Hello, readers! Welcome to issue #72 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏

Not many people know that Daniel Kahneman’s Nobel-Prize-winning ‘prospect theory’ was not always called that. Kahneman and long-time collaborator Tversky actually called it value theory.

In Kahneman’s words, they changed the name because the term ‘value theory was misleading, and we decided to have a completely meaningless term, which would become meaningful if by some lucky break the theory became important. “Prospect” fitted the bill.’

Scott Adams has a similar reason for Dilbert. Dilbert is an odd name. And without a surname to go with. Adams has a Kahneman-esque reason for that. In his words: ‘Any name you give him, somebody’s going to be a hater. So you’re taking people out of the equation as soon as you name him. Maybe it’s a name they’ve heard of. There’s a reason why it’s Dilbert and not Bob, you know?’

In both examples, the creators came up with names that worked around any pre-existing associations that may have distorted the intended meaning of their idea–be it a concept like prospect theory or a comic character like Dilbert.

Yet, sometimes, you want to suggest an association. This newsletter has the words curiosity and certainty arranged a certain way on either side of a mathematical operator because I don’t imagine myself being interested in a relationship different than that.

So, keep the door open if you don’t know the future. Close it shut if you’re sure of what you can’t let out.

Why pros and cons will fail you

Almost always the first, and often the last, decision-making tool that you will pick up is one that will fail you miserably.

That tool is the good old pros and cons list.

I’ve seen long-term org decisions being made on the basis of a pros and cons list. And I’ve tried to emulate what I’ve seen by faithfully listing pros and cons to make a choice.

But that’s like squeezing a lemon harder to get honey.

Here are what pros and cons won’t tell you.

❌How bad can bad be, or how good can good be (payoff)

For a VC making an investment decision, the upside is way bigger than the downside–something that a pros and cons list won’t reveal.

❌What’s the likelihood of bad or good (probability)

For a manager making a hiring decision, a competent hire can be a risky choice if their record suggests they’re likely to leave in 6 months.

❌What is most important to you (preference)

For your choice of holiday, the rains can be both a blessing and a curse. If you want to lock yourself up to catch up on your reading, rains are your best friend to keep you in. If you want a week of sightseeing, rains are your worst enemy.

A pros and cons list is better than nothing the way a hammer is better than your fingers. But as the saying goes, ‘To a man with a hammer, a screw is a defective nail.’

Hammering means you’ll break things often. Don’t just walk around with a hammer. Get a toolkit for yourself. A good decision-making toolkit should care for about what Annie Duke calls the three P’s: payoff (how much you’re getting), probability (how likely it is), and preference (what’s most important to you).

How to build a decision tree

Say you’re considering treatment options for a health problem. The problem is elective now, which is why you can either manage it conservatively until it worsens irreversibly or you can choose one of two surgical options.

How would you decide?

The path to genius avoids stupid. So first: what’s a bad way to decide? Going with pros and cons is a poor choice. Link to why I think so in comments.

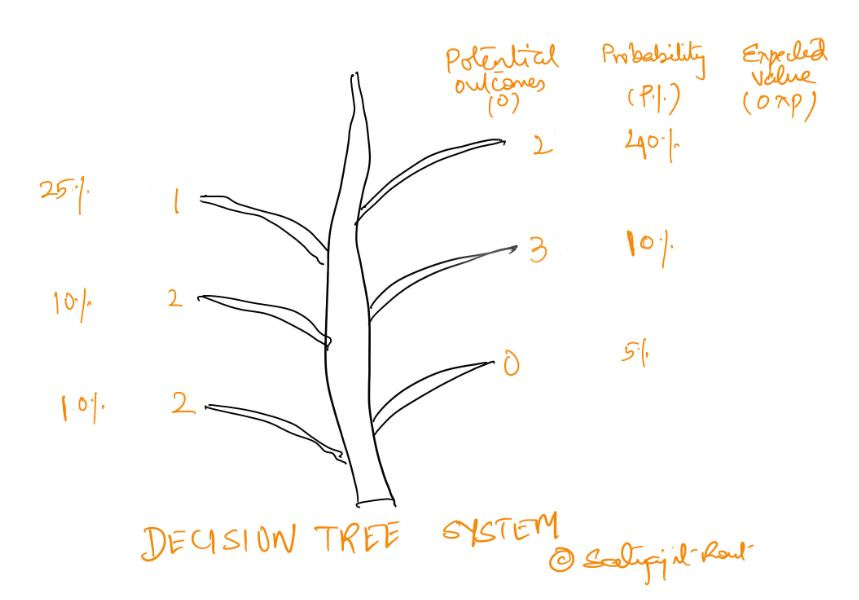

A good way to approach your medical dilemma would be to build a decision tree. For every decision option, a number of different outcomes are possible. Some we look forward to, some not. Some more likely, others less so. A decision tree helps you gather these variables into an expected total value for each option and then compare the relative values among all.

Approach the decision in the following order:

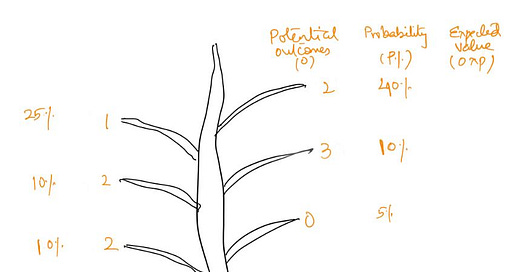

1️⃣Take an option (say, conservative management) and list all potential outcomes for it.

2️⃣List payoff for each outcome based on your preference. Decide preference by splitting 10 bucks among all outcomes, in unit increments of 1 (shown as potential outcomes in the image below). Which means all payoffs should add up to 10. This also limits your list of outcomes to a reasonable number.

3️⃣List probability of occurrence of the outcomes. Express probability in percentage, not words (unlikely, rarely, often, etc.) because people understand them differently and you may want the opinion of your spouse or family on this decision. Total probability should add up to 100%.

4️⃣Get expected value for each outcome by multiplying payoff and probability. Add up all expected values to get the total value for the decision option. Remember the maximum total value is 10 so if you get a bigger number, something’s off in your math.

5️⃣Repeat steps 1-4 for the next option (surgery option 1).

6️⃣Compare the values for all options and pick the best one.

Knowing how something works means knowing when it doesn’t work. A decision tree has its limitations. Real-life (that includes business!) problems are not always clear cut. In one or more of payoff, probability, and preference.

If you’re mulling over greenlighting a development budget for a new product, your choice of outcomes may depend on estimates of the market demand, which can cover a big gradient. Plus what your competitors are planning to do. So you can’t really say how likely something is.

Or say you’re looking for a spouse. You may not even be able to imagine the list of reasonably possible outcomes.

That said, decision trees work well when you have time and when you don’t have to think of second-/third-/fourth-order consequences.

For trickier problems, which I will define in the coming weeks, there are other ways to decide.

Living by a ‘free returns’ philosophy

We spend too much time chewing on decisions that we can spit out.

We crave certainty. We crave more information, even to buy a pair of shoes. But we may not. Spend less time trying to make the right decision and more time actually trying things out. Because if it doesn’t work out, you can always take it back. This is what I call a ‘free returns philosophy’.

The mistake we make is that we think we need to know more about what’s out there in the world. We don’t. We need to know more about ourselves, about what’s inside of us for the world out there. The best way to know ourselves better is to make more choices.

Because no matter what you say no to, someone would’ve said a yes to and would’ve made it work. So quit looking for more information. Quick reading through more shoe reviews. Go ahead and make a choice. Try it on. If it fits, great, If not, move on.

Not every choice needs to be a long-term commitment. But every choice will tell you something more about you. The world will give you feedback and your response to that will tell you something about yourself. That’s the true upside of having a free returns philosophy in life.

***

Thank you for your time! If you try any of the shared strategies, I would love to know how that works out for you. And finally, let me know how I can make this newsletter more useful for you. Comments are open, so is my inbox (satyajit.07@gmail.com). Stay well!