Hello, dear readers! Welcome to issue #64 of Curiosity > Certainty 👏

Often in life you go through experiences as a professional and as a person and you reflect upon them from time to time. But the blackbox remains locked. And then somehow, along comes a book or a blogpost or a podcast or a remark from a friend, and—voila!—the key drops into your lap. That’s the feeling that cohabits with me as I read books on mimetic desire and Adlerian psychology.

This week I offer you nuggets on managing interpersonal issues as a people leader and spotting patterns in yourself. I top it off with why plea bargains are so popular in lawsuits (at least in TV shows). Happy reading!

It’s not your team. It’s you.

Managers, young and old, find resolving interpersonal issues tough.

When it comes to issues between people, your fear as a manager in getting to the bottom of the matter is powerful. That, I believe, is because you’re afraid of what you may discover about yourself.

The last line sounds like it’s from a Disney movie. Let me explain what I mean.

Interpersonal issues crop up because your team is operating by their own hierarchy of values–each different, each a unique North Star to its follower.

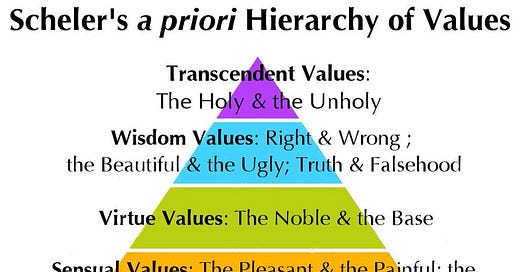

What is a hierarchy of values (HoV)?

Let me define it by pointing to its absence. As Luke Burgis, author of the wonderful book Wanting, describes, the absence of HoV creates ‘a world in which all values are treated as equally important, or where it’s not clear what is foundational and what is not.’

Your team is confused because you’ve not given them a shared HoV. In doubt, they go back to their own hierarchy. They make tough choices about what to do or prioritize on their own. And they wonder why others don’t understand them. Conflict brews.

The manager you only sees the resulting crisis. You begin to believe that your reportees’ interests are at loggerheads. You may go on to reframe it as a personality issue. ‘Maybe you should think about clearing the air with so-and-so’. When you do this, you sow the seeds of doubt in the report. You’ve asked her to operate outside her own HoV without giving her anything to lean on.

She’s now wondering if she’s hard to work with.

At the same time, you craft an internal narrative to justify your response. ‘Only if my team learned to work together…’ you wish for yourself.

What will have your team work well together? A map and a compass.

Map is the terrain of their responsibilities. Compass is the HoV that helps them cross the terrain.

I’ve seen managers and leaders without an HoV talk up case-by-case basis. Case-by-case will not solve the problem of no HoV. In the absence of a guiding framework, you’ll end up copying what you see around you. This is mimesis. It means, left to yourself, you don’t know what you want.

Sometime back, I had asked a reportee about what being a woman was like at work. I could’ve asked better.

And then I had asked under what circumstances would she understand a gender-based choice, for example, if she wasn’t considered for a sales position in a space where customers are used to an old boys’ network of salesmen.

My question in the absence of an HoV may have put her in a tricky situation. Where does ‘inclusion’ figure on the list compared to ‘customer focus’?

As a leader/manager, just talking about values isn’t enough. Rank them, put them in an order, signal to all what choices to make in times of conflict.

Because in the real world values come into conflict.

The certainty effect - a lesson from Better Call Saul

A friend hands you a lottery ticket. The draw is for the next day. Without a ticket, winning the lottery was an impossible outcome; now the hope is real, however small the chances.

Now imagine you’re certain to win a million dollars, except a 1% chance you may not. The verdict is tomorrow. The anxiety is killing you. Your lawyer suggests a settlement that guarantees you 90% of the maximum settlement. You aren’t willing to risk getting nothing at all, even if it’s a tiny one. You settle.

What does this mean?

We get disproportionately swayed when an outcome changes from a state of impossibility to possibility (possibility effect) and from a state of possibility to certainty (certainty effect).

We feel much more optimistic about long shots and we feel much less optimistic about almost-certain outcomes than simple math suggests.

Landing of the first man on moon in 1969 brought about a souped-up wave of optimism around space travel and colonization.

A vaccine with a 95% efficacy is good but doesn’t guarantee peace of mind. A shot with 100% efficacy – who wouldn’t be willing to pay 10X for that?

In the show Better Call Saul, the FBI and DEA want to put Saul away for good for a list of drug-related crimes that’s longer than your monthly grocery list. Saul has no alibi other than a cooked-up story.

It is logical that the prosecution pushes for the maximum sentence. It is also logical that they laugh at the idea of settling by plea bargain with Saul.

Yet when we’ve something we think we deserve to win (a flaky lawsuit or a medical procedure), we’re willing to pay a big premium to eliminate a small risk. The prosecution wants absolute certainty that the case against Saul doesn’t fall through and he gets off scot-free.

And when we have little to lose (a solid case against us or a lottery ticket), we’re willing to gamble for a large gain. Saul’s staring down the barrel, so he’s willing to take his chances in a trial where he has to sow just enough doubt in the mind of one juror from among twelve.

The world we keep searching for is logical. The world that keeps showing up is predictably irrational. Hope and fear carry a transformative power. When an outcome changes from being impossible to possible, or from merely possible to certain, something changes within us too. We think too much or too little of what we have.

In the end, Saul gets the prosecution to settle by plea bargain. They agree to seven years. Seven certain years in prison instead of a possible maximum of a life sentence plus 190 years.

That’s the difference between possibility and certainty.

Do you read the signs?

Pattern matching is a high-leverage skill. You see something and connect it to something you already know. Often the thing you see and the thing you know may seem completely different on the surface, but underneath there’s a thread that only you’ve spotted.

The thing with pattern matching is that you can be great shakes at it for others and yet suck at using it on yourself.

When it comes to your own self, slow pattern matching is the cause of many a late epiphany.

When I was in my final undergrad year, my friends organized an intervention. They took me to task for being a prick. All through high school and junior college, I had been the funny and sarcastic one. Now all of a sudden, my friends, gathered round me, were telling me I was not. I lacked empathy.

Your longest relationship has lasted months, not years? You’re convinced that something was missing in the other person each time.

You end up saying yes when you want to say no? You’ve rationalized your choices by telling yourself that you were doing so to see someone you like happy.

Your last three teams have been unhappy? Of course, you had the wrong people.

And then one day, the inner dialog changes: ‘Could this be me after all? This has happened enough times with me at the center of it, for me to realize that nothing’s missing in the other person, nothing’s wrong with my friends or colleagues, and there’s nothing I can blame the world for. It’s just me’.

I was lucky with my friends. If you’re lucky like me, someone will drop the penny on you. But more often, as the years add on, people will be more nice than kind.

Few will tell you to your face what’s clear as day. Even when you may ask for the truth, those around you will show mercy.

It will be left to you to spot the wrinkle within.

Tiny Thought #10

Thank you for reading! I would love to how I can make this newsletter more useful for you. Let me know in the comments or write to me at satyajit.07@gmail.com. Until next week…