#75 - Deciding, fast and slow

A primer on pacing your decisions

Hello, friends—old and new! Welcome to issue #75 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏 I’m Satyajit and each week I write about all things decision-making. I try and keep the advice actionable so that anyone doing knowledge work can apply it and benefit from it.

We are often guilty of spending too much time on the small decisions and not enough on the big ones. Some of it is fear. We don’t want to tackle the big bad problem just yet. Most of it is a lack of differentiation–we treat all decisions the same.

Through a simple system of transfer of time from the small to the big decisions, we can create mental space for the tough decisions. And once we can do that, we must not stop. We can pick up the pace on the everyday choices, not only to get done with them but also to learn a bit more about the world and about ourselves with each turn.

Dive into the heart of deciding, fast and slow.

If the question of how better decision-making can improve your life draws you, hit subscribe!

Deciding slow

Common decision-making advice, even in my favorite book on the subject Decisive, assumes that you, the reader, know which decisions are important to you.

But what if–and this is rather common–you don’t know which decisions you should spend time on? Following sound advice will backfire if you apply it in the wrong context.

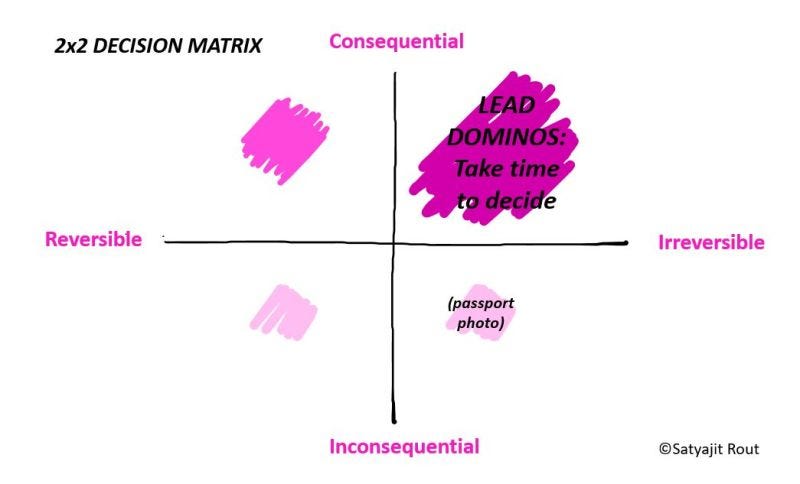

Here’s a simple rule for spotting the kind of decisions you should spend time on. Jeff Bezos calls such decisions one-way doors. Tobi Lutke (Shopify) calls them undoable. Shane Parrish (Farnam Street) calls them irreversible.

Great, but is irreversibility the only check? Nope.

Your passport photo is irreversible. You may look like a dork in it, but perhaps it shouldn’t bother you enough to have you book a studio for a day for it.

So, how do you pick between the passport-photo type and moving-to-a-new-country type of irreversibility?

Track impact. See how much the outcome matters. Will this decision make a meaningful difference to your future and that of your family, your work, your business?

There you have it–your consequential-irreversible decision quadrant. Shane Parrish calls them the Lead Dominos. Give your best to them, for they can change your life.

But you’re already overwhelmed by too many decisions. How do you find the time for your Lead Dominos? Steal it from the time for all other decisions.

For other decisions–and this is the second trick–you gotta learn to play fast without being loose.

How? We’ll get to that in time. For now, pull out a piece of paper and write down your Lead Dominos. They should only be a few but they make all other decisions irrelevant. Are you spending time on them?

How to go fast (without being loose)

For you to pull off the decision-prioritization trick of champion CEOs and business leaders, you need to know how to balance speed with precision. You already know how to be precise with the biggest decisions (link in comments). Now’s the time to teach yourself to be fast without being loose.

You always want to get the most bang for your time. The smaller the impact of a decision, the lesser is the value of your time spent on it. Adjust suitably.

Here’s how to make that happen.

✔Delegate

This is no cop-out. Delegation has got a bad rep. Let’s clear that first. Delegation doesn’t mean offloading work so that you can enjoy two-hour lunches. Delegation is trusting someone, often a team member, with a task so that you’re free to operate in your highest-impact zone, which should be your irreversible-consequential decision box.

Now, delegating well means you assign the decision to someone for whom it is the most consequential and/or who’s the domain expert for it. In other words, delegate to offer someone else the chance to operate in their highest-impact zone. This will hone their decision-making skill without weakening the quality of the decision.

Hat tip: Delegate but do not forget. Do check-ins. Stay on top. You don’t want to have to clean up afterward because you washed your hands off the matter too early.

✔Do the Happiness Test

Sometimes there’s no one to delegate to. Such situations call for Annie Duke’s Happiness Test. You use this test to find and make decisions that are less consequential or are reversible.

Thinking of happiness as a proxy for quality of life, ask yourself: What’s the penalty for not getting this decision just right? Will it meaningfully affect my happiness a year from now? A month from now? A week from now?

The shorter the time for which the decision will matter, the less you should sweat on it.

Patrick Collison, CEO of Stripe, when asked about the biggest difference in his decision-making in the last five years, said that today’s Patrick has learned to ‘make more decisions with less confidence but in significantly less time.’

Know that there can only be a few consequential-irreversible decisions on your plate at any time. For most other decisions, the payoff for getting it just right flattens with time invested. So, why not look to save time on them?

⚠A word of caution: For those of you making decisions at the org level, understand the kind of organization you work in. At a big FMCG, launching a new product may take a couple of years; at a tech startup, that may be a couple of months. This time frame for decision-making is called Buxton Index (link in comments). Whatever be the Buxton Index, acting quickly for anything other than your Lead Dominos is a good habit. Practice it.

And once you’ve learned to gather some speed when the stakes are lower, there are ways to go even faster and save even more time for the choices that matter most to you.

How to make a molehill out of your mountain

What is a mountain to you could be a molehill for someone else. Your biggest decision could be someone’s choice for dinner.

Andrew Wilkinson’s VC firm Tiny Capital owns 40-odd businesses today. Once he made a poor decision. He decided to take on VC-backed project management software Asana with his bootstrapped Flow. He bled 10 million dollars in no time. For most, this would’ve meant death. Not for Andrew. Why?

As a multiple-business owner, he knew he would have more cracks at the same kind of problem.

Andrew taught himself to make investment decisions as kids teach themselves electricity. His approach was to ‘take forks and stick them in electrical sockets, and then we learn and we start calibrating.’ With every repeating choice, he learned something new for the next time.

This is exactly what you can look to emulate.

Pick the class of decisions that present themselves to you again and again and are low-impact (molehill to you). Annie Duke calls such decisions repeating options.

Two of my repeating options from earlier in my career: running meetings effectively and how to make my emails easier to respond to.

Today, I follow a tested process for both that has emerged from previous trials. Because of it, not only are my meeting routine and email subject-line format no-brainers now, my current repeating option is bigger–how to drive change across business functions.

Taking long shots is another way to juice out time and knowledge for future use. Long shots remind us of the ‘if you don’t ask, the answer is always no’ principle. But we’re often scared to take a punt because of the momentary egg on our face.

Long-shot makers are not regular optimists. The optimists tend to hope for better luck, while the long-shot makers brew their own luck. They are as Stephen Dubner, co-author of Freakonomics, says ‘active participants in trying to make good things happen’ for themselves.

Because long shots have a lot to teach you at no cost, when faced with any such decision, you should just do it. Send that application, that cold email, that pitch. You’ve nothing to lose.

In summary, take the template of repeating options and long shots and apply it wherever you can. You’ll learn from the iterations until you’re skilled enough to be climbing a mountain a day.

***

Thank you for reading! If you try any of the shared strategies, I would love to know how that works out for you. Also, please tell me how I can make this newsletter more useful for you. Comments are open, so is my inbox (satyajit.07@gmail.com). Stay well!