#79 - Building a decision bookend and seeing the unseen

Part 2 of primer on mental time travel protocols for better decisions

Hello, friends! Welcome to issue #79 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏 I’m Satyajit and I love writing about all things decision-making.

This week’s issue is a continuation of a class of decision-making protocols that apply mental time travel. If you haven’t already, I suggest you read the first part first, for best results.

Our vision for the future determines our actions in the present. But we see only a sliver of what’s ahead and we don’t know what we don’t know. So how do we decide what to do today that will make our futures better, not worse? Mental time travel is a way to get closer to the answer.

Let’s dive in!

Bookending positive and negative

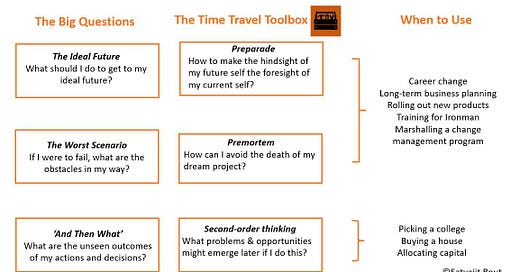

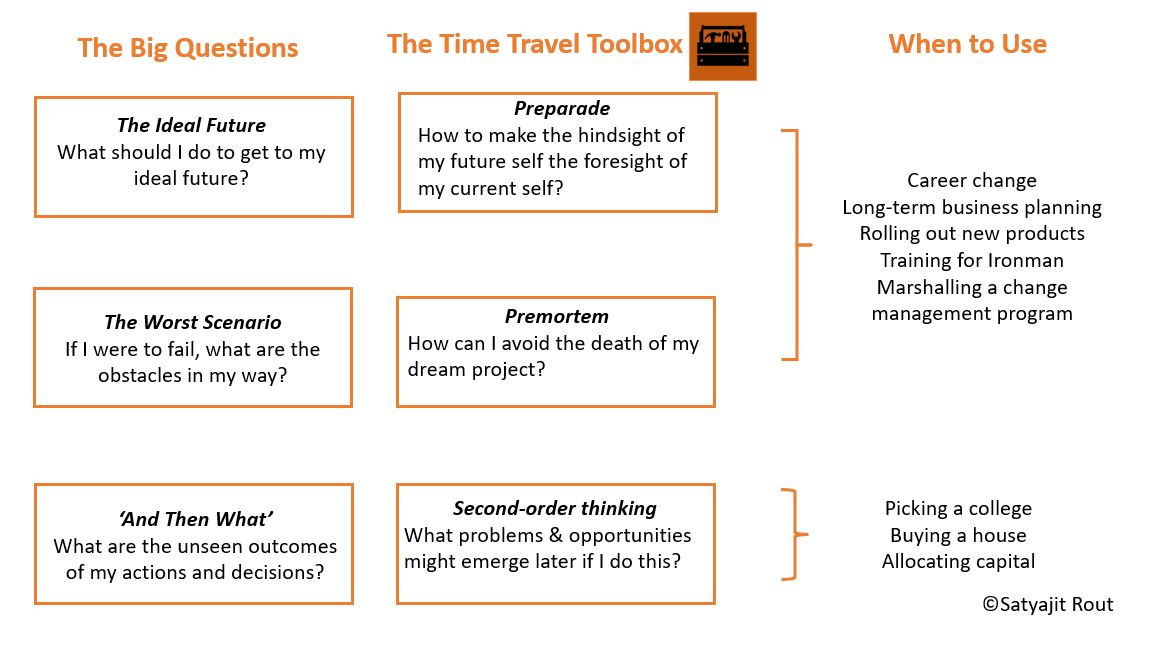

In decision-making, traveling across time from the present moment to multiple futures, both negative and negative, bookends the worst and the best that may happen. Imagining how you got there exhumes what you may have done to have met with abject failure or roaring success, and shows you how to avoid the abyss and shoot for the stars.

How does this happen?

In the present moment you’ve both foresight and hindsight. Foresight sheds some light ahead but that’s not nearly enough to see the path clearly. It means you’re always guessing about your next step. You can’t know for sure until your foot is on the ground and sometimes that’s too late.

Hindsight has the opposite problem. It shows you things with total clarity but all of it has already happened. You cannot change a thing.

Stepping away from the present moment unlocks your thinking from the limitations of currency. It gives you prospective hindsight. It helps you look at the future as if it were the past. That brings clarity. You can now see your path forward by having imagined it backward. Sounds like magic? It almost is. Mental time travel is a signature talent of our species. The problem is we don’t practice it enough.

When you do your time travel, do not just list what you did to get to the future. Also list those things outside your control that could have got you there. Life can be random. Luck can both bring you glory or drive you to ruin. Before that happens, ask: What can I do to improve my chances of catching that lucky break? What’s my plan if we get rotten luck?

And once you’ve done your premortem and your preparade, and you know where you are in the bookended spectrum between success and failure, what you want to do is ask yourself and your group: Do we want to change our minds? Can we do something to get closer to the positive end of the spectrum?

We carefully count what we see. And casually ignore what we do not.

Unlike preparades or premortems, which specifically urge us to visualize negative and positive futures and take steps to prepare for them, second-order thinking just has us asking: ‘And then what?’

By doing that, it makes us imagine the unseen problems and opportunities created by every action we take.

Say you’re early into your career and you want to build your skills and earn more, in that order. You’re debating between staying in your current job and finding a better position elsewhere. Here’s how to apply second-order thinking to make a better career decision.

Look beyond the first available option, no matter how right it feels:

The first answer comes from your reflexive system. It is where your biases rule. So if your ‘heart’ tells you that staying with your current employer feels right, ask why. Is it because you’re comfortable in your team? You’ve built good friendships? Did you feel as comfortable when you were new?

For each option, list down what may happen if it does and does not work out: What will happen if things go well? What will happen if they go poorly?

Instead of doing pros and cons for each option, map the results of each option faring well and poorly in the long term.

For example, the current job going well could mean you learn new skills, work on interesting projects, and get a hike and promotion in the next appraisal. If it went poorly: business priorities change, you play a support role, skill-building is harder.

List down the information you need to decide on the best option:

Once you’ve a map for what may happen if things go well and if they don’t, you can now focus on gathering evidence that will tell you what decision has a better chance of bringing you closer to your core priorities.

In the continue-versus-leave question, your scenario list could point you to the evidence you need to gather. Are you someone with a unique skillset in your team? How fungible may that skillset be elsewhere? What positions or roles does your current skill set leave you out of? What additional skills could expand the employer pool for you?

Asking these second-order questions for a consequential decision is a good first step toward reducing uncertainty. Second-order thinking helps to understand not just the potential opportunities but also the problems that may emerge from your choice.

Second-order thinking for organizational decision-making

When we think of a decision we look at the effect it may have. And then we stop. But the effect has an effect too. Second-order thinking is thinking about the effect of the effect. The need for it becomes clear when you look at how organizations design incentives.

👉First-order thinking (FOT): Procurement setting up 40-page requests for proposals (RFPs) that takes bidders months to meet, and then offering only a snappy decision email to those who miss out

👉FOT: Running an org-wide initiative to come up with a set of values that define the cultural operating system of your organization (example: fail fast and break things)

👉FOT: Recognizing the efforts of employees who fight fires and solve business emergencies

Each of these first-order decisions makes sense. You’re trying to do something right.

Except that when you pause to consider the subsequent effect of these decisions, you may see a different picture. The best vendors start ignoring your RFPs. Your culture isn’t what you imagined it to be. There seem to be a lot of fires around that make execution difficult.

Pairing up first-order thinking with second-order thinking teases out the ripple effect of your decisions. You do so by asking ‘and then what?’

🔑Second-order thinking (SOT): Losing bidders in an opaque RFP often feel disgruntled. So shorter RFPs with transparent decision criteria and assured feedback to bidders for the pain of applying.

🔑SOT: Having a set of values to guide behavior is necessary. But it may not be sufficient if applying them is left to employees’ discretion. Operationalizing values by clear process is a better guarantee of desired culture (example: If your value is ‘fail fast and break things’, reserve a few minutes in every team review to talk about what you broke & what you learned).

🔑SOT: Employees who take charge in a difficult situation are worth their weight in gold. But an unintended consequence of feting fire fighters is that employees may be incentivized to light fires to fight fires. What you want is to prevent fires. What are the incentives you have for fire prevention? What can you do to encourage employees to raise red flags without fear? And what system do you have to receive these signals?

We live in the land of the seen. But what affects our future is often unseen. Ensuring we think of both the seen (first-order) and the unseen (second-order) is what gives us the best chance to execute our plans.

***

Thank you for reading! If you try any of the shared strategies, let me know your experience. Comments are open, so is my inbox (satyajit.07@gmail.com). Stay well!