Circle of Competence: A little learning is a dangerous thing

Part 2 of 9 in the General Mental Models series

This is the second piece in a nine-part series on General Mental Models. The first piece can be read here.

En route to an interview for admission into a business school, a friend had wished me “Be yourself.” Since, I’ve heard the same advice many times over and have thought about it often.

The advice to be oneself hides an important supposition. Being ourselves presumes knowing who we are or what we are good at. It overrides the possibility that we may be in the habit of overestimating our abilities on any matter of importance, which in turn begs the question: should we continue to be that person?

One pesky consequence of our amplified self-assessment is that we may find ourselves straying into uncharted territory without knowing so. At the heart of it is a failure to recognize one’s limits. The problem is one of awareness, not skills. This is a systemic glitch in us documented in behavioral psychology. A landmark paper by Dunning and Kruger (2003) states that “...people base their perceptions of performance, in part, on their preconceived notions about their skills. Because these notions often do not correlate with objective performance, they can lead people to make judgments about their performance that have little to do with actual accomplishment.”

When it comes to self-appraisal we are our most forgiving critics. This is not to be confused with how we do self-appraisals for performance management at work--a process that is influenced not insubstantially by the possibility that we may not want to appear cocky to our supervisor or may be held back by the idea of a disagreement in the assessment.

What is the circle of competence?

The origins for the mental model of a circle of competence can be traced back to the 1996 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter from Warren Buffet. In it he offers the following counsel: “You don’t have to be an expert on every company, or even many. You only have to be able to evaluate companies within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.”

Google “circle of competence” and you will get a bunch of investing-related results up top. Yet, the mental model has ubiquitous applications. We hear about it, or the absence of it, all the time. Common phrases used for being in the circle of competence are right up my alley, in my wheelhouse, cut out for this, and for being outside are fish out of water, out of my depth, outside my wheelhouse.

Our circle of competence is that area of deep expertise where we have an understanding of not just the individual components in the system but how they interact with each other. In our circle we can break things apart and put them back together without losing our way. We can explain things without jargon while also creating a new vocabulary befitting the subject being described. Our assessment of risk is accurate; our weighting of variables, precise. We’re less likely to be swayed by trends and waves. Our expertise stems from having solved difficult problems over a period of time. Having emerged from failures is a good indicator of deep knowledge, the premise being that having incurred the downside we’re more likely to know how to problem-solve. As outlined in a most memorable analogy by Farnam Street in the first part of the Great Mental Models series, if our circle of competence were a place we would be its most trusted local guide.

How do we know when we are outside our circle of competence?

Consider Twitter. All of us know it, understand how it works. And if anyone asked, we would most likely say so. Yet, only a handful of us would know about its power features that allow making lists for your interests, searching for someone’s most popular tweets, or muting words such that any mention of it or its hashtag will not appear in your notifications.

As the rudimentary Twitter example illustrates, even without deliberately over-reaching we may think knowing the surface is knowing the depth. If our bias is indeed so deep-seated, how can we alert ourselves when we have crossed the perimeter of our circle of competence? Some common signs to look out for:

Difficulty in explaining our process for arriving at a particular solution or type of solution (it depends, I go by my gut, it’s clear to me but hard to explain)

Being paralyzed by more information because we can’t separate signal from noise (we lack the necessary filtration mechanism)

Lacking a strategy outside of being opportunistic/reactive (we don’t have a plan apart from reacting to whatever’s thrown our way)

Being consistently caught by surprise (we may think we’re an expert but the world doesn’t agree, so we’re left wondering why others do not entrust us with important responsibilities.)

Experiencing a dramatic loss in intuition; this drop in the strength of our honed instincts is a sign that we are on shaky ground

Feeling the constant urge to diversify or feeling like we’re not doing enough

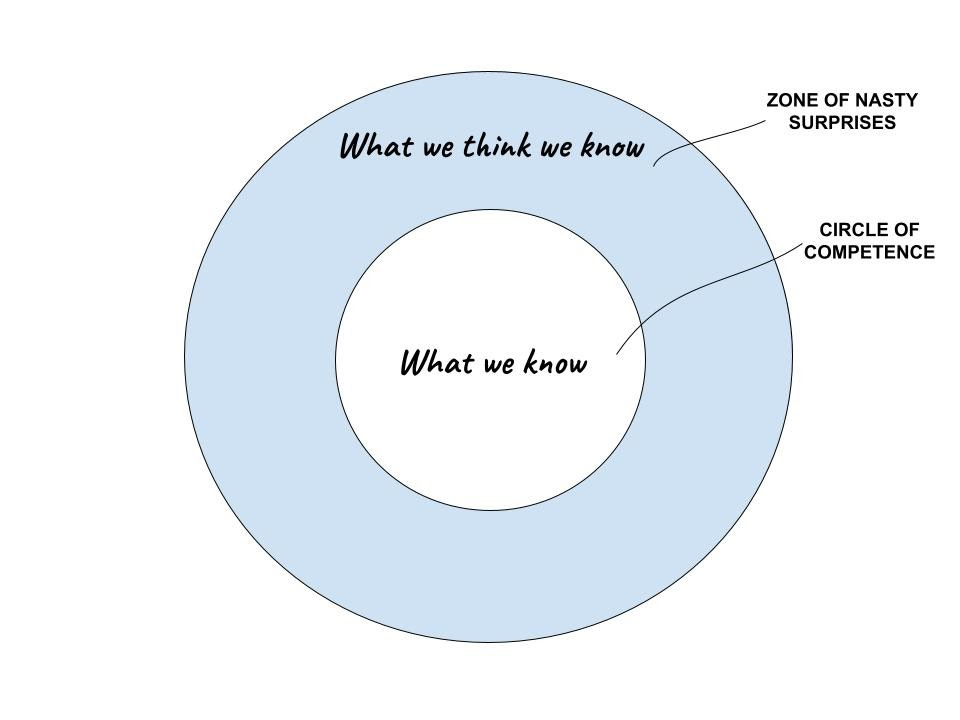

A word on being caught by surprise. In the circle-of-confidence schematic above, I’ve labeled it the zone of nasty surprises. When out of our depth in operations, our bottleneck would turn up at a place counter to expectations. In management, we would be surprised by the pulse in the team. In strategy, we would be blindsided by competition. And so on. It is the very nature of life in this zone that we’re caught off guard.

How can we build/maintain our circle of competence?

The General Mental Models Series suggests three ways to build our circle of competence.

Journaling offers a mechanism for accurate self-reporting, which protects our lessons from memory fade or self-serving bias.

Having an external feedback loop breaks any internal mirage and helps course-correct

Staying curious allows us to continuously run experiments to validate theories without letting them solidify into unchanging beliefs.

I would add three specific strategies for expanding or simply maintaining our circle.

Engaging in deliberate practice such that there’s purposeful application instead of mindless repetition (similar to what any professional athlete would do)

Going directly to the source for unfiltered information. What we see in raw data lacks any manipulation.

Forming a challenge group whose mandate it is to point out gaps in your expertise so as to help stretch your thinking.

Operating outside our circle of competence is inevitable

No matter how meticulous we are, operating outside our circle of competence is an inevitable demand of our personal and professional lives. Here the question is not of awareness but of being able to respond to situational requirements.

In my initial months helping incubate a product, I worked closely with a remote team of engineers and product people and frequently felt like I was operating outside my circle of competence. It wasn’t possible to run experiments myself or learn on my own time. I had to learn on the job--a concept knowledge workers are most familiar with.

A couple of strategies helped me stay afloat: 1) leaned on a few confidantes whom I could learn from and 2) where this wasn’t possible I went to the source for information. Talking to experts I trusted allowed me to ask foundational questions without embarrassment and helped me piece together the puzzle. I realized that going to someone closest to the problem necessitated that I learn to separate their reading of the problem from my own. This skill becomes more urgent the farther we move away from the day-to-day.

We cannot expect to start from scratch every time we venture into new territory. We can focus on building foundational strengths that travel across domains. For example, a product designer may think they need to get sharper at mocking up but what could really be holding them back is a superficial understanding of the process of problem discovery. That is the difference between designing the right things and designing things right. Knowing the latter allows the designer to switch industries. Knowing only the former pigeonholes them.

Similarly, we could look for pre-existing skills in our toolkit that are domain-independent. Any decent writer can aspire to be a good marketer by virtue of their ability to tell a story. Here’s where the model of exaptation helps us earn the functional benefits of many for the learning price of one.

Conclusion

Life outside our circle of competence levies a double tax. We pay with poor choices and we don’t realize that we may be wrong so we continue to hold ourselves at the mercy of our erroneous strategies.

“Be yourself.” Couched under these two simple words is the biggest compliment anyone could ever give us. It suggests that we possess the ability to turn our gaze inward and measure ourselves for who we truly are. Upon hearing it, it is good practice to pause and check if we know our circle of competence. As a callow twenty-two-year-old, I did not get into that business school on that occasion. I was at that point operating outside my circle of competence without knowing so. I was not ready for the compliment.