#83 - Decision-making for a high-school chemistry teacher, a cancer patient, a drug lord

Part 2 of essay on stepping forward to life's deepest questions

Hello, friends! Welcome to issue #83 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏 I’m Satyajit and I love writing about all things decision-making.

This week’s issue continues the exploration of a class of decision-making challenges called wild problems. You can catch the first part here, if you haven’t already.

In response to the first part of the essay, a reader drew parallels between wild and wicked problems. He mentioned that ‘Various fields have discussed these kinds of problems and understood that they can’t be solved using normal methods.’

By normal, he meant rational. My understanding at this point is that the most telling distinction is that wild problems are of a personal and transformative nature while wicked problems are of a social and irreducible nature.

And the most telling parallel to me is that solutions to either kind of problem are not true/false but good/bad. Perhaps it is this aspect that I find most fascinating about this class of decision-making challenges which are at the heart of life’s biggest questions.

Let’s go!

The inner and outer lives of marriage–A case of the vampire problem

Why is the inner life inaccessible?

For choices involving radically new experiences, we are confronted by the bare fact that we can know very little about our subjective futures. We may form a better idea of the objective aspects (outer life) by talking to people who’ve been where we want to go. This bridges the objective gap between our lived and unlived experiences. But it still reveals nothing about the subjective aspect (inner life) of who we’ll become when immersed in that yet-to-be-lived experience.

Philosopher L.A. Paul says in her book Transformative Experience, ‘Many of [life’s] big decisions involve choices to have experiences that teach us things we cannot know about from any other source but the experience itself.’

We all yo-yo while making decisions about the biggest unknowns in life. Formal decision-making analysis works only so much there. There’s a big assumption in our rational attempts to narrow down choices that we gloss over. That assumption revolves around what is called the vampire problem.

Paul devises a clever thought experiment to describe the vampire problem: You are offered a chance to permanently turn into a vampire without pain, for you or for others. You will gain incredible vampire superpowers in exchange for giving up your human existence. All your friends have made the switch and are loving it. Would you take the offer?

The vampire problem illuminates another item on the calling card of wild problems: they are hard to reverse, if not irreversible.

You can’t simply undo it once you’ve done it. Shown a two-way door, we would have not agonized nearly as much over the decision. But once we know that the door will close behind us once we pass through it, we break into a cold sweat.

Paul writes, ‘You cannot make an informed choice when presented with the opportunity to painlessly turn into a vampire with your friends and loved ones already having made the transformation. Because you don’t and can’t know what it is like to be a vampire until you become one.’

We can tag along with other couples or listen to the testimonies of that aunt and uncle who recently celebrated their golden jubilee, but we cannot imagine the spouse or partner we will be in the same situation. We cannot get a taste of life inside when we’re outside.

We can only know what it is like to be a vampire by becoming one.

Walt White didn’t end up a vampire, but he chose a monster

A 50-year-old high-school chemistry teacher finds he’s dying of cancer. That medical verdict sets off a process of two transformations. One quick, the other slow.

Before we dive in, a word about classically rational decision-making. Such a process is straightforward, if not simple: you take an option, you map out all reasonably possible outcomes emerging from it, you order them as per your preferences, you tag a probability to each outcome, you get the expected value or payoff for each outcome by multiplying the outcome with the likelihood of occurrence, and you add all the expected payoffs. Finally, you do this for all other options and you pick one with the highest expected payoff.

You’ll hear this model by different names: as the ‘normative rational decision-making model’ by L. A. Paul or as ‘the 3P’s model’ (preferences, probabilities, payoffs) by decision strategist Annie Duke.

Let’s use this model to dig into the transformative story of Walt White, our high-school chemistry teacher.

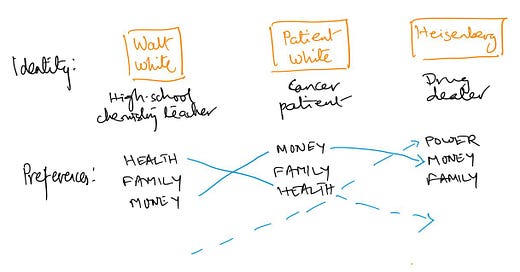

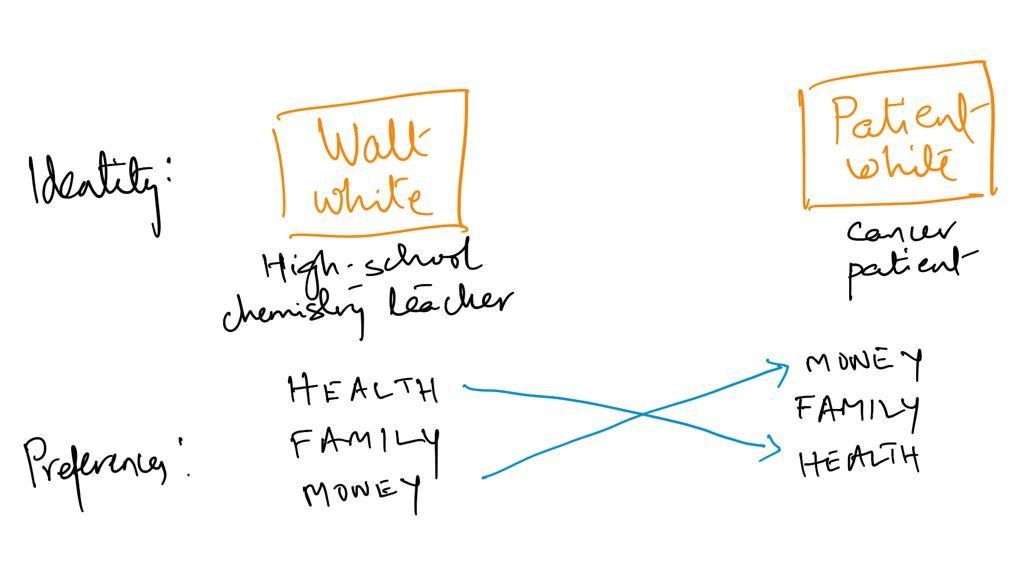

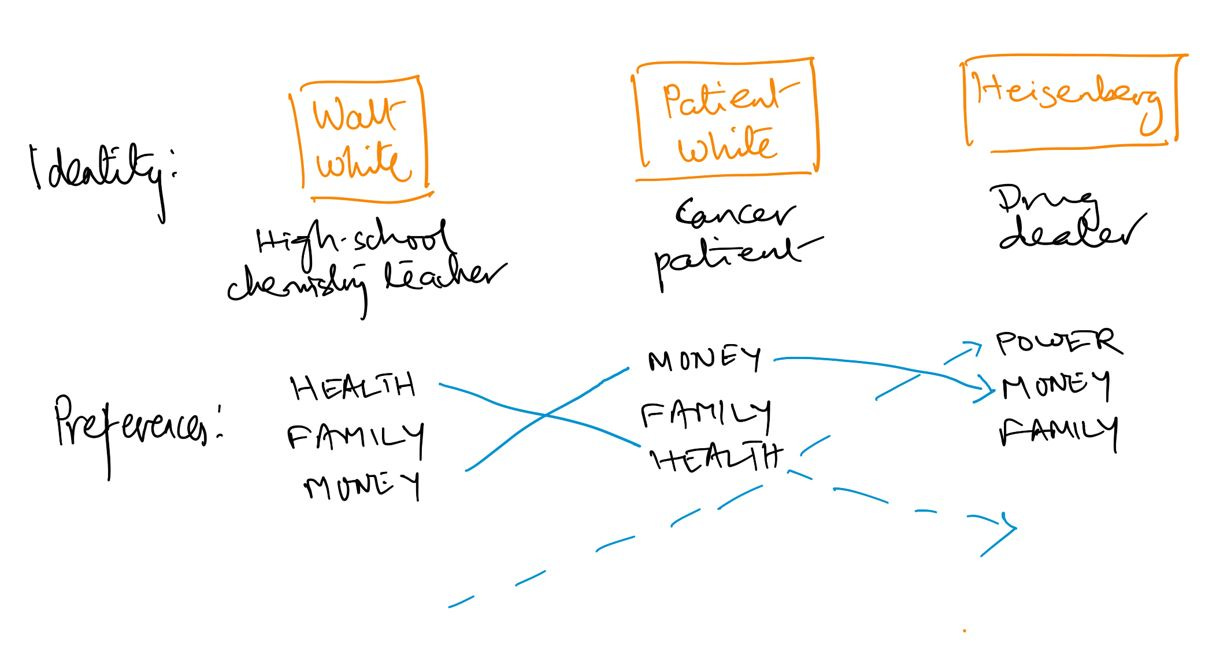

First, Walt White, the anti-hero of the show Breaking Bad, becomes a cancer patient. He is at once living with a new medical truth that changes what is important to him. Providing for his family after he’s gone becomes most important to him.

Side Note: Around the time he’s diagnosed with inoperable cancer, Walt White also finds out that he’s going to become a father for the second time. As transformative as the experience of fatherhood would’ve been by itself, combined with cancer and the prospect of providing for his disabled teenage son, it rattles his core.

The subjective value of his life-changing experience as a cancer patient has two parts to it: the experience of what it is like to be a cancer patient AND the experience of what being a cancer patient is like for him.

The first part is what makes his experience ‘epistemically transformative,’ to borrow a phrase from L. A. Paul. He could have listened to a thousand accounts of other cancer patients, he could’ve cared for a family member afflicted with cancer, yet none of that would have been adequate or accurate enough to reveal to him what it is like to live with cancer. The experience of having cancer brings him information he could not have got any other way.

As irreducible an epistemic (or knowledge) transformation is, it can happen to us outside the dire circumstances of cancer. Travelers make knowledge leaps in a new country, scientists do so while making breakthrough discoveries, and lovers pull them off when trying a new position. And babies, with their bare cupboard of experiences, have it all the time–first time tasting ice-cream, first time by the beach, or first time watching a butterfly.

Seen through just the knowledge lens, the new and rich information about the world of cancer doesn’t change the preferences of Walt White.

It is the second part of Walt White’s cancer experience that is, to quote Paul again, ‘personally transformative.’ The core values of the cancer patient are totally different from those of the high-school teacher. This heavy edit of his preferences edits the experience of being Walt White.

And it is this final, slow, value transformation that drives the narrative arc for Breaking Bad. The once-transformed Walt White transforms again. He breaks bad, making a series of choices that prove life-changing. The best choice, with the highest payoff, for the crystal-meth-making Heisenberg is radically different from the values of the cancer-patient White, much to the shock of his family.

Walt White and Heisenberg want different things from life. They want different lives.

Walt White’s decision to break bad does not fit the rational model. His law-abiding healthy self could not have made the choice to turn into the dreaded Heisenberg after a process of careful calculation. That’s what makes his problem a wild one.

Advice for a younger self falls on deaf ears

Here’s what we’ve learned about transformative change.

It is not just that the experiences of others are unknown to us. It is that even what we know about ourselves at one point in time may remain unknown to us at another.

When those in their 30s write about ‘Things I wish I knew in my 20s’ they wash over this fundamental truth about transformative change.

Even if you had access to the advice in your 20s, you would not see it as someone with the life experiences of a 30-something. A full appreciation of middle-aged wisdom can only come with middle age.

As a 30-something you may look back at your decade-younger self and wonder ‘What was I thinking?’ just as, as a 20-something you may look at those in middle age and caution yourself, ‘That’ll never be me!’

A key aspect of the difference between your 20- and 30-something versions is the knowledge gap between them. It is impossible for the graduating you to project forward and imagine what it is like to have a job, a house, a partner, kids.

This is where being objective brings only an illusion of knowledge. No matter how clearly you think, you cannot appreciate what it would feel like to spend a Saturday afternoon watching your kid’s soccer game or sleep in early on the weekend to get a jump on Monday morning.

In the movie Sound of Metal, Riz Ahmed plays a drummer who has lost most of his hearing. He admits himself to a community for the deaf. The community follows the Deaf (with a capital D) culture. The members don’t believe deafness is a disability that needs to be cured; rather it is an experience worth having, celebrating even.

Riz, holding on to the dreams and beliefs of his hearing-abled self, imagines himself better off living in an RV and touring the country. He undertakes a series of steps to get cochlear implants, which he believes will lead him back into this earlier life. Only the experience of being restored to a person of hearing with the implants is nothing like what he had projected forward in his head. In fact, he wonders if there has been a restoration at all. He has lost his identity as an accepted member of the Deaf community and he no longer can grasp what it means to be anything else.

Riz made a bad bet about his own life preferences. He thought he wanted something. Turned out not. Such a distinction between the expected and actual is at the heart of all wild problems.

***

Thank you for reading! I would love to know what you make of this long-form piece and how I could make this newsletter more useful for you. Drop a comment. Write to me at satyajit.07@gmail.com.