Hello, all—old and new friends! Welcome to issue #74 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏

This week’s issue dives into how we build and protect our system of beliefs, how we overvalue the inside view and ignore the outside view, how perfect information does not guarantee a perfect outcome, and how the stories we tell ourselves can be misleading.

Dig in if you want to make an honest self-assessment and build on from that.

I’m in a weird relationship with facts. They don’t seem to help me.

You believe that only if you had the right information you would make all the right decisions.

You scour for information, you talk to people. you try and make an ‘informed decision.’ Still, you’re often surprised by how things turn out.

What’s worse, the harder you work, the more you seem to be caught wrong-footed.

💡Here’s a secret: The problem has less to do with information. It’s got to do with you. Your beliefs.

Our beliefs are our map of the world into which we fit all information.

👉We are known to cherry-pick information that fits our map–confirmation bias.

👉We reject information that questions our map by putting it through a stricter check–disconfirmation bias.

The more information we process, the more cherry-picking we do and the more convinced we get that our map is indeed the territory.

You see the problem? Hang on, that’s not all.

Apart from cherry-picking, we suffer from a problem of cherry-spotting.

👉We have an eye for more recent information–recency bias.

👉We play up more vivid information in our map–availability bias.

In the grip of confirmation bias, when we see something vivid that fits our map, our brain shouts to us: ‘Not only is what I believe true but now I also have this beautiful example to prove that it’s true.’

What do we do?

First, let’s change the metaphor we use for our brain. Our brains are not computers that all churn out the same output for the same input. Robert Burton, author of On Being Certain, likens our brains to deep learning models that produce different results depending on what they have been fed (experiences, preferences, mood).

How do we make our beliefs coincide with reality?

You can’t, not completely. Cognitive biases are like zero error. They’re consistent. But you can reduce the size of the error. You can bring your beliefs closer to reality.

✔Take the outside view. The outside view has maps of other people. It is not a reflection of the beliefs of any one person. So, if you can triangulate a location across other maps, then it’s more likely to be correct than if it exists only in your map.

Your map feels precious to you because it’s an accurate model of your beliefs. But your beliefs are not the truth. No matter what you say.

You’re unique. You’re also overconfident.

In a 1976 survey in the US, high-school students were asked to self-assess on a bunch of things: friendliness, leadership, sports.

85% believed they were friendlier than average; 70% thought they were better leaders than average; and 60% saw themselves as above par in sports.

The survey was followed by actual tests and, wonder of wonders, the least capable students showed the widest gap between perceived and tested abilities.

You’re thinking, I can’t imagine how red those faces must’ve gone when they were shown the results. Umm… not quite. The students simply dismissed their failings as inconsequential.

💡Not only do we think too much of ourselves, our low ability has the effect of making us more optimistic about our chances. And even when challenged with the grim truth about our ability, we brush it off as immaterial.

There it is, the problem: We’re too quick to make up our minds and too slow to change them.

These studies were done on high school students. Do these tendencies show themselves beyond this demographic? Let’s look at the evidence.

Actively managed mutual funds tend to give poorer returns than index funds over time, more than 70% acquisitions do not create value for the acquirer, we believe our marriage is unbreakable, our restaurant will do roaring business, our projects will not overrun in cost or time, and so on.

These situations are so common that a name exists for their solution: reference class forecasting. The solution is simple, if not always easy:

1️⃣Find a matching reference class–a group of situations that matches yours.

2️⃣Find the base rate–the historical average of the metric you’re looking for. This is the outside view to your inside view.

Hat tip 💡: Also look at the distribution of values. The more closely gathered the values are, the more you can go by them.

3️⃣Adjust your prediction by taking into account the base rate.

More often than not, others have been in your situation. You can learn from them, instead of ignoring their cases as irrelevant and reading too much into the uniqueness of your own situation.

The problem with being smart

Smart people are good at convincing. I don’t just mean convincing others. I mean convincing themselves.

Smart folks are more likely to believe in their stories as the final truth. The more they believe their stories without question, the bigger is their blind spot. The blindness amps up their confidence, makes them live in an illusion.

Illusion of superiority - ‘I’m better than the rest.’

Illusion of control - ‘I’ve got everything covered.’

Illusion of validity - ‘I predict better than any process.’

This amplifies their biases and undermines the need for correction. Result? Smart people tell themselves they don’t need more time, an outside view, another option, or even luck.

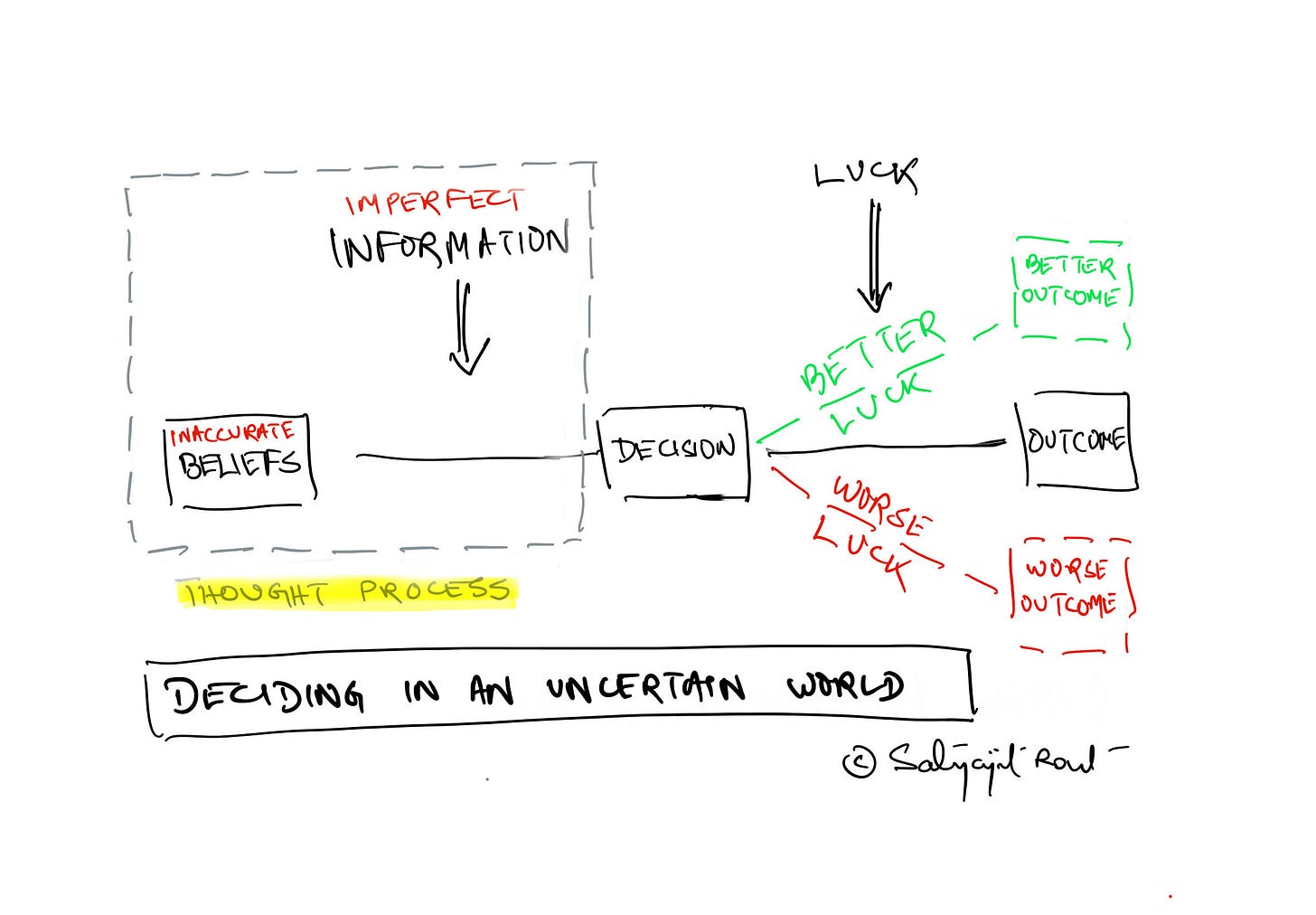

Our thought process consists of two components–the input we have and the filter through which we view it. The two are tied at the hip. Often we don’t have perfect information. Too often, our beliefs distort how we see reality.

Until we’ve made the decision, we’re in control. Once we’ve made it, we have no over the outcome. Better decision-making is all about isolating the outcome (or luck) from the thinking and continually refining the thinking.

Say a smart friend of yours is considering opening a restaurant. You ask her about her odds of making it (base rate)–what percentage of restaurants in your city (reference class) shut down in the first year? I don’t know, she says. She then tells you she’s mapped out all possibilities and, given her staff quality and unique decor, you would be a fool to not bet on her. Your outside view reminds her that it’s her first stint in the restaurant business, more than 75% restaurants close within the first year, and the rentals in her pincode are in the top 10% in the city. She smiles and tells you that those numbers are for others less prepared.

You see where being smart may make things worse?

Because smart folks have honed the ability to spin compelling narratives in their heads, they are less bothered by the quantity or quality of input. And their illusions about themselves infect the thought process.

How to identify such smart folks?

They tend to say ‘Didn’t I tell you this would happen?’ or not say ‘I don’t know’

They appear confident in uncertainty and make you wonder how

Their stories are too coherent and simplistic

They assign luck a role as it suits them

They respond to feedback with a story

Critical thinking is not the same as smartness. Critical thinking allows for healthy doubt in what we consider to be true about the world, whereas smartness is linked to a quicker thought process. A critical thinker marks a win in their book when the thinking is airtight; a smart one pulls out a suitable story for the occasion, depending on the outcome.

What do you want to be?

***

Thank you for reading! If you try any of the shared strategies, I would love to know how that works out for you. Also, let me know how I can make this newsletter more useful for you. Comments are open, so is my inbox (satyajit.07@gmail.com). Stay well!