Hi friends! 👋👋

Welcome to Issue #44 of Curiosity > Certainty!

Do you think wool merchants and bankers make for good patrons of art? Well, I don’t think they do normally unless you’re talking about the Medici family during the Renaissance. Lorenzo de’ Medici was an enthusiastic chap. His support to da Vinci and Michelangelo and several others in their era meant we know of these artists and inventors today, more than half a millennium later.

Following the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution, humans came to master mass production. No longer did inventions stay scarce for want of suitable replication technologies (the printing press, for example). But the inventor still needed to draw a crowd. Enter the editor, the publisher, the intermediary, the gatekeeper. Their role was to put forward figures up on a pedestal that the audience should pay attention to. This model continued (and continues) for centuries until digital technology began breaking it apart piece by piece.

The modern makeover of patronage is digital. It may come in unassuming garb but it is hard to miss. Patronage platforms like Kickstarter and Patreon allow creators to raise capital and support for projects, one-time or running, and their audience to cherish the feeling of having chipped in for a cause they believe in. Substack matches a desire on the reader’s side to learn about something(s) they’re invested in with the creator’s want to develop intimacy with her audience. Without anyone in the middle.

I’m aware that moving ahead my writing on decision-making and critical thinking will be no more than a hobby without your patronage. And I’m thankful for the opportunity. I’m also keen to make the most of it and serve you in the best way I can. So, thanks again for being a part of my journey until now. You can and should expect a lot more from what is to come.

Right then, on to this week! I wrap-up on the two-part series on time-travel approaches in decision-making. Last week, I wrote about backcasting and mental contrasting. This week I cover premortems, second-order thinking, and regret.

Premortems - why you should kill your dream project to save it

We agree that talking about failure is healthy, but we forget to think about failing ahead of time.

There aren’t many organizations where people are encouraged to entertain the thought of crashing and burning. Project leaders do not close out meetings with “Folks, we came up with nine reasons our new service launch may fail. Superb job, all!”

But what if they did? Welcome to the land of premortems!

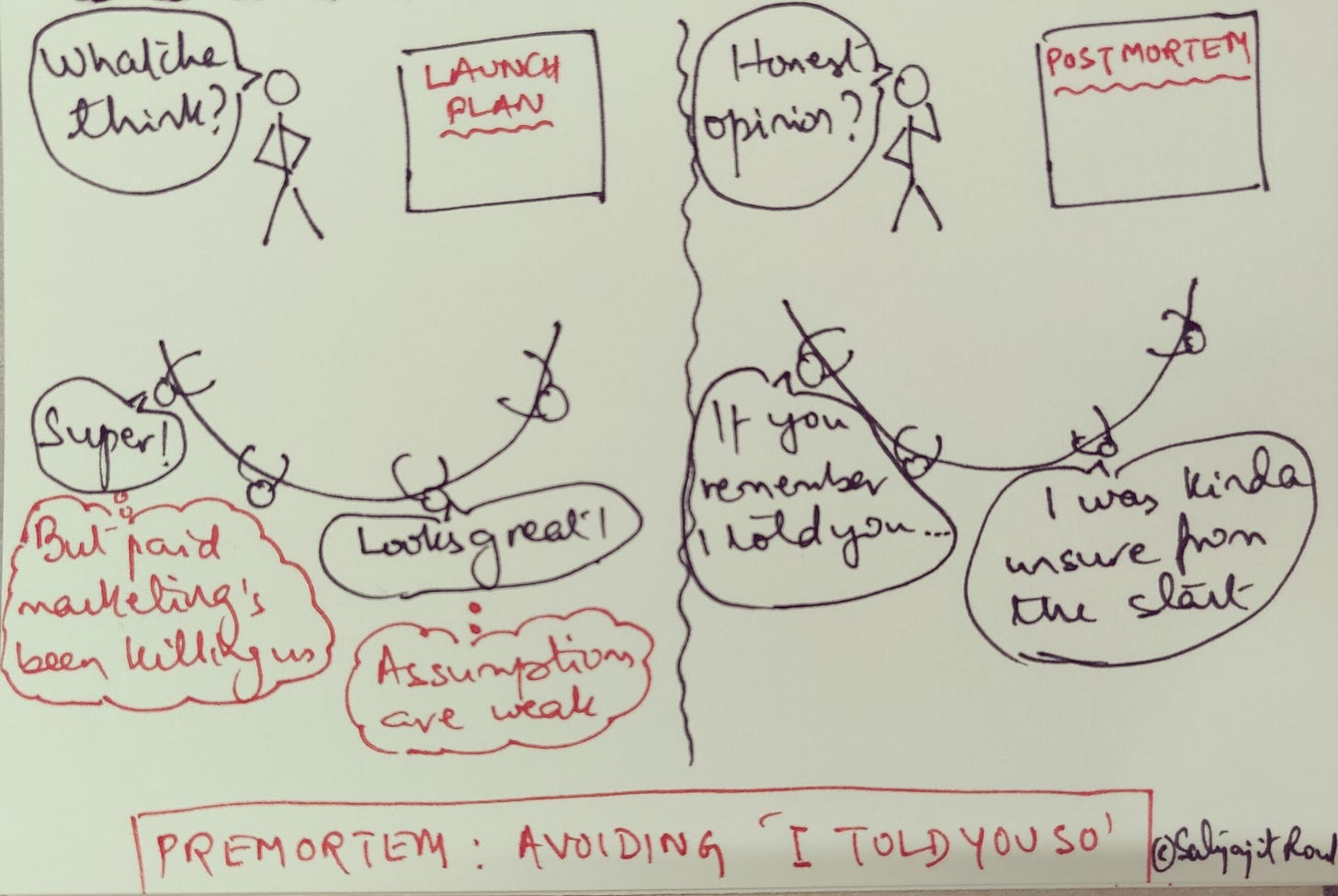

Premortems invert the idea of a postmortem by discussing the cause of death while there’s life. You may know something called After Action Reviews done at the end of the project. Think of premortems as Before Action Reviews done at the start. Why would you do this?

To avoid postmortems. When reviewing failed projects, we slip into what I think of as retrospective certainty: “I knew there was something wrong” or “If you remember, I had brought up the point of…” We’re all hurting inside and we crave feel-good. The goal is to avoid death, not pinpoint the cause of it. So how about nudging your team to voice doubts while there’s a chance to survive?

Gary Klein, the inventor of the premortem, has a simple four-step process for it.

1️⃣ Project leader informs the team that the project has failed spectacularly (“patient has died”).

2️⃣ Everyone separately and simultaneously writes down why they thought the project failed (“probable causes of death”).

3️⃣ The leader then asks each member to read one reason from their list and curates all reasons voiced.

4️⃣ After the meeting, the leader reviews the list and strengthens the project plan to counter all problems.

Tips to help you replicate a pre-mortem at your workplace:

✔Role: Project leader is NOT the project manager. You need someone with clarity and oversight.

✔Timing: Do a premortem before project execution, not before project planning. You want to have a plan to find holes in. At the same time, it should not be so close to launch that it doesn’t allow you time to pre-correct. Think clearly about what the best time frame may be like for you.

✔Habit: Shreyas Doshi, a big proponent of premortems as a way preventing problems, understands what helps his teams easily recall problems for later action. So he asks people to tag problems of different sizes ('tigers, paper tigers, and elephants')

Organizational optimism is useful. It is what drives people along in the face of uncertainty and pushes them forward in the face of setbacks. But it also harms if not paired with negative visualization.

This is where premortems beat postmortems!

Second-order thinking for organizational decision-making

When we think of a decision we look at the effect it may have. And then we stop. But the effect has an effect too. Second-order thinking is thinking about the effect of the effect. The need for it becomes clear when you look at how organizations design incentives.

👉First-order thinking (FOT): Procurement setting up 40-page requests for proposals (RFPs) that takes bidders months to meet, and then offering only a snappy decision email to those who miss out

👉FOT: Running an org-wide initiative to come up with a set of values that define the cultural operating system of your organization (example: fail fast and break things)

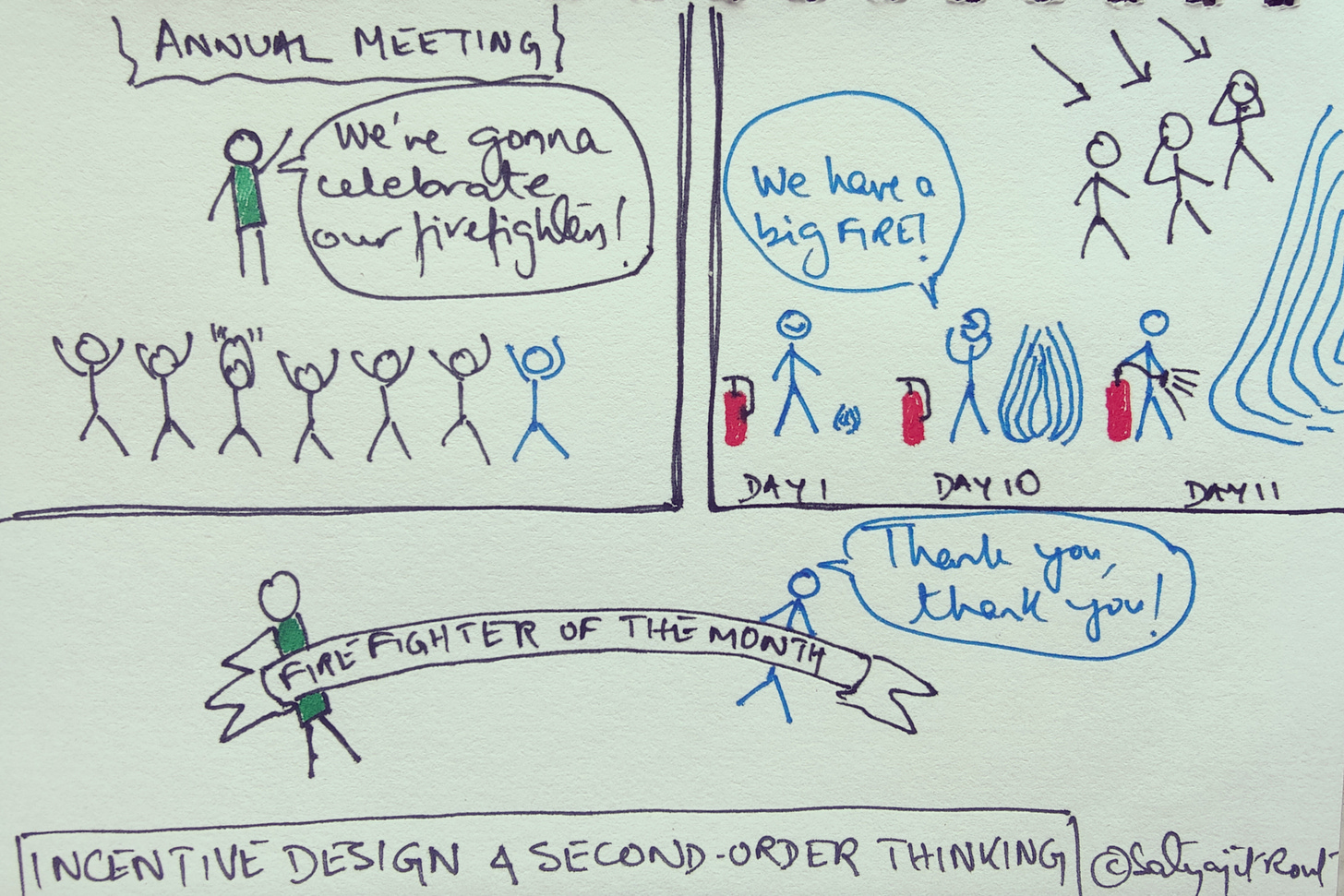

👉FOT: Recognizing the efforts of employees who fight fires and solve business emergencies

Each of these first-order decisions makes sense. You’re trying to do something right.

Except that when you pause to consider the subsequent effect of these decisions, you may see a different picture. The best vendors start ignoring your RFPs. Your culture isn’t what you imagined it to be. There seem to be a lot of fires around that make execution difficult.

Pairing up first-order thinking with second-order thinking teases out the ripple effect of your decisions. 𝐘𝐨𝐮 𝐝𝐨 𝐬𝐨 𝐛𝐲 𝐚𝐬𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 ‘𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭?’ 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐝𝐞𝐜𝐢𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐲𝐨𝐮’𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠. 𝐃𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐬𝐨 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐲𝐨𝐮 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭 𝐛𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐮𝐟𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐲𝐨𝐮’𝐥𝐥 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐛𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫.

🔑Second-order thinking (SOT): Losing bidders in an opaque RFP often feel disgruntled. So shorter RFPs with transparent decision criteria and assured feedback to bidders for the pain of applying.

🔑SOT: Having a set of values to guide behavior is necessary. But it may not be sufficient if applying them is left to employees' discretion. Operationalizing values by clear process is a better guarantee of desired culture (example: If your value is ‘fail fast and break things’, reserve a few minutes in every team review to talk about what you broke & what you learned).

🔑SOT: Employees who take charge in a difficult situation are worth their weight in gold. But an unintended consequence of feting fire fighters is that employees may be incentivized to light fires to fight fires. What you want is to prevent fires. What are the incentives you have for fire prevention? What can you do to encourage employees to raise red flags without fear? And what system do you have to receive these signals?

We live in the land of the seen. But what affects our future is often unseen. Ensuring we think of both the seen (first-order) and the unseen (second-order) is what gives us the best chance to execute our plans.

If you like this post, or my writing in general, why not refer a friend who may enjoy it the same as you?

‘Love, can I have my regret before I take action?’

What is common to the phrases buyer’s remorse, a heavy heart, and crying over spilled milk?

They are all expressions of regret. Regret as we recognize it happens after the act. A chain of events have been set in motion and now we have no control over them. It also tends to be all-consuming as we’re not the best judge after a poor decision. What if we could move regret to before? Before the lapse in judgment, that hot emotional moment, that chain of events.

Here’s a simple protocol to practise.

Set a tripwire: This is to recognize the trigger. A sharp email that just arrived, a loss limit on a stock, or a losing streak in a game of poker. There are more situations when one’s impulsive than can be listed out. So a better indicator would be to clue in to how you feel emotionally and physically. Look out for sick, angry, rushed.

Take a timeout: This break wasn’t there before; it has been introduced by you. That intentionality is important for you to own the moment.

Time-travel: This is the main part where you take help from past-you and future-you to make a decision that the present-you is likely to be rash about. You can evaluate your options using Suzy Welch’s 10/10/10 system. Ask:

‘What are the consequences of each of my options in 10 minutes? In 10 months? In 10 years?’

You can go with the bigness of the decision to decide the time frame. It could even be 10 minutes, 10 hours, and 10 days if you’re about to give in to the temptation of cheating on your diet.

If you don’t get a clear answer from the future-you, Annie Duke suggests a great addition to the practice. Talk to your past-you. You have a rich set of experiences to learn from. Ask: ‘How would I feel now if I had made this decision 10 minutes ago? 10 months ago? 10 years ago?’

Anticipating regret before it has happened may sound novel but is not. It’s how we stop ourselves from killing the next person who cuts us on the road. We do it every day, just not intentionally or often enough to acknowledge it. Making a habit out of imagining regret can save us from going on guilt trips later.

So why not just count to 100, you may ask? Why all these protocols? What you want is something immersive and something you can take a lesson away from. That is best achieved with active reflection. Placing regret before your decision is forcing yourself to reflect on the consequences of your actions ahead of time.

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading! read

Let me know what you made of my thoughts on modern patronage and this issue. I would be delighted to hear from you. Spread some ❤ by sharing it with a friend or two.

Until next week…