#67 - What they don't teach you at school about decision-making

Plus: How Shopify CEO tests system resilience and the difference between experience and intuition

Hello, dear readers! Welcome to issue #67 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏

This is the longest issue I’ve compiled in a while. It takes a single subject—how to become a better intuitive decision-maker—and examines it from a bunch of angles: common myths, practices for self-improvement, and when to accept humility. Read on…

The first lie about decision-making

Some time ago, to my question of how he made big decisions, my then boss and CEO had said he follows his gut.

My jaw had hit the floor. The CEO of the company decides by gut! And here I was hoping for a time-honored process, the recipe to which would be worth an arm and a leg.

I was wrong. He was right.

Classical decision-making has a recipe: Collect all information you need, follow a prescribed process, and it’s very likely that you’ll reach the same conclusion as your CEO, or Einstein.

That’s how you buy a car, a TV, a laptop. Information is:

✔Available

✔Reliable (unchanging with time)

✔Objective

You’ve the luxury of time (tomorrow is the same as today) and inexperience (high level of certainty makes experience surplus to need).

But a CEO does not get paid to decide on the right car or TV or laptop. She gets paid for capital allocation. Where to put money? Which bets to make?

I experienced this while working on investment decisions, where information is:

❓Missing

❓Unreliable (changes with time)

❓Subjective (how do you judge the character of a founder?)

Enter: trade-offs. Could you give up accuracy for speed? What steps can you skip? How much uncertainty can you bear? These become the new big questions.

If you’ve only learned the neat classical process at decision-making school, you’re in for a shock.

A line cook knows the dish needs tomatoes at a certain temperature. The chef knows what to do when it gets too hot or cold, or the pantry’s out of tomatoes.

This is called gut. Aka experience, judgment, intuition.

(Experience is not the same as intuition but for simplicity we can assume so).

Experience means you’ve been in such a situation before, and learned. You can spot past patterns in what you’re trying to solve today.

The hardest decisions are made under uncertainty. There are no set options to pick from, only a set of possibilities. This is called naturalistic decision-making.

Classical decision-making will help you buy your car, laptop, or even house. Anyone can build this skill as long as they can measure and compare and they’re trained in the process.

But building naturalistic decision-making skills will make you rare and valuable. This is what CEOs are paid for, military commanders are trusted for, and MS Dhoni is idolized for.

A brainful of myths about intuitive decision-making

🚫It’s intuitive, so it can’t be taught and you can’t get better at it

The classic ‘You either have it, or you don’t’. Goes hand in hand with ‘leaders are born, not made’. Ever heard of tactical decision games in the military? Even strategy video games can build decision-making muscle by putting you in certain types of situations where you learn to make trade-offs–something that Tobi Lütke, Shopify CEO, believes ‘teach you complex system decision making in a way that not much else can’.

🚫It’s intuitive, so it can’t be explained.

I’ve seen decision-makers who’re better at making decisions than they’re at communicating. It’s plausible to hear them and wonder if they’re winging it. Truth is that not everyone’s a polished communicator or teacher.

🚫It needs a foundation of analytical decision-making.

The difference between intuitive and analytical is what separates art from science. Art cannot be as precise or formulaic as science is, but it isn’t irrational either. Major John F Schmitt, author of several books on tactical decision games in the US Marine Corps, describes intuitive decision-making as arational (beyond reason but not against reason).

🚫There’s always one perfect solution, even with intuitive decisions.

It is hard to run counterfactuals when you’re going into war or picking a partner. What would the alternative be? How many can you map out?

Any complex system has multiple interconnections. How these interactions happen determine the outcome, often manifest in a wide range. To quote General Patton, ‘There is no approved solution to any tactical situation’.

🚫Intuitive and analytical decision-making are mutually exclusive.

No one is completely scientific or artistic. No meaningful decision is completely intuitive (house, job, career, investment). It’s always some combination of intuition and analysis that’s at work in a given situation.

🚫Data is always above intuition

Say, a company makes a song and dance about its 1:1 gender ratio. Is that company perfectly gender-inclusive? What about average pay across gender cohorts? Average hike? Happiness score?

Data could suffer from a number of problems–survivorship bias, framing, handpicking. Intuition and data do not have to be at loggerheads. More data is good, but context is important. An intuitive decision-maker is a good student of context.

A great piece from Glenn Kelman, Redfin CEO, on how not to use data as a crutch to not develop your merchant sensibility.

The value of experts

Experts are useful but they work best in a narrow set of circumstances. Where do they work and where don’t they?

Let me illustrate with a 2X2 matrix adapted from the book Think Twice. Consider:

Range of outcomes along the x-axis (from narrow to wide)

Decision along the y-axis (from rules-based to probabilistic)

A rules-based decision with a narrow range of outcomes could be a simple medical diagnosis. Based on an X-ray or a biomarker. An expert has domain knowledge, but a machine, if fed enough good data, can predict the outcome more accurately than any expert. Machine is best.

A rules-based decision with a wide range of outcomes is more challenging to get right. Chess offers several possible board positions and determining which one is best requires expertise (= the ability to retrieve from stored patterns and make a match). Still, enough data and processing power got Deep Blue over the human line. Expert + Machines are best.

As information goes missing and/or complexity of the system being analyzed increases, rule-based answers become a luxury. Both man and machine need help.

A probabilistic solution with a narrow range of outcomes means that several answers are possible and all can be identified. Imagine formulating company strategy for the next year. Your variables could be last year’s business performance, leading market trends, competitors, customer feedback, funds available, et cetera. Your game plan is based on your unique knowledge of the company. This directs your intuition. Computers can boost your predictive accuracy with data. Expert + Machines work best.

A probabilistic solution with a wide range of outcomes means that several answers are possible but not all can be identified. No one can predict stock market movements, geopolitical relationships, or supermarket sales. No one person’s a domain expert. These are complex systems where consequences of component interactions are impossible to predict. Here, wisdom of the crowd rules.

Why do non-expert collectives tend to do better than the best individual expert? Because their individual error is compensated for by their prediction diversity. This works only if there’s diversity in the crowd.

So what can we do to correct our over-reliance on experts and under-reliance on computers and crowds?

✔Properly classify the problem - don’t have a default approach for all problems

✔Adopt technology - use machine power where possible

✔Seek diversity - reduce blind spots in individual-led decision-making

We still need experts: to make the very systems that will help them decide, to troubleshoot, and to deal with people. And experts are good at eliminating bad options and often that’s good enough.

But most tellingly, experts offer psychological safety. We feel more at ease placing our trust in a high-paid professional with years under their belt than in a nameless and faceless computer or collective. We’re human after all.

The difference between experience and intuition

I cannot explain to you the difference between experience and intuition any better than the late spin wizard Shane Warne did.

He once said of Monty Panesar, a fellow spinner, that Monty didn’t play 30 tests. Instead he played the same test 30 times.

The observation was as astute as it was uncharitable perhaps. But what did Warne mean?

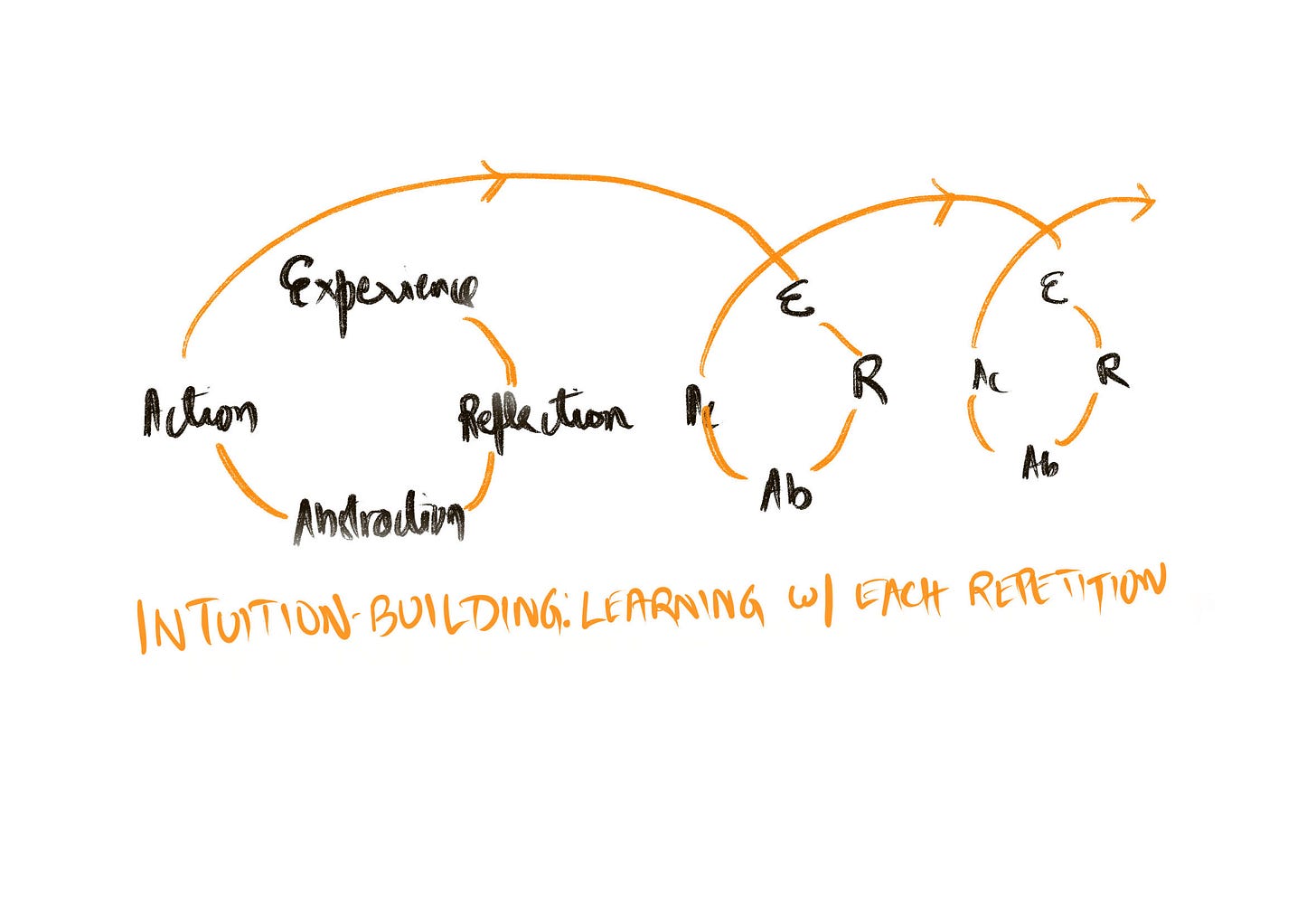

Just notching up experiences counts for a lot less if we’re approaching every problem as if for the first time. Our backlist of experiences has to count for something. It has to help us make fewer mistakes.

The best way to not repeat mistakes is to learn from each repetition. From each turn of the wheel.

Pick each experience apart by questioning assumptions (reflection), build/update a model of reality with deliberate effort (abstraction), and then put that lesson into practice (action) that leads to the next experience to learn from.

When we reflect and store the remnant of an experience in our brains, we’re filing away a pattern (new model of reality). Later, we’re subconsciously matching that pattern with what we see. With the best, the pattern-matching is associative (similar). Not direct (same).

Intuition is nothing but, as Farnam Street calls it, ‘subconscious pattern matching, honed over weeks, years, and decades’.

How to turn experience into intuition

👉Run experiments all the time, not only when you have to.

Shopify does something called the Tobi test, named after a practice started by their CEO Tobi Lutke who would ‘just log in and shut down various servers’ to see if the system had resiliency.

Years later, it was perhaps this habit that gave Shopify confidence to do what they did when they were 600-odd and out of a lease and with a new office a month or so away. They didn’t look for a new lease. They switched to working from home. This was way before COVID.

The smart ones never waste a failure. The best ones never waste a success either. They learn no matter what.

👉Be ready to lose battles if doing so improves your chances of winning the war.

As a young and ambitious professional, you want to impress peers and superiors. So you bury your weaknesses and bare your strengths. With time, you get better at what you’re good at in a narrow way. You become a one-trick pony.

👉Design your life such that you’re forced to reflect upon your decisions.

This is classic habit-building. Make rules that encourage deliberate thought: maintain a decision journal; do after action reviews; run pre-mortems (link in comments). These habits may seem hard to start with, but they’re smart to stick with.

What tiny habit do you have to learn better from experience? Share your method.

The second lie about decision-making…

…is that if you know how to decide in uncertainty (that is, you’ve intuitive decision-making skills), you will do so.

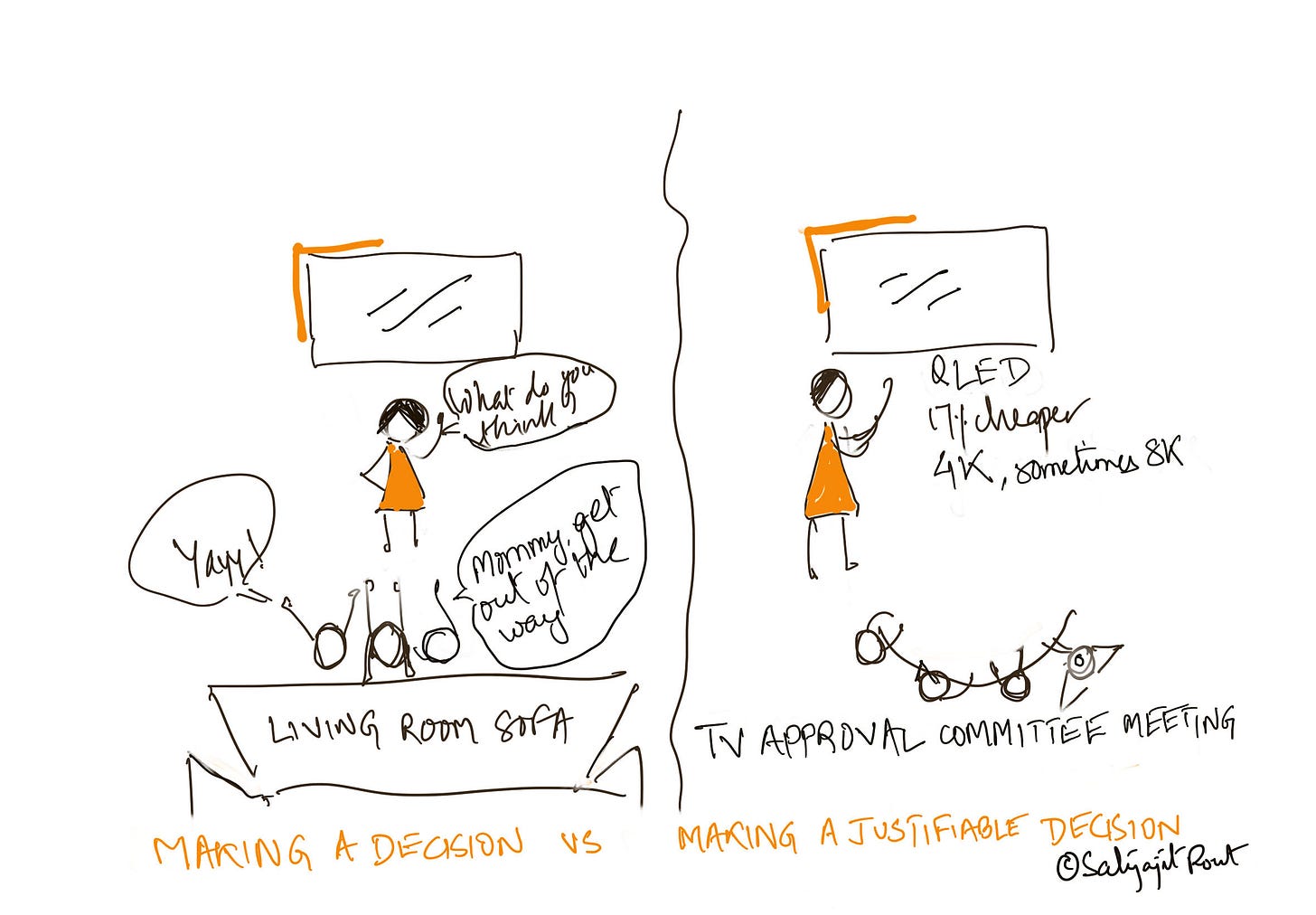

At your job, there’s a big difference between making a decision under uncertainty and making a decision under uncertainty that is justifiable to a group.

The signature of the classical decision-making process is that it is a recipe–it is predictable, followable, systematic. You can document it, explain it to anyone, email it to the board. This feature is a butt-cover. It protects your ass from getting kicked.

But making a judgment call when your job’s on the line or business is not doing well? Many would check their VRS plan instead.

This is where psychological safety helps. Without it, employees land hard or, worse, do not jump.

For decades, how high high-jumpers could leap depended on how stably they could land after. Because they had to jump on to sand pits and sand pits meant heavy landings. Foam matting changed that. By helping cushion landings, they led to a wave of innovation in professional high-jumping. Techniques changed, better results arrived.

Corporates champion meritocracy in the workplace. They say: “Only your talent determines how you shall be rewarded.” But in egging employees to reach for the stars, think of how you can make them land safely. Because in reaching for the stars, they have to first push to the point of failure. And learn from it.

If it’s a myth that just having the ability to wade through uncertainty and make decisions will mean that people will choose to use that muscle, it is hardly a secret that empowering those same people will get them to perform at their best.

***

Thank you for reading! I would love to how I can make this newsletter more useful for you. Let me know in the comments or write to me at satyajit.07@gmail.com. Stay well!