#77 - When do I go fast? When do I wait?

A primer on decision-making trade-offs between time and accuracy

Hello, friends! Welcome to issue #77 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏 I’m Satyajit and I love learning, practicing, and writing about all things decision-making. I try and keep it actionable so that you can apply it and profit from it. If you find the frameworks and strategies you read here useful, spread the word. You may help someone grappling with a big decision and help this newsletter stand out. This week’s issue maps out the classic decision-making trade-off scenarios between time and accuracy. When do you go fast? When do you wait? What are the action triggers? And to round it off, I share a framework to help you devise solutions that fit the problem. Let’s jump in!

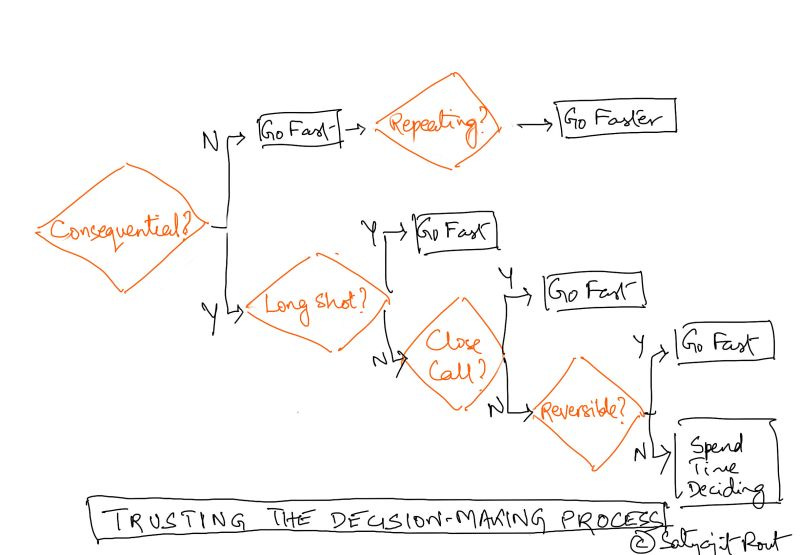

Trusting the process

Don’t waste a knife on a fistfight, and don’t risk your fists in armed combat.

The point of not treating all decisions the same is to use your decision-making time wisely.

Spend time deciding when the stakes are high AND the outcome cannot be reversed. These are choices with deep and lasting impact. Faced with a consequential-irreversible decision, break it down, run small experiments. That way you don’t have to predict what can be known. Thankfully, these decisions are few and far between. You have time to prepare.

Go fast when there’s little to lose OR the outcome can be reversed. Thinking of applying to your dream college? Just do it. Thinking of renting a house? Once you’ve whittled your choices down to a couple and there’s little to separate them, take a pick. Toss a coin if you have to. There’s little difference in downside for your options. But there’s an opportunity cost if you drag your feet. The pull of the status quo is real. Break free when you can.

Go even faster when there’s little to lose and the outcome can be reversed. Curious about a course? Try it. If you don’t like it, you can always take your decision back within the trial period.

Go fastest when there’s little to lose and the decision situation is recurring. Don’t sweat about getting these choices right. Use such situations as practice opportunities to learn more about your preferences and about the world at large.

Trusting this process will save you from decision paralysis, status quo bias, and stress. Make it a habit and you will begin to enjoy the process of making up your mind.

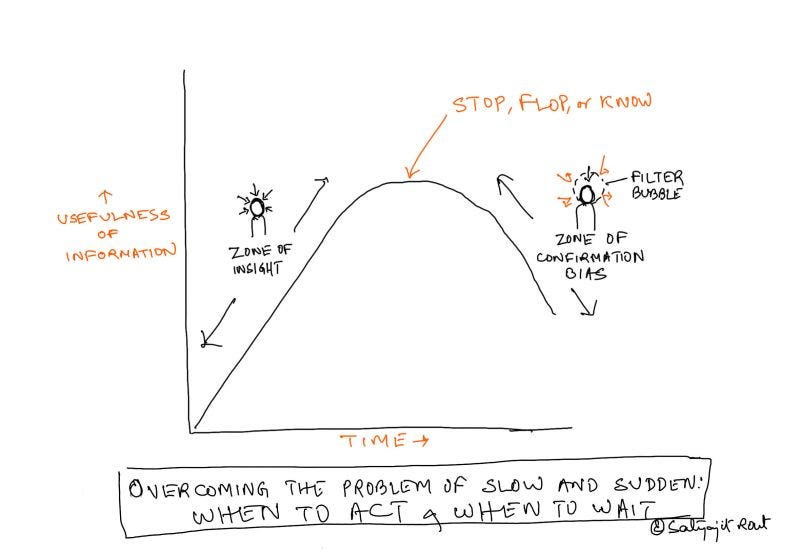

The problem of slow and sudden

Some decision-makers show the symptoms of a disease that I like to call slow and sudden. Patients are known to swing between two extreme states.

For weeks, you see them searching maniacally for perfect information on a high-stakes matter. And then without warning they abruptly stop at some random point and make a knee-jerk decision.

How do you know when to take aim? And when to fire?

I’ve learned a simple shortcut from Farnam Street that helps me time a decision that is consequential and costly to reverse. It’s called STOP, FLOP, or KNOW.

It’s time to decide:

When you STOP gathering useful information

When you First Lose an OPportunity (FLOP)

When you have gathered a piece of evidence that you just KNOW makes the choice clear

STOP

The rate of useful information acquisition flattens out with time. Knowing when it does helps. So that:

👉You don’t waste time building that third prototype or preparing the sixth internal note.

👉You use new information to be more accurate, not more confident.

Picture this: At a late stage, you find something contradictory. It freaks you out. So you dig up more until you find something that falls in line with your going-in view. Then you dig up some more supporting arguments just to restore the balance. You now have a ton of supporting evidence but you also have ignored that one piece of information that could’ve changed your mind.

FLOP

You can afford to wait when you’ve options. But once you start losing optionality, consider yourself warned. Waiting further may mean you’re left with no choice.

KNOW

Sometimes a critical piece of information that you’ve gathered seals your decision. It clarifies all doubts. You may not even be able to say it, like say in a relationship. You just know.

While waiting to make a big decision, you’re trying to reduce uncertainty. You could be obsessed with finding certainty and jump too late, or you could find that process agonizing and jump too early. The disease of the slow and sudden shows both symptoms.

Knowing the markers of STOP, FLOP, and KNOW primes you to look out for them in advance and be ready to jump when the moment arrives.

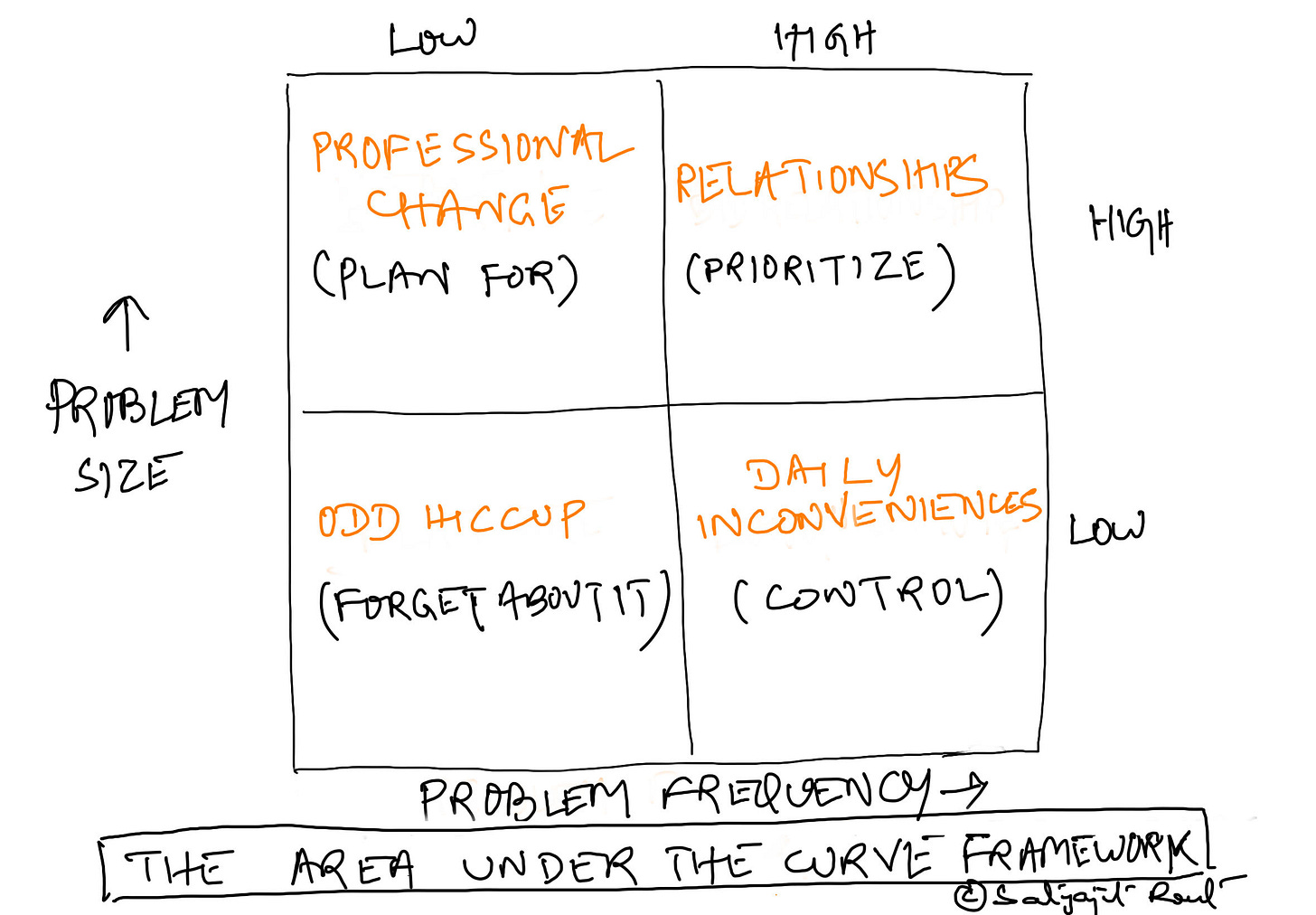

The ‘Area Under the Curve’ framework

All day, every day, you’re being bombarded with problems that need solving. Here’s a simple framework that’ll help put things in perspective so that you don’t lose sleep over an ant bite or ignore a snake bite.

I call it the ‘Area Under the Curve’ framework. It’s got two dimensions–how big a problem is and how often it occurs–and you can use it to rank problems and plan a response.

Imagine a 2X2 matrix with Problem Size and Problem Frequency as the two axes.

Low impact-low frequency: A flat tire

Low impact-high frequency: A long commute

High impact-low frequency: A job change

High impact-high frequency: A bad relationship*

*You don’t get yourself into bad relationships repeatedly but let’s say you’re in one where bad interactions happen time and again.

The bigger the area under the curve, the more attention you need to give it. What’s new here, you may ask. Well, here are typical scenarios where we misread either problem size or frequency.

Underestimate problem size: health. Health is a fat-tailed problem, which means that the bad can be really bad. Yet, the thing that lets health slip under the radar is that the consequences show up much later. Think about chronic diseases and ask if your life is designed to avoid them.

Overestimate problem size: salary. There are several things that determine your happiness at work, but you could focus all your attention on moving this one number up. And even after you get what you want, your reference point will quickly change. You’re keeping up with new Joneses. Your happiness levels off.

If health is a long-term problem that’s short-term invisible, salary is a short-term problem that’s long-term invisible.

Underestimate problem frequency: environment. People visiting Mumbai are often taken aback by the pollution. Locals simply get on, like after a mosquito bite. Yet, what animal kills the most humans every year? The mosquito.

Overestimate problem frequency: terrorism or corruption. It may not be at your doorstep but thanks to media-induced availability bias it’s what you think and talk about disproportionately. Sometimes, it could be the excuse for you to not seek forward motion. ‘What’s the point?’ you may say after half an hour of news.

The AUC framework helps put problems in perspective. Once you plot them by size and frequency, it is easier to know how to tackle them: plan for, prioritize, control, or ignore. What the Area Under the Curve framework does is make you more intentional about how you solve problems.

***

Thank you for reading! Since I got such a roaring response to my funky captions, I’m gonna stick with them. Tell me if you like them (or not 😨). And if you try any of the shared strategies or if you cannot find the image below, write to me. Comments are open, so is my inbox (satyajit.07@gmail.com). Stay well!

I had been previously using the same Farnam Street Pattern to hire junior managers and I'm glad I'd saved your article because it expands the framework to a point where I can use it to train first time managers.