#96 - How to move from frame blindness to frame control

And avoid one of the biggest decision traps

Dear Reader,

One of life’s underrated skills is the ability to listen to well-meaning advice and pick only that which fits you. Doesn’t mean you only pick what’s agreeable or comfortable but one that is NOT out of character.

I don’t see the point in reading summaries if it stops you from understanding the crux of the topic. I don’t see the point in using ChatGPT to write if it stops you from improving your thinking about the topic. I do both—write summaries and prompt ChatGPT. But I try to be careful.

With this nudge that puts the b back in subtle, here are my takeaways for you this week. Read only these if you don’t have time. I value your attention too much to have you visit me and leave with nothing.

Takeaways:

We simplify the world in different ways, or frames. Some ways are better than others.

How we simplify the world reflects our upbringing, values, experiences. But since our experiences make up a tiny percentage of all experiences of everyone else in the world, our framing is always incomplete.

How we frame determines what remains seen and what unseen. We can only choose from what is seen.

The best decision in a losing frame is worse than an average decision in a winning frame. Work to pick winning frames.

When we frame complex problems narrowly, we’re predicting one specific out of several probabilistic outcomes. We’re betting to hit the bull’s eye. We often miss.

When no one frame captures the essence of reality, mix and match many. When you try several frames, you improve your chances of finding a solution that works across frames.

When you rush through framing, you often end up marching to solve the wrong problem. Velocity > Speed.

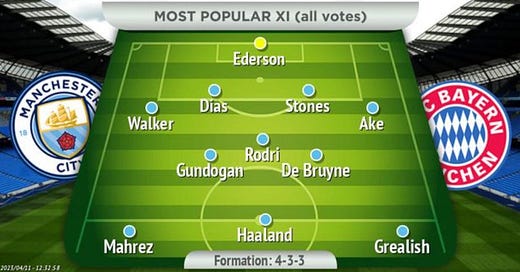

How weird it must be for Kyle Walker, England’s right back and until recently the first-choice right back for Manchester City, arguably the most successful club football team in the last decade. On Tuesday night, he found himself out of the starting XI for the Champions League quarter final against Bayern Munich.

A few days prior, over the weekend, The Guardian had reported, ‘Pep Guardiola says he has faith in Kyle Walker, despite leaving the right-back out of Manchester City’s past two Premier League matches. The England international had been a mainstay for several seasons but a change in formation and the form of others are keeping him on the bench.’

The new formation means Kyle Walker has two options. He could save his place on the team sheet by moving into defensive midfield—new territory. Or he could be on the right of a back three, instead of a back four as he is used to—also new. It’s like you spent a decade having access to a reliable budget and building performance marketing chops and now your employer has taken away all the money and wants you to kill it at growth hacking.

Not hard to see why Walker is without a place in the starting line-up.

Pic: Turns out that Walker is a fan favorite. The most popular fan XI had him in the playing XI. Unfortunately, his coach chose a different frame…

Pic: This is the actual formation that Guardiola deployed. As you can see, no place for our man Walker

Even for those who don’t understand football, the problem is clear: a change in frame. Formations in team sports are like business models in, well, business. They tell you how the team is going to play on the pitch. A change in formation is a change in frame, a change in perspective. Walker’s coach, the celebrated Pep Guardiola, has chosen to look at the task of winning football games for a profession through a new frame.

Assuming my business model analogy was calculated, why should this make you, dear knowledge worker, sit up?

Making an average choice in a winning frame beats making the best choice in a losing frame.

By now you know that Kyle Walker is the best right-back in the Manchester City squad, and among the top three in the world. Only the formation (four at the back) in which he’s the best choice for the right-back is a losing frame.

Upon being asked if Walker could fit in the new formation, Guardiola said: ‘To play inside you have to have educated movements – he doesn’t have every one of the characteristics. He has played as a full-back coming inside in the past with four at the back. He has done really well but [in] this shape of three at the back and two in the middle, he cannot do it.’

Yet, another out-of-position player in the squad, the center-back John Stones has somehow made the transition to a defensive midfielder. Is Stones the best defensive midfielder there is? Not by a long shot. I’m willing to bet Guardiola will be the first to admit Stones lacks some essential qualities in a defensive midfielder. But Stones satisfices.

Why? Because even an average choice in a winning frame beats the best choice in a losing frame. Guardiola is convinced the new frame is a winning one and his strategy is at the service of the winning frame.

A mistake we commonly make in business is that we continue with losing frames while believing that we just have to make the right choice to get the desired outcome. Well, no. It is more important to get the frame right. Here’s a blast from the past.

In 1989, Encyclopedia Britannica (EB) sold more than 100,000 copies of its ‘multivolume encyclopedia and set a sales record of $627 million.’ In five years, sales had plunged 53 percent. EB continued to cut costs and streamline operations. But they were trapped in a physical frame—they could not imagine a future where people wouldn’t read their physical books. Microsoft arrived on the scene with a new frame, a digital frame. It offered Encarta CD-ROMs almost free with its OS.

In the early 90’s the world had changed. The physical frame in which EB was an excellent brand and produced the world’s best encyclopedias was a losing one. The digital frame where knowledge was no longer the privilege of families who could afford it was a winning one. EB made good decisions albeit in a losing frame. Microsoft’s Encarta sought out EB to make a CD-ROM edition of its celebrated encyclopedia but the company rejected the offer. Microsoft subsequently slapped on Funk and Wagnalls, Collier, and New Merit Scholar encyclopedias to make Encarta. Microsoft chose a winning frame and made the most of it (even if arguably the quality of content in EB with its hundred editors and thousands of contributors was superior to that in Encarta).

Guardiola’s words may seem harsh but his thinking is consistent and he has laid it out clearly. All in 55 words. Few business leaders can do the job of articulating their frame and their expectations from their teams as clearly.

Now, admittedly, changing a frame in sports is not the same as changing one in business. Sports has the advantage of clear and near-instant feedback. Guardiola doesn’t have to wait for three months to find out if his new formation’s working. But you have to, to know if your product has found a fit in the market or if a switch to remote is working out for the org. Because feedback is slow and muddy in business, it is even more important to take the time to pick the right frame for the business problem.

If decision-making was your life, the frame you choose is your choice of a life partner. What you pick has an outsized effect on the paths that open up to you, or remain closed for ever. Given this, there are two common mistakes business leaders make when choosing a frame.

❌Spend too little time picking a frame and plunge into problem-solving

❌Exclude diverse viewpoints from the act of frame-picking

Penny wise and pound foolish

To see the snags I’m pointing to, it helps to understand the process of decision-making. Here are roughly the four stages of a decision-making process that we, consciously or not, go through in arriving at a decision. To give it some depth, imagine you’re the CEO of a company and you’re facing a situation of declining sales for your flagship product.

Defining the problem (or framing): The first stage involves identifying the problem or opportunity that needs to be addressed. For example, you might attribute declining sales to the problem that your product is priced out for customers.

Gathering information: After defining the problem, you set out to gather information that’ll help you evaluate your options. This might involve collecting data, conducting market research, or consulting with pricing experts on how to be more price-competitive.

Coming to a decision (after evaluating options): With the necessary information in hand, you can then evaluate alternative courses of action. This might involve thinking about where to cut costs and looking at the trade-offs. Finally, you wrap it up by coming to a decision.

Learning from the decision: This step doesn’t always pan out because humans are lazy and goal-oriented but assuming it does happen, what do you do here? You execute the pricing change and you track results. Have your sales stabilized? Have you regained market share? You try and learn from the experience so as to be wiser, smarter for the next time round.

Now imagine if you had originally defined the problem not in a pricing frame but in a value frame. Imagine saying, ‘Let’s cut costs without cutting down on quality so that customers don’t feel they aren’t getting bang for their buck.’

Or perhaps you wondered, ‘Where can we cut costs and put a portion of that savings into improving quality such that customers are delighted? And let’s charge a premium for that.’

But none of them came up for consideration because you didn’t set aside time to frame the problem right. You plunged or had your team plunge into problem-solving when a separation of the act of problem definition from that of problem solving would have served you better. Why does this separation matter?

For each of these frames, you’re likely to look for different sets of information and see different options emerge. The frame decides what part of the problem landscape comes into view and what remains hidden from you. You cannot fix what you cannot see.

As if the fact that you can only pick a frame that is at best a narrow reduction of reality wasn’t a problem enough, your position in the pecking order can make it worse.

Your team may dutifully, or grudgingly, accept the frame and proceed to gather information necessary for a resolution within that frame. Very quickly they may run into rough weather.

As the directive cascades down the ranks, the team doesn’t know what exactly to look for or how to find it. They pull in the bosses within reach. At this point, one of two things may happen. Strapped for time, you let the team proceed with their grasp of the problem frame and go on to collect information and produce the best possible options. Or you try and fix any misdirection before the project’s too far along. When you do this, it’s likely that you’ll end up spending a frustrating amount of time gathering information yourself. This has a big opportunity cost because it comes at the expense of something else you cannot delegate. At this point, you may be tempted to call up your fellow executive friends to gripe to them over dinner, not realizing that a contributor to your helplessness is your problem framing and failure to communicate.

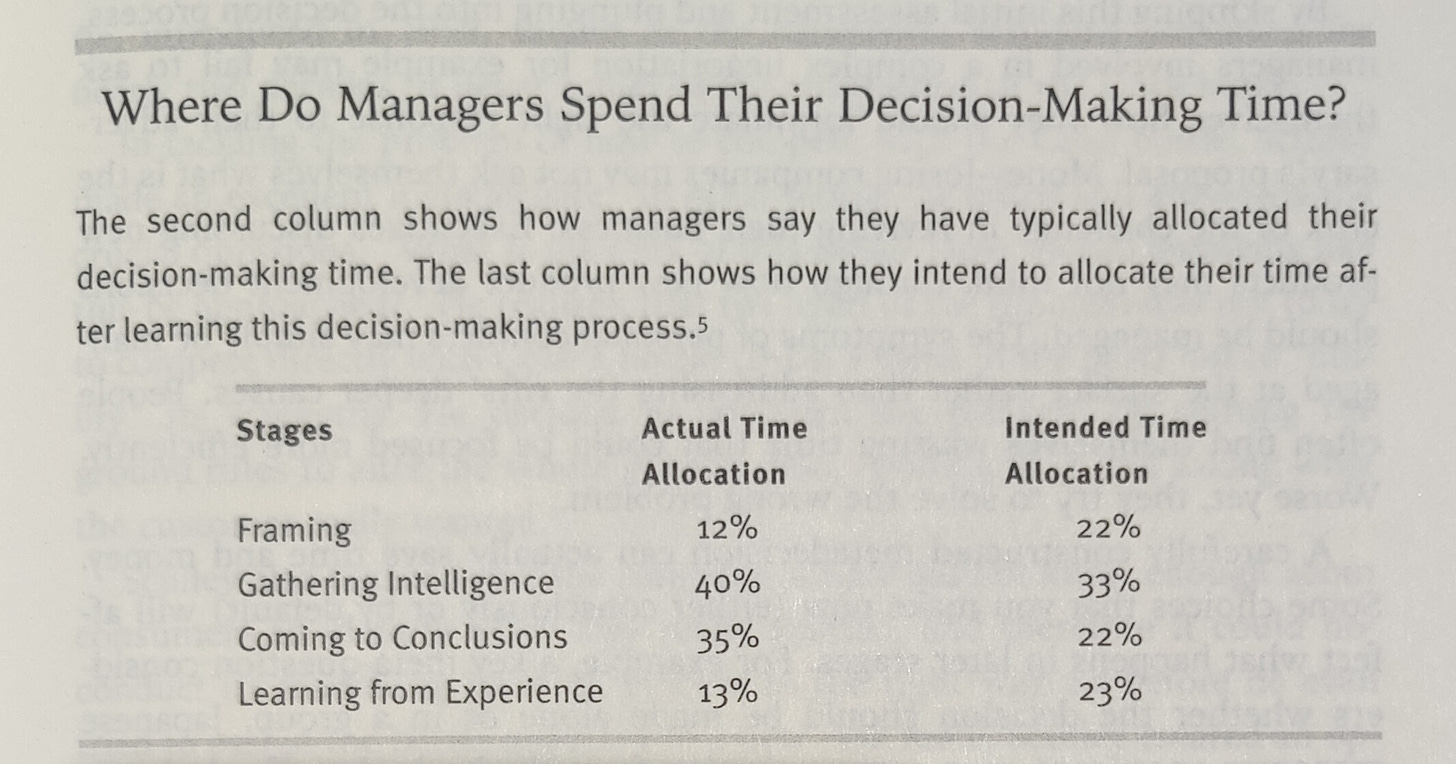

Unfortunately, this kind of skimping on decision-framing is common. When the authors of the book Winning Decisions asked ‘participants in our executive education seminars how they allocated their decision-making time,’ the executives reported the table below.

With some things in life, messing up at the start is not the worst thing to do because there’s a second chance coming your way later on. Not quite with mis-framing. It throws a double whammy at you. It doesn’t matter how much time you spend on framing if you spend all that time on it alone.

When invisible becomes transparent

When you consider a situation, a question, a problem, your system of beliefs and experiences reflexively puts boundaries on it. That’s your default setting. Your default setting is probably obvious to those around you, but not to you.

In a 2017 blog post, coder John Salvatier, reflecting on his staircase-building teenage years, suggests what may happen when our frames are invisible to us.

Frames are made out of the details that seem important to you. The important details you haven’t noticed are invisible to you, and the details you have noticed seem completely obvious and you see right through them. This all makes it difficult to imagine how you could be missing something important.

What Salvatier seems to be saying is what Danny Kahneman has captured succinctly: You’re blind to your blindness.

Unless you invite others to take a look, you will continue to remain blind to what you don’t see, no matter how eclectic your experiences, or how multidisciplinary your thinking. There’s simply no substitute to more eyes when it comes to picking a decision frame.

That brings us to the second of two errors you may make as a business leader while choosing decision frames: you don’t generate enough alternative frames to pick from.

Your best chance of finding a frame that best captures the essence of a problem is to share it with others who can then inspect it from their unique vantage points. All at once, you’ve a botanist, a forest ranger, and an environmentalist looking at a national park.

Sounds simple but here’s the rub. It’s not much use if you get this crack team to chime in after the problem has been defined. You need them to work with you before you’ve solved the problem.

This, again, is common in large organizations. You may hire folks of pedigree but bring them to the table too late in the day. They can only deliver within the confines of the frame you’ve set for them, not find you the most appropriate frame for the situation. They cannot unlock you from your own narrow frame.

The art and science of reframing

Say you’ve built this habit around framing. You’ve set aside time to pick a frame in your decision-making process, you’ve brought in others to challenge your frame and generate alternative frames, and you’re geared up to work with your team to pick a winning frame. How do you do that?

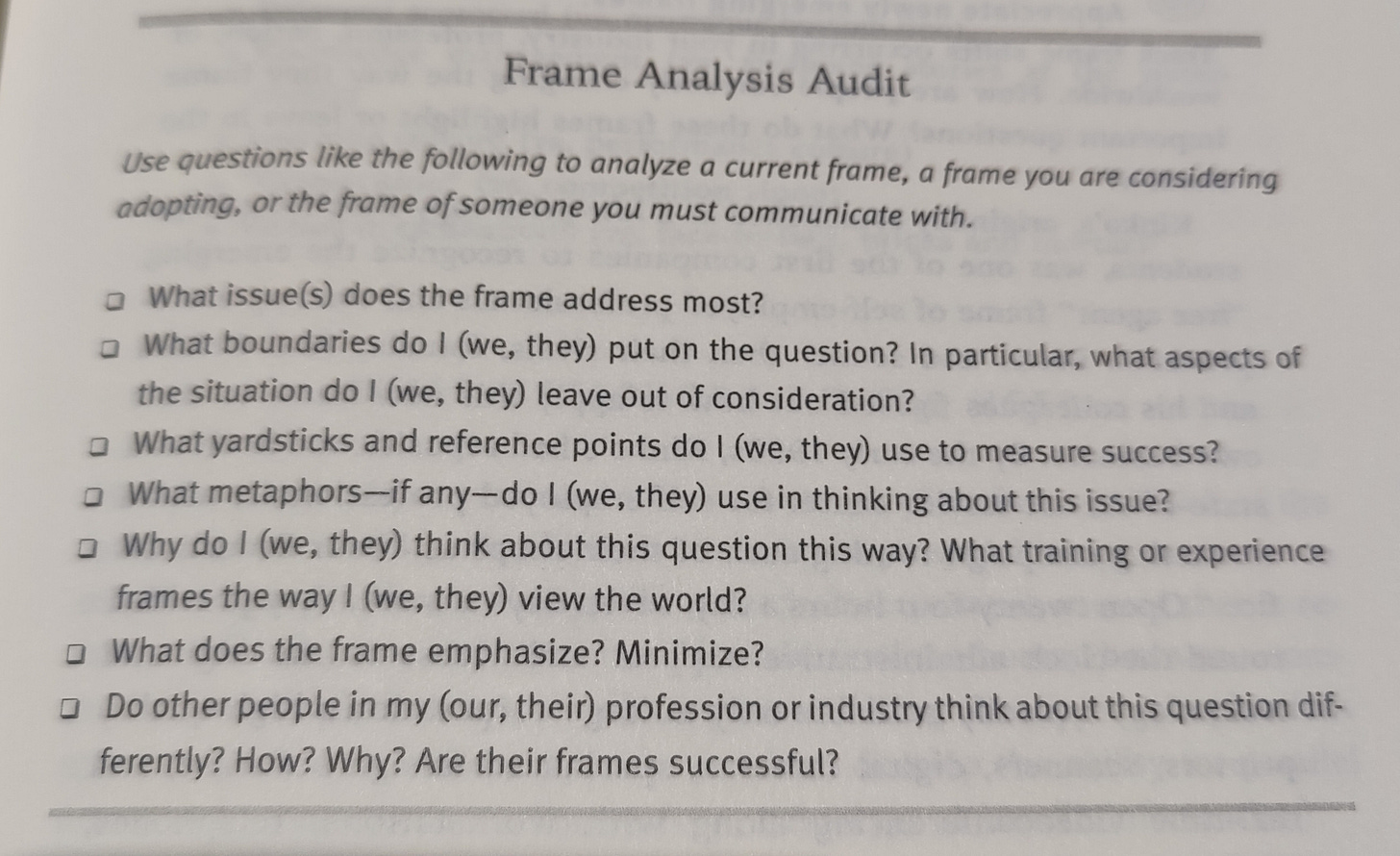

Consider this non-exclusive list of behaviors and actions, lumped under frame awareness and subsequent evaluation:

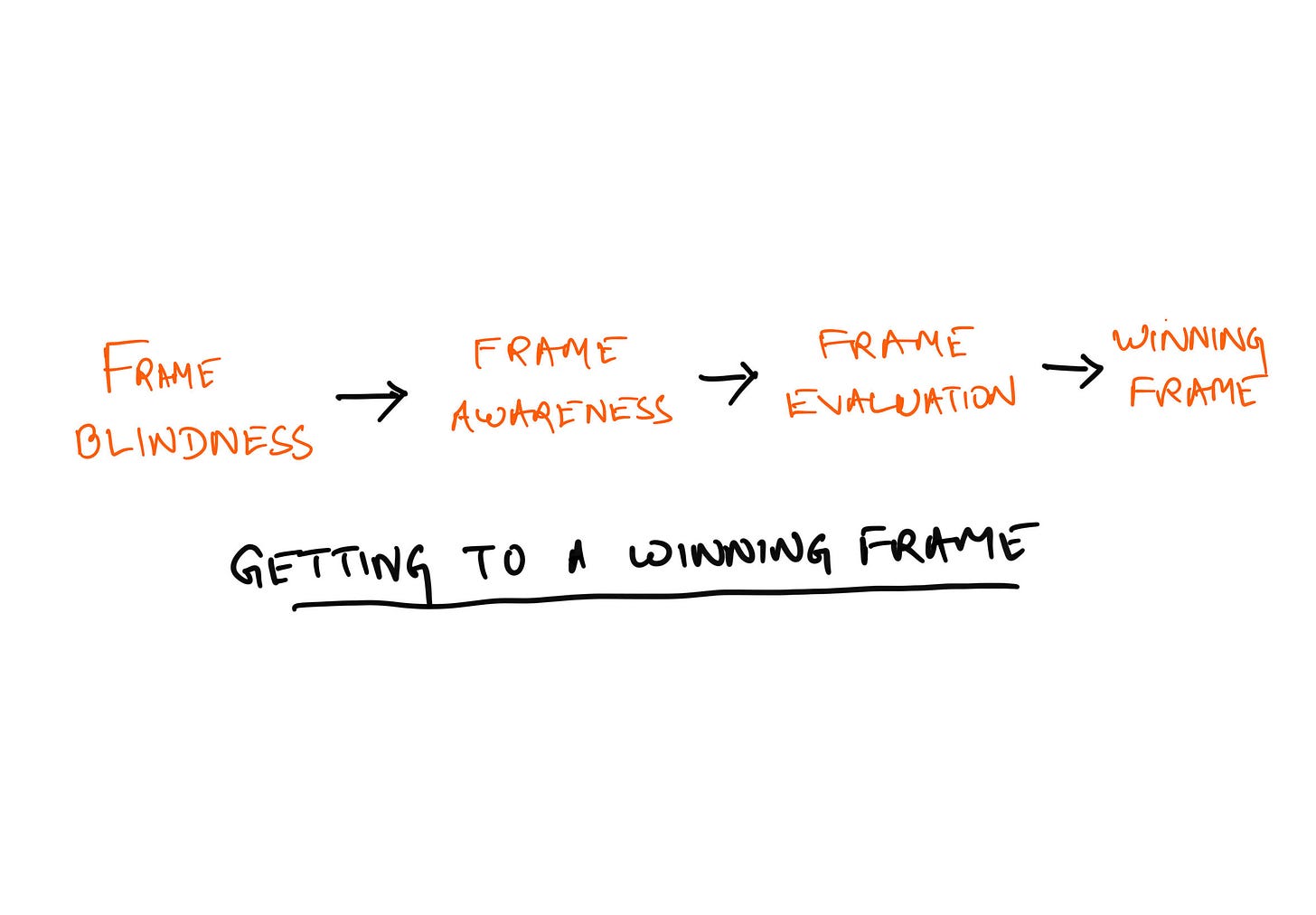

Frame awareness

Hire heterogenous people (heterodoxy is a better eraser of blind spots)

Ask your team to name your top 1-2 frames (gives them permission to break rank and make you aware of your default setting)

Uncover your default frame by using a checklist (here’s one)

You’ve now moved on from a state of frame blindness, which most are stuck in, to a state of frame awareness. Recognizing the bounded-ness in your thinking most likely will leave you with an urgent itch that you will want to scratch right away. And that’s a good thing.

Frame evaluation

Challenge your frame (try to falsify your assumptions)

Use different metaphors (military or sports metaphors see problems as zero-sum; art sees creation as positive sum; and so on)

Mock existing yardsticks and reference points (here are some extreme prompts for brainstorming)

Find someone who’s solved your problem and learn from them (get inspired by laddering up beyond your immediate company)

Turn logic on its head (some old buildings don’t lack an elevator; they offer free cardio by way of a staircase)

You’ve done the hard yards. You’ve challenged your default frame with the intent to loosen its grip on your thinking. You’ve generated multiple frames with the intent of picking the best one. This is where I’ve good news and bad news for you.

The bad news is that not always can you find that one winning frame that fits the scope of your problem in all conditions. Real world is complex. There are many ways to look at it. Think of the many product prioritization frameworks or the different valuation approaches. Real world also allows combinations if you’re willing to do the combining. If no one frame is complete, the least incomplete frame is a blend of multiple frames.

The good news is that by putting yourself and your team through the rigor of frame selection, you’re likely at least to end up with an acceptable option that works in multiple scenarios. That is the best under the circumstances.

Decision coach and writer Shane Parrish often talks about this as positioning. Positioning is nothing but picking a frame that works in multiple versions of the future. It doesn’t depend on the future turning exactly as you’ve predicted. Instead of being absolutely free in only one version of the future, you’re reasonably free in any of several futures that await you.

A well-chosen frame preserves optionality. It doesn’t guarantee success but it reins in the chances of failure.

***

Thank you for your attention. I hope this was useful for you. Drop a comment to let me know. Or share your experience of managing teams. I would love to hear from you.

Remember to read what you write aloud. See you soon!

I have been going wide and then deep in most of my problem solving discussions.

Wide phase is the one for exploration, mapping all possibilities not just from this context but from others and identifying possible anchors that can be picked up.

Deep phase is to pick one of those anchor and then go deep to find the solution. If we get stuck and don't find sufficient water, we get back to exploration output & pick a new anchor.

'Framing' feels like a good way to imagine this approach. Thanks for the clear articulation and the example to make this one more memorable.

Love this one! Raise the floor & think in expected value with your decisions.