Hello, friends! 👏Welcome to issue #80 of Curiosity > Certainty. I’m Satyajit and all year I’ve loved writing about all things decision-making for you. Well, this is as much for me. I enjoy the process, so I write.

I’ve been thinking about quitting. Not in quitting something specific, like a project or job, but in the idea of it. Like, for example, this time during Diwali when a friend invited us over and we ended up playing Teen Patti, a variant of poker. Now I’ve played poker only a couple of times in my life, the last time several years ago. Which is to say I was a rookie. And I sure did prove it by playing like one.

I didn’t fold enough starting 3-card combinations. And I didn’t fold enough after I had entered the pot (put money in). Bottom line: I generally didn’t quit playing a round on time and I ended up wiping out all that I had.

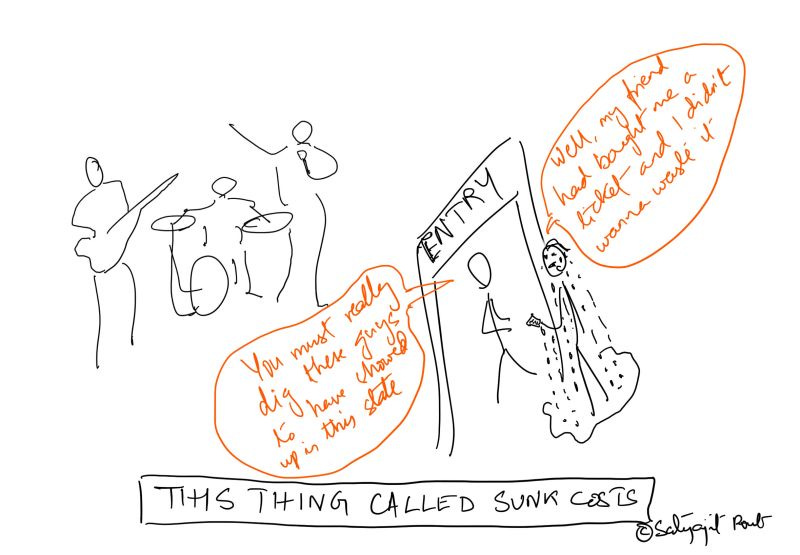

My behavior points to an overarching pattern. Our need for certainty is so pronounced that we would rather continue playing our hand until it became certain we would go broke than fold without knowing for sure that our cards were not all shit. We would take the slimmest chance just to be certain of the consequences, however dire. Why do we feel better staring at certain ruin than if we’re left wondering about what ifs? And how does this tendency play out in life, in business, in high stakes? This week’s issue pulls the curtains back. Let’s go!

The problem with popular advice on grit

You’re level-headed. Your decisions are based on evidence. But what if I told you that the only evidence that you ever get to see is cherry-picked?

Popular advice is loaded on the side of grit. ‘Winners don’t quit, quitters don’t win’ is all you have ever heard. Stories where perseverance saves the day are shared and celebrated. Fattened by such stories, you may be excused for wanting to hang on to lost causes. ‘All your favorite stories,’ your brain screams to you, ‘have a stubborn hero at the heart of it!’

Do you remember that movie where the hero aborts his mission midway, cuts his losses, and lives on to try again maybe? I doubt it because that movie hasn’t been made. The stories where quitting in time saves the day are less told. But that doesn’t make them any less real.

Ask an athlete who has to pull out of an Olympic race only to return in four, eight years to winning glory. Ask a mountaineer who has aborted a once-in-a-lifetime mission and survived to try again, or just survived. Ask a narcotics agent who has had to give up a years-long mission to catch a drug lord because the intel wasn’t confirmatory.

Because we don’t want to be the one who quit too early, we end up quitting too late. Knowing when to quit is not a talent one is born with, or at least one that is permanently set to a default value. It is, like most things in life, learnable. What makes quitting hard? And what makes it easy? Let’s see.

The curious problem of happy teams in sinking businesses

As a leader, you’re in a weird soup. Your team is happy but the business it feeds is thinning. You need to change track given the situation, but you’re worried sick.

You’re afraid pulling the plug will result in loss of your reputation. In fact, you’re so anxious that may happen you’ve even told your spouse about it. In the middle of a funny movie. The memory is fresh: the last time you had called time on an underperforming project, several in your team had quit, confused and betrayed.

You want to avoid that–this is a good crop you’ve groomed. They’ve responded to whatever you’ve asked of them. Put in long hours without flinching. But the ship is sinking. Do you let them push harder or do you change course?

👉Prior investment should not factor in decisions on future investment, when that earlier investment is unsalvageable. That’s the advice on ignoring sunk costs.

What few get is that in the real world continuing to commit to a lost cause is not driven by stubbornness. It is driven by cold fear. No one will trust a leader again if they don’t stick to their word.

So: you decide to stay the course. Your team is happy. They believe in you. And maybe with sheer grit, you hope, you’ll turn the tide in your favor.

This is how you find yourself in the absurd situation of being in charge of a happy team that’s driving a dying business. By happy I don’t mean joyous, but optimistic and trusting given the circumstances.

No, there’s no silver bullet to get you out of this situation when you wake up tomorrow. But there are strategies to put in place early on that’ll cut down the chances of you falling victim to sunk cost bias.

Here’s one I’ve learned from the work of Dr. Jennifer Lerner, Chief Decision Scientist of the US Navy, who runs executive decision programs and has specialized on this topic:

💡Set up decision points ahead of time and contingency plans for them. This is something known as a phase gate approach. It’s your way of saying to your team at kickoff: ‘Three months from now, our goal is to be at this point and if we’re not, here’s the contingency plan for what we’re going to do.’

When that point arrives and you find yourself far out, you’ve the license to change course without fear of team pushback.

Let me add what you should avoid doing. Hide project success factors and use that information symmetry to tell your team that they don’t have the full picture and then push through change without their commitment. That’ll surely get them to mistrust you.

As a leader at work, as the captain of your team, or just among friends, how do you convince people to change course without losing their trust?

How to orchestrate a successful failure

In 2013, when Biogen’s final-stage trial for a drug for the debilitating Gehrig’s disease (aka ALS) failed, thousands of patients were left disappointed. The company's stock dove.

Drug development and biotech are notorious for long cycle times and high costs. With so much invested, it is easy to come up with reasons to not give up. Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos are a case in point.

At the time, Biogen’s head of development treated the team to champagne and an Irish funeral (go check what it is!).

Biogen isn’t alone. Biotech firms have been recently known to drink to failed projects as long as the underlying analytical process is sound. It is the process that merits celebration, regardless of the outcome. (In September 2022, Biogen announced that its ALS drug showed clinical benefits.)

Perhaps Sundar Pichai understood this when he spoke about rewarding effort, not outcomes. He grasped that if outcomes were the only metric, it would make it easier to simply soldier on for a losing cause. Because if they stuck on, they could cling to some hope of turning things around. Quitting guaranteed loss.

💡Leaders do not optimize only for the bottom line. They also think of their reputation. When bottom line meets reputation, you’ll be surprised how often reputation prevails.

Tough times test leadership. It is conceivable that as a leader you may not want to sound flaky when things don’t go well. But there’s a way you can make changing your mind a good thing when reality’s right in your face.

Making failure acceptable as long as the process is sound. Don’t stop at that. Throw a year-end failure party. And let that mindset guide you in the new year.

***

Thank you for reading! If you try any of the shared strategies, let me know your experience. Comments are open, so is my inbox (satyajit.07@gmail.com). Stay well and happy holidays!