#76 - Say no to decision paralysis

How to behave in a food court, at an ice-cream parlor, and in the throes of a big decision

Hello, friends! Welcome to issue #76 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏 I’m Satyajit and each week I write about all things decision-making. I try and keep it actionable so that you, my reader, can apply it and profit from it.

Decision paralysis is a real thing. It is eerily common and shows itself in our everyday behavior rather colorfully (‘I don’t know what to do! I don’t know what to do! Oh my god, oh my god!’ OR ‘If we do this, then… which is good, but if we do this, could it be better? Or maybe not. Wait, maybe…’) Not all of it is funny. Or rather, it is funny until it happens to you. So, this week is all about protocols to help you get your brain out of that funk when you need it.

Let’s dive in!

Eliminate, then select: the food court problem

You’re at a food court. You’ve gone around the place twice over but you’re no wiser. The tacos look nice… But if you go with tacos, it’s goodbye pizza, ramen... a familiar decision panic is creeping up.

Sometimes, the problem with decisions is that the options are too close to each other. Often, the problem is the opposite: the options are too diverse. We aren’t comparing things of the same kind. So, we’re unable to compare the relative outcomes of choosing one over the other.

If so, it may hurt to go fast on such decisions without taking a basic hygiene step first.

Two mistakes are common in the food-court situation:

1️⃣ We don’t recognize our likes, values, goals.

2️⃣ Because of #1, we spend a lot of time torn between options we may not even care for.

Some housekeeping can nip these in the bud. How?

✔Apply the principle of inversion.

Eliminate first. Ask ‘What’s the worst option?’ and avoid it. Rule out cuisines you dislike. Once you do that, it’s harder to get your order wrong because you’re left with options you similarly value.

Thinking of your next vacation? Find your holiday nightmares.

Pondering a career move? Find that profession that is misaligned with your values/strengths.

Thinking of starting your own business? Don’t just do it because your good friend did it, if the idea doesn’t excite you.

💡No matter how well a bad (= misaligned) choice may turn out, it will never make you happy. Showing extra rigor on options that may not meet your criteria because you haven’t defined them won’t help you. So, weed out categories that don’t meet your brief. Kill the likelihood of the worst payoffs.

Spending time eliminating allows you to escape blunders. Now you’re left with comparable choices in a class of options you more or less like. That’s a good place to start selecting.

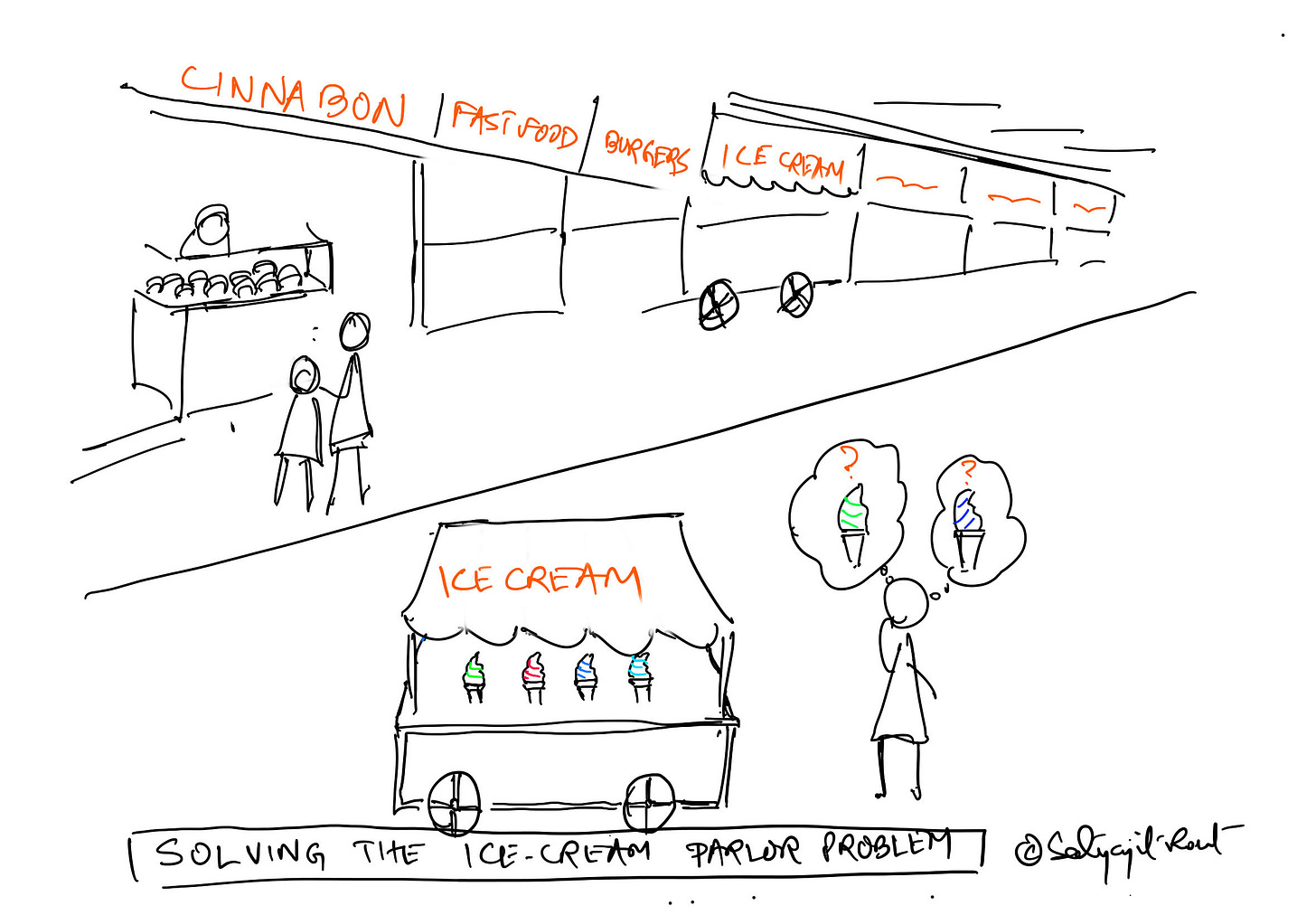

Fear of a better option? The ice-cream parlor problem

So, you’ve skipped past your food-court indecision by eliminating options, and made a beeline for the ice-cream parlor. Nothing makes you happier than a scoop of creamy gelato.

Only, once there, the spread paralyzes you. How do you know which is the right choice?

Sometimes we’re uncomfortable with making a decision when the outcomes are all good and close to each other in payoff. We’ve all smirked at the crisis of that high-achiever batchmate with invites from two top colleges or that colleague with offers from two dream companies 😏 Yet, in a similar situation, we would be just as anxious 😰

This is not a dilemma. In a dilemma, both options are undesirable. What you have is an anti-dilemma. All options are desirable. The problem is that they stack up too close to each other. An anti-dilemma can cause decision paralysis. Even when the choice is between your favorite ice-cream flavors.

Unconvinced? Swap a flavor of ice-cream with boiled cabbage. Does the choice still tear you apart? I doubt.

Here’s how it works in your head. The human brain craves contrast. But when there’s little to separate the expected emotional outcomes from the options at hand, you’ve no reliable metric to go by. Next, you’re splitting hairs.

Annie Duke calls such decisions ‘sheep in wolf’s clothing’ because they seem risky but are not. She suggests you ask yourself a simple question to break the deadlock: ‘Whichever option I choose, how wrong can I be?’

💡If the answer is ‘not much,’ it’s better to go fast because there’s little to gain by being slow and thorough and because it’s impossible to find clinching information short of the actual experience.

🗝We size up all decisions as a time-accuracy tradeoff. In a food court, you can go terribly wrong if you pick a cuisine you have little taste for. At an ice-cream parlor, you can go barely wrong with the flavor if you love ice-cream above all. It makes sense then to spend time eliminating categories (= be accurate) and save time selecting from one (= be quick).

And the way to do that is to toss a coin. What? Yes!

Mathematician and poet Piet Hein wrote a poem A Psychological Tip that tells us exactly how to get ourselves out of a mental bind. Flip a coin and when the coin is spinning mid-air what you wish for is what you should go with.

Stop looking for marginal and impossible-to-know gains and decide fast. Use the time saved to place more bets. These will tell you more about the world and about your own likes and dislikes. That’ll help you with all other decisions at hand. Next time you’re at the ice-cream parlor, toss a coin.

Ain’t no mountain high enough

The opportunity cost of an activity is what you give up for pursuing it. A decision is big if you’re giving up something worthwhile for it.

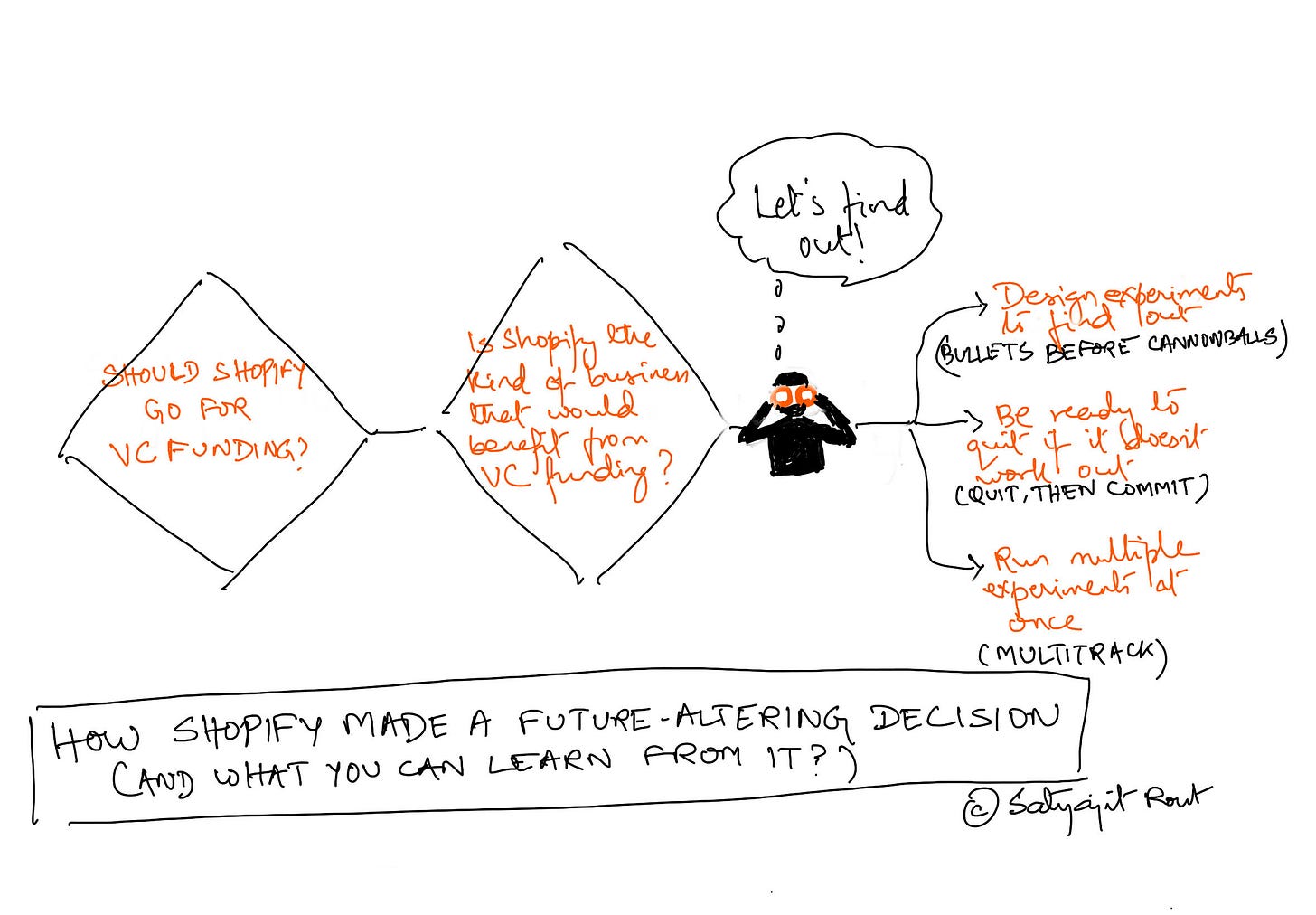

And for consequential-irreversible decisions, we all have to live without what we choose to give up. Even Tobi Lutke, the CEO of Shopify.

Lutke wanted to know if Shopify could be a growth company (one that outperforms the economy). If it was, it needed the kind of muscle that only venture capital could provide. That meant taking other people’s money. Lutke was nervous.

Here’s how Lutke lowered the stakes (= the opportunity cost) for the decision that would alter his and Shopify’s future.

Broke down big into small

Lutke took a big decision (go for VC funding?) and broke it down into lower-impact and easier-to-reverse decisions (find quickly and cheaply if Shopify’s a growth company). He put the $50,000 he had saved to answer the question. The opportunity cost at once shrunk.

Such a decision breakdown is known by several names. Jim Collins calls it ‘shoot bullets before cannonballs’; the Heath brothers call it ‘ooch before you leap’; and Annie Duke calls it ‘decision stacking.’ They all ask the same question: how can you lower the opportunity cost?

It’s the same with dating before marrying, interning before jobbing, trying before buying. A lame date, a poor internship, a shitty rental–you can survive that.

Was ready to quit

Lutke was ready to quit if the results didn’t support his bet. He was clear about not commiting more into the project in the hope of salvaging it.

‘Winners don’t quit’ advice assumes a super high cost of quitting (dropping out of college after an education loan, moving back home after emigrating, divorcing). But once you break down a big decision (Lead Domino), most subsequent decisions have a lower penalty to quit. Pay the penalty if you have to.

Leave that show mid-season, that book mid-page, that date mid-evening.

Multitracked

Breaking down a big bet into a few smaller bets and trying them one by one is good practice. But Lutke amped it up. He took the $50k, split it into five ideas for growth, and funded them all at once. If at least two of them worked, he told himself, Shopfiy was a growth company. All five worked.

One bet can be a fluke but five is a pattern. Bunching multiple bets allows you to be more accurate without losing more time. This is called multitracking.

Want to learn a topic? Start several books on it at once. Want to find someone special? Date a few at once.

We all have to go all in when the time comes. But it’s what we do before that that makes the difference. When our future depends on the outcome of a decision, it’s better to test out options before committing ourselves to one. This needs time, yes, but remember you can save time on the smaller decisions. That’s exactly what this week’s issue of Curiosity > Certainty teaches you.

***

Thank you for reading! I went funky with the captions this time. It was fun! Tell me if you like them (or not 😨). And if you try any of the shared strategies, let me know how that works out for you. I’m all ears for how I can make this newsletter more useful for you. Comments are open, so is my inbox (satyajit.07@gmail.com). Stay well!