#92 - How did Iceland get its teenagers to voluntarily stop chasing the high of drugs and alcohol?

And what can organizations learn from Iceland's story?

‘In 1997, a photograph was taken in downtown Reykjavik, Iceland, that would later become emblematic of a major national problem. It shows a city block jammed thick with people—the heads are mostly blond, with a few brunettes sprinkled in. It’s summertime in Iceland, when the sun doesn’t really set so much as take a breather for a few hours. So even though the photo was shot at 3:00 a.m., all those faces are pretty easy to see, and almost every last person in the picture is a drunk teenager.

The teens have taken over the city.’

This is the opening of a 2020 piece by author Dan Heath titled To Solve Problems Before They Happen, You Need to Unite the Right People, published in Behavioral Scientist. His book Upstream, published earlier that year, has a full chapter dedicated to how corralling the right people is a must for business leaders looking to stop problems before they happen.

Hello and welcome to issue #92 of Curiosity > Certainty 👋 This week we’re throwing light on the largely neglected path of problem prevention. But before we do so, if you’re still wondering about the 3am habits of Icelandic teenagers, this is the picture the article (and the book) references.

Source: Inga Dóra Sigfúsdóttir, Planet Youth

Iceland’s earlier efforts at curbing the problems of teenage drinking and substance abuse as they crept up through the 1990s involved, among other things, mandating the hours when kids could be outside. How did that turn out? ‘All those kids jamming the streets of Reykjavik in that memorable photograph, for instance—they were all breaking the rules,’ writes Heath.

Why am I telling you this?

This mirrors what happens at organizations that you and I are a part of. Maybe at different scales but the pattern is unmistakable.

Here are some things you may recognize:

Many business functions bear the consequences of one or more recurring problems, yet it is no one person or unit’s job to fix them for good.

There have been past attempts at correction, the increased policing Icelandic equivalent, but they have failed.

Every day/week, a portion of your time goes into firefighting. These are barn-burning emergencies that you did not plan for at the start of the day/week.

Everyone sees the problem and discusses it but they don’t see their role in propagating the problem.

Decisions taken in a certain context are replicated in another and much to everyone’s surprise result in suboptimal outcomes without acknowledgement of the change in circumstances.

I could go on, but you get my drift.

Why does a culture of problem-solving drown out problem prevention so often?

In a 2002 paper, three researchers from Harvard Business School spent 197 hours across 8 different hospitals observing nurses. Nurses were chosen because obstacles are dime a dozen in their line of work: missing tags on newborns, broken equipment, missing prior reports, waiting for a limited resource, incorrect medication, and so on.

The study found that the nurses did what it took to continue taking care of the patient. They tended to not disrupt their routine to raise red flags or to investigate or even to report to someone better placed to fix the problem. Their behavior exhibited what the paper calls ‘first-order problem solving’---solving a problem or curbing its effects as they occur. The nurses did not pause to fix the underlying causes to prevent recurrence (second-order solution).

Those were nurses; maybe that comes with the territory, you say. Well, here are some signs that first-order solutions are being employed at your workplace:

Work doesn’t stop - Front-line workers (those in execution) have customer deadlines. In Customer Service, it means continuing with customer calls; in Operations, carrying on an assignment for delivery later in the day. This leads to propagation of problem-solving behavior. This is not a bug; this is a feature.

(There’s another barrier to finding the root cause of the problem: not knowing whom to approach for help. This can cause frustration and paralysis, so sharing tends to take the form of venting and is limited to immediate peers.)

Processes don’t change - Because of #1, information about snags in the process is lost. The spill is cleaned up, the floor is mopped, details are forgotten.

New members in the system find the way things are done unusual - They may or may not voice it. Before long, they are a part of the way things are done.

The same cycle repeats itself.

And because of the everywhereness of this behavior in organizations, it is more common to:

👉Hire more call center representatives to manage bigger call loads

THAN ensure customers are getting what they want and don’t have to call at all

👉Drop the price if sales are lukewarm

THAN have customer conversations before designing your product

👉Add more fire trucks to your station

THAN look at what’s causing all these fires in your precinct year on year

Where to start?

Here’s a screening question I’ve come up with that you could ask yourself first to get clarity:

‘Am I making an early-warning system so that the problem doesn’t occur OR am I making a rapid-response team to solve the problem quickest when it occurs?’

👉When trying to prevent a problem, a whole cross-section of people have to chip in to make sure it stays that way. There’s a shared goal: prevention.

When designing a system to prevent problems, the consequences are far more complex and multi-dimensional than any one person or team can anticipate. You need many and unalike hands on deck.

If you want to wipe out domestic abuse, cops have to do drive-bys, social workers have to do check-ins, medical workers have to report incidents. Being proactive means everybody has to chip in.

👉When trying to solve a problem, involving too many people means they’ll look to deflect blame off themselves first. There’s no shared goal. There’s only an individual goal for each: preservation.

As a fan of the police procedural format, I know that detectives get the most out of a crime scene. If you round up the lieutenant, the chief of police, all the way up to the Mayor to solve a homicide, be prepared for finger-pointing.

Being reactive means only the specific group should be called for. The rest should continue on. Because reacting is disruptive.

✔Surround the problem with the right cross-functional group if you wish to stop it from happening.

❌Don’t deputize a big group if you’re only addressing a symptom of the problem.

Sounds easy but is not. I’ve worked cross-functionally all my career and I continue to learn one simple lesson the hard way: Very few teams (only the best) pause and spend time on identifying and aligning on the root problem.

Whom to rope in, when to rope in

If you’ve decided to uproot and not trim, remember that you have a goal that has to be shared by many. Upstream action is multidimensional, broad. To stop a pimple, you need to eat healthy, sleep on time, weed out stress and still keep your fingers crossed. Who influences kids? Well, everyone from parents to teachers to coaches to friends. Once you have your many hands, you need to have them joined. So: get all major influences in the room early on. Get them to own the problem. Give them each a role.

If you’ve decided to trim and not uproot, know that too many cooks only end up pointing fingers at each other. If you’re not solving a problem upstream, don’t bring everyone to the table. There won’t be enough meaningful work to assign to people. They’ll own the problem less. This is what can happen in organizations that allocate cross-functional teams to address issues downstream.

A common example for this is review meetings for a product or a campaign. For years, my crippling fear has been review meetings that drown in detail but don’t deliver breakthroughs. Why so, you may wonder?

Data is not supposed to be useful for leadership, so that they can diagnose problems with a click. Data should service those on the front line, so that they can make the necessary corrections in time.

Leadership doesn’t need data to learn. By virtue of their position and priorities, they’ll use data to inspect. Why are our Google CPC numbers up? Why is our NPS score down? Who’s in charge of this?

Once this happens, people start protecting their turf. They point at the budget, an absent team member, too many things on their plate.

A common by-product of a culture of data for inspection is super-defined roles. Because if people are going to be scrutinized, the first thing that makes sense to do is draw boundaries. Few are keen to own the problem.

The more roles you create, the more cracks you create between those roles. If you don’t pay attention, ownership slips through those cracks.

How do you ensure ownership?

Know-why and know-how: my personal experience

I’ve always believed know-why should be included in briefs to front-line workers (‘We’re doing this because… and not because…’). When I was in the weeds, I often found myself hamstrung with just know-how because it didn’t allow me to fix problems for good. I would always have to take it to someone more experienced and/or with authority.

The common argument against sharing know-why is that it can overwhelm workers. I tend to go against this notion. People are smart; information framed well answers most questions and prepares them to face contingencies.

When I started leading teams, I took to explaining the why to my team. Doing so took time initially and sometimes I couldn’t be sure right away if sharing the why helped. But over time it would be as clear as day.

When I was away from work, I would see most clearly the impact of sharing the know-why. The team would know when and what to fix (or not) if they knew why the processes and systems were set up the way they were.

This is just one strategy I tried. Research offers several more to founders, leaders, and managers who want to see ownership and problem prevention in their teams:

Create slack in schedule.

Lower barrier to flag-raising.

Show that you take complaints seriously.

Offer easy access to appointed system thinkers.

Reward a captain’s mindset much like you reward a firefighter mindset.

Ensure employees don’t mix resourcefulness for being left to their devices to fix problems.

How did Iceland save its teenagers?

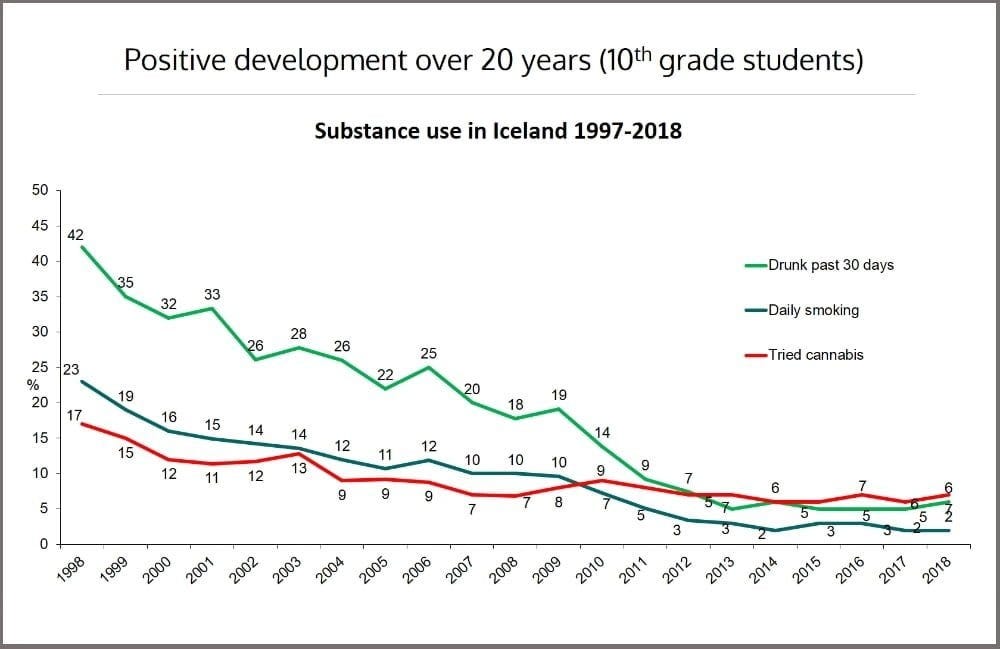

Some facts, as of 2016, from the same Dan Heath piece: ‘Today, Iceland tops the European table for the cleanest-living teens. The percentage of 15- and 16-year-olds who had been drunk in the previous month plummeted from 42 percent in 1998 to 5 percent in 2016. The percentage who have ever used cannabis is down from 17 percent to 7 percent. Those smoking cigarettes every day fell from 23 percent to just 3 percent.’

Source: Upstream by Dan Heath

To nip the Icelandic crisis in the bud, parents kept street vigil to dissuade teens out during late hours (instead of cops making arrests), coaches formed sports leagues to make recreation purposeful for kids (so that kids chased the natural high of sports, not the artificial high of drugs), and the Reykjavik city government offered ‘gift cards worth hundreds of dollars, to spend on membership fees or lessons.’

It helped that Iceland is a tiny nation, with the vast majority of its population living in or around Reykjavik. But the Icelandic template offered enough evidence for it to be copied by Spain, Chile, and Romania. Who would’ve thought teenagers the world over were a problem!

What if you find yourself leading a team in an organization that wants to learn and change for the better?

Problem prevention is often seen as extra work. It tends to be voluntary for that reason. But voluntary doesn’t mean left to chance. The mistake organizations make in an attempt to seize control of their change story is that they mandate top-down change.

An HBR article by a group of organizational behavior academics states that top-down corporate change programs typically do not translate into lasting change. Companies that have lasting positive change to show didn’t ‘employ massive training programs or rely on speeches and mission statements.’

Instead, they create a climate for change, then share the lessons of both successes and failures. A firm open to change and hence to learning needs managerial emphasis on ‘task alignment’—a situation where employees’ roles and responsibilities are in line with a shared organizational goal. Such alignment usually happens on the fringes and gradually moves toward the company core.

So, go ahead and create a climate for change. The odds are on your side.

***

Adios for this week, friends. My highlight for this week has been throwing a bunch of fun prompts at ChatGPT4 and getting it to decode published papers on organizational behavior, decision-making, and change management. As a non-academic if one of your barriers to understanding primary research has been the dense formal style in which science is reported, fear no more! You’ve help now. Until next week…