Dear Reader,

I have been on holiday here in Australia, first Sydney and now in Melbourne, for a week and the first arresting moment arrived on the first afternoon when I went out to Coles (a supermarket chain) to grab a few things.

As I used the self-service checkout, it became clear that I could get away with more of certain categories of items than I was willing to pay for. If I scanned a peach, for example, the system asked me to enter the number of peaches I was buying. I could enter a number of my choice. There was no one to check.

And then I started noticing the same trust elsewhere. There was no checking of bags as one entered or exited supermarkets or liquor stores in malls. No one asked you to deposit your bag at entry and collect it back at exit so as to stop you from putting things in your bags.

My wife and I used trams, buses, and ferries to move around with our toddler. My daughter is pushing three. Her rides were free. Still no one asked us for age proof for her.

These experiences have left me wondering: what is the price we pay for mistrust?

In India the cost of mistrust is the salaries of bag checkers, watchmen, and other minders at various public and private places. It is hard for me to imagine similar experiences in India, as I have described, without the presence of some sort of a checker. Labor is cheap in India. Mistrust is affordable.

Is it?

The price we pay for mistrust is that we turn social exchanges into economic ones. There's a protocol to be followed that takes who you are out of the equation. There's no implicit expectation of you as a responsible member of society—or rather, there is. But that is not all. There's some watchdogging to make sure the protocol's followed.

It is energizing to live in a world without having to pay a mistrust tax. Not that the tax is too high materially (in India it isn't), but the tax system reduces the experience.

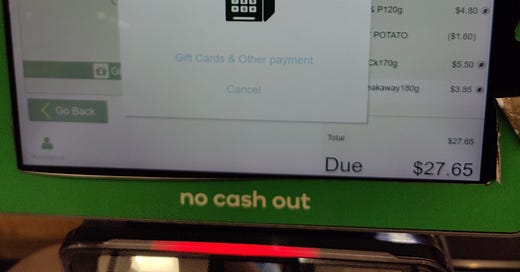

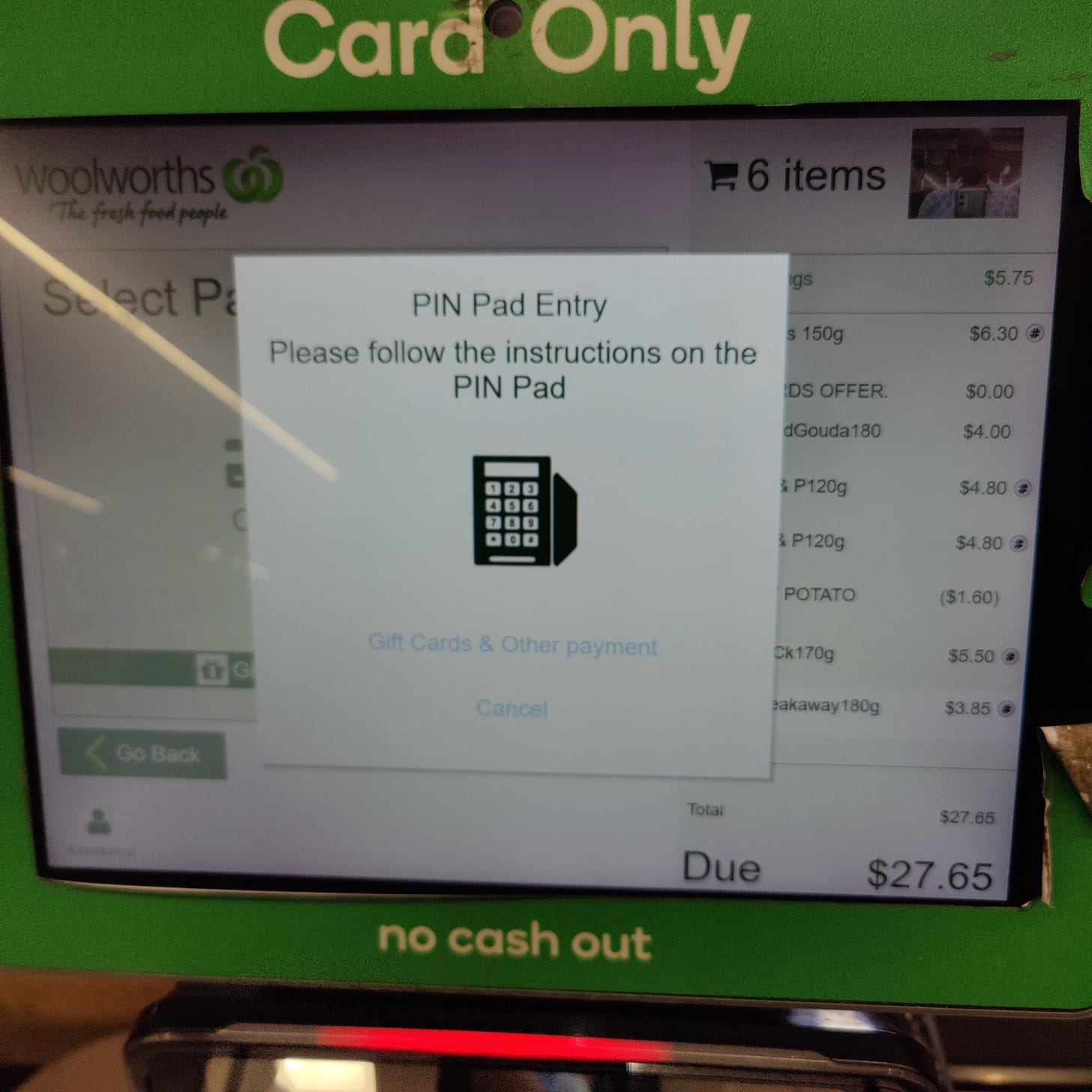

It didn't occur to me to take a snap as I was scanning the items. But this one above should give you an idea. My six items could have been four or two. No one was there to check.

The magic of paying attention

I have been impressed by the Australian sense of design. Not a specific style or school per se—I wonder if there's one such monolithic idea—but the attention people here pay to how things appear. And by extension how they make you feel.

Wherever I have looked I have seen beautiful design. Shop signage, logos on buses and trams, labels on locally brewed beer.

Busways, New South Wales logo

New South Wales public transport logo

Attention to the little things elevates the experience not just for the receiver but also for the giver. Seeing such well-crafted designs made me want to believe that the people responsible for them wanted to build something to last.

How would you build something if you wanted it to outlive you?

The planning fallacy…

Public projects, more than anything, are known to bloat and exceed originally drawn budgets and timelines. If you've ever managed a project at work or home, one involving others, you would know the feeling of losing control as the deadline approached. We display infallible optimism when it comes to projects we undertake on our accounts. This is the planning fallacy.

I'm going to track the completion of Sydney Gateway.

******

That’s it for this week, dear friends. I'll have something to say next week, holiday schedule permitting. Until then, stay good.

This touched me. I have been questing how one should live their life in India, I live by default trust which has led to betrayal be it a fraud or a shopkeeper charging extra. I feel irritated, anxious with this, and every time this happens I lose hope.

Your view just took me back to my trip to Dubai last week, there is no one to check in bus if you have paid since there is a card system, and so in the whole city.

And I would love to explore what does this mistrust cost to individual? Make them sinical?

Any thoughts?

I would rather live by trusting then by mistrust filled inside me. And the cost we pay is high, social experience to economic!