil’s advocate and argue against the need to make mistakes to learn.

Companies are designed to chase efficiency. They are divided by function and each function is run by experts in the domain. These experts are continually optimizing for output, improving efficiency, and executing without error. All of this happens with the cushion of collective wisdom at hand where people can correct each other’s false assumptions.

So far, so good. Most organizations run as per this template. Why on earth should we disturb this status quo? End of story. Go find something better to do.

But then every startup is born out of an untested assumption. In 1946, this chain of stores called 7-eleven came about. They were open 16 hours a day, seven days a week and would run that way for 36 years before switching to a 24-hour model. What made them take the plunge after 36 years? An accident!

…following a football game at the University of Texas, customers flooded the 7-Eleven in Austin. “It couldn’t close,” notes the company’s website. The store stayed open all night. So successful was the inadvertent model that always-open 7-Elevens began to crop up intentionally; the first all-night outpost, perhaps unsurprisingly, was in Las Vegas.

This is not isolated. From science to business, stories of brilliant mistakes teach us the same lesson. They tell us that in none of the cases it would have made sense to do what led to the eventual breakthrough. Keeping your 7-eleven outlet open round the clock would have been a hard sell to the bosses because shutting shop at the regular hour was working just fine and keeping it open through the night would have meant paying for electricity and labor without any guarantee of additional business.

You can wait / hope for one of these happy accidents to come visiting. Or you can learn to orchestrate deliberate mistakes—choices made whose expected value is negative.

That’s exactly the argument I’ll make here.

When should you choose to make mistakes?

If the chase for efficiency is in the right direction. If there’s deep familiarity with the kind of challenges you’ve to deal with along the way. If there’s stability in the environment / market. If the beliefs on which you’ve based your business are rock solid. If these are true, you would be cavalier in purposely making mistakes.

By the way, all of this is the definition of business as usual. It is where conventional wisdom comes from. But if any of those attributes were to change, it would no longer be wisdom. It would be garbage, only worse because people would still be betting their livelihoods on it.

Here are some ingredients that call for something other than conventional wisdom. When these ingredients are in place, it is a good time to go against the company recipe.

1️⃣When there’s a big upside, small downside

If you volunteer to make a mistake that will kill you if it goes wrong, then you will, in all probability, die. But if you want to survive the consequences of the mistake and live to make something of the lessons learned, the potential benefit of the experiment (mistake) relative to the cost has to be high.

2️⃣When you make this decision repeatedly

One-time or rare decisions are highly consequential and have little precedence. The stakes here are so high that you’re better placed learning from others’ mistakes (check out base rate in part 1), instead of making your own. Picking such decisions to bungle up also goes against the cost-benefit ratio requirement of #1.

Repeated decisions where a correction in core assumptions is likely to bring dividends are ripe for error-making. Hiring, pricing, and sales are some disciplines where periodic rejigging of approach can unlock new insights.

3️⃣When the problem is not formulaic

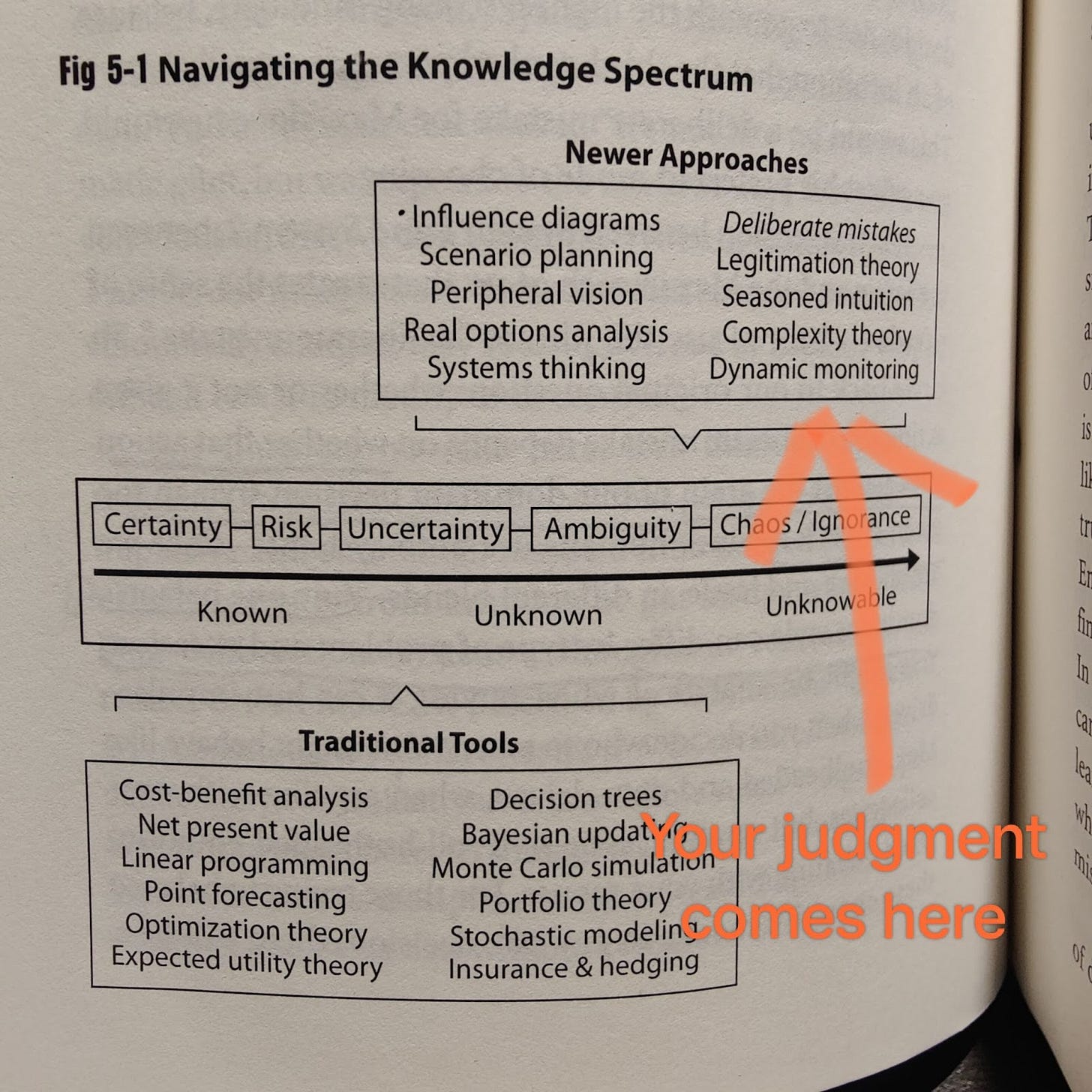

Executives are rarely paid big bucks to solve problems on a spreadsheet, like any/most of the problems to the left of the diagram above. It is the ones to the right that need creativity and judgment, that are hard to outsource to algorithms.

Imagine you’re the COO of an ecommerce logistics firm. You provide delivery to big ecommerce players like Flipkart. How do you build capacity in a way that lines up with volatile daily order volumes? While the men’s cricket world cup happens across India, how do you know a busy day (India losing?) from a quiet one (India winning?)?

4️⃣When business conditions are changing

Here’s a true story. Shopify was 600-odd, without a lease for their office, and without a new office ready. Temporarily, Tobias Lutke decided to ask all employees to work from home.

So we closed our office, as in, we deprogrammed everyone’s fob one day, sent an email the evening before, and said, “Hey, we’re going to be homeless for a month, and if anyone has some good ideas about how to deal with that, please share.” And it was pretty chaotic.

This forced work-from-home experiment turned out well enough for Shopify when Covid hit the world.

5️⃣When your familiarity with the problem is limited

Sometimes, you have done things one way and have little to no experience doing it any other way. The assumption behind your choice has not been tested because there’s no counterfactual body of experience.

As groundwork for this piece, I asked some friends to name a type of repeated decisions they made at work where the assumptions were not as tested as they should be given the frequency of those decisions. I got a bunch of interesting responses: a friend in retail sales who always asked his teams to prioritize customer service over conversion; a marketer who believed print ads have a low ROI without putting the idea to test; and a middle manager who has only ever invested himself in upward but not lateral stakeholder management

Each of these cases offers fertile ground for running tests with a low downside and high upside.

How to make mistakes with purpose

In the book Brilliant Mistakes, Paul J. Schoemaker shares an algorithm for going against company policy in five steps. He uses his own experience of challenging the most deeply held and consequential assumptions in DSI, the management consulting firm he had founded.

1️⃣Identify (the most important) assumptions to test

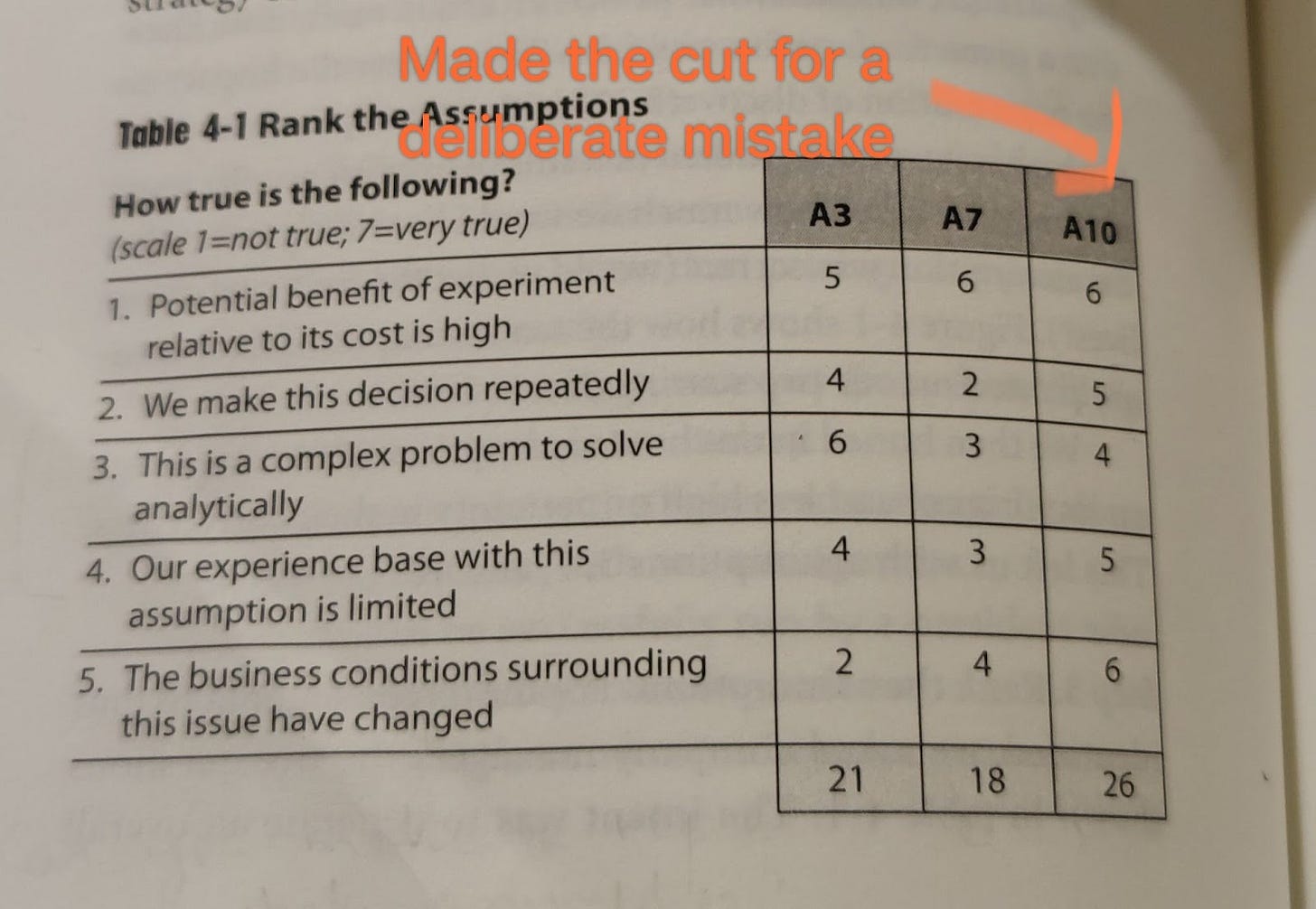

The firm’s leaders laid down the most beloved assumptions about how best to run their consulting business. This produced a list of ten while focusing on beliefs that lie at the core of the business. One way to extract these is to think of your business by function—strategy, marketing, operations, etc.

After making the list of ten, they shot it down to three to capture the ones they were least confident about but those, if proven wrong, would make the biggest difference to the business.

2️⃣Rank suitability of assumptions on the five criteria shared earlier

The participants then ranked each of the three assumptions as per the suitability criteria shared earlier and chose the one with the highest score. Now they were ready to go against company policy.

3️⃣Design the mistake

The firms’ policy had been to never respond to an RFP because of a belief that the kind of clients who use them are ‘usually price shopping or looking for options to reject a choice already made.’ The firm decided to correct this by responding to the next RFP. They managed the costs of the mistake by asking recent hires to flesh out the initial draft of the proposal.

4️⃣Make the mistake

‘Our firm,’ writes Schoemaker, ‘produced a customized response to the RFP, listing the partners’ normal fees, resulting in a budget of about $200,000 for this relatively small consulting project.’ To the firm’s surprise, the client invited them over for a visit with their management and it led to not just the sealing of the deal but also additional projects in the pipeline amounting to $1 million.

5️⃣Learn from the process

The point of the above five steps is to pick out meaningful areas of business where expectations diverge from reality. When it works out well, it unlocks outsized opportunity, as in the case of Schoemaker’s consulting firm. When it doesn’t, it doesn’t lead to ruin.

Hello, car! Meet the seatbelt.

Think of the car and the seat belt. Most of the time, you're expecting the car to work (thank heavens!). That is, to safely take you from point A to B. And every single time, you're expecting the seat belt to not come into use at all.

When you're wearing a seat belt in your car, you’re managing a portfolio of risks. The low risk of failure of the car with the high risk of failure of the seat belt. The two have negative covariance.

If the car comes good, the risk of a useless seat belt materializes. You’ve paid for something useless. You’ve wasted that money. But if the car fails (or you fail as driver), the investment in the seat belt has paid off. You couldn’t have gotten a higher return (your life) for the price of that seat belt.

In finance, covariance indicates how the returns of two assets are related. A positive covariance means both move together in the same direction. A negative covariance means the returns move in opposite directions—that’s your car and seatbelt.

I’ll make the mistake of throwing another term at you. You’ll get this one. It’s called the barbell strategy. It maintains that we should take actions that protect our downside risk while maximizing our upside potential.

Making deliberate mistakes is an example of implementing the barbell strategy. Instead of going with conventional wisdom (work from office, anyone?) all the time, pair the safety of the obvious with the risk of the non-obvious. Keep yourself safe for peacetime by covering your bases but also prepare for wartime by committing to risky investments when it’s an option, not a compulsion.

Conclusion

Regret is real. Ask anyone who’s out of the game today and they’re likely to say that they wished they had made more mistakes. One way to minimize regret is to make more errors of commission. To do that, you gotta learn the art of exposing faulty assumptions. Learn it well because the era of decades-long businesses are behind us and purposely going down the wrong path is not welcome. You will at various points have to find your own temptation to not waste time and money on doomed experiments.

Sticking forks in electrical sockets is stupid. But if you don’t know this thing called electricity and you want to know how it works, there could not be a faster, surer way for you to find that out. That’s getting better by goofing up.