#4 - I've had the most fun when I've let myself be excellent at being mediocre

Mediocrity is excellence minus social signaling

I had this issue with the question of when to turn in a project. It veered to the obsessive, while rewriting my first manuscript in 2012. I did at least six full edits of a hundred-thousand-word manuscript with the goal of getting an agent to represent me. I didn’t enjoy that phase and you would think I would’ve cut my losses and moved on to better things. I did but I discovered my natural strengths in a roundabout way. This discovery, still unfolding, has been more than a decade coming.

Cut to present time. I've adopted the precisely opposite approach in the last six longform writing projects I've worked on. I’ve started each of these pieces with a clear goal—one or a couple of particularities that I care about in every piece. That’s what I've set as the goal. How close to what I set out to do with this variable is what I measure myself by. I'm clear about the point when working further on the piece will only bring marginal returns and I'm much better off starting something new. So after I finish my draft, circulate it for feedback, incorporate the feedback, I hit publish, and I move on to the next project. No dragging my feet.

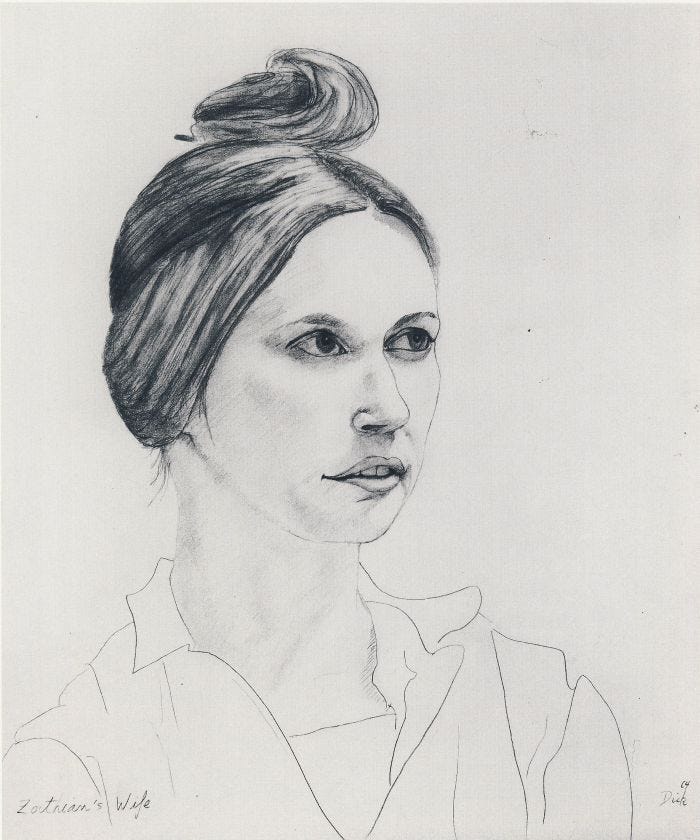

With my most recent piece, a fictionalized true-crime novella, I spent fifty-seven days working on the first draft. And fifty-four of those days I felt like shit. I know this because I only felt like the story was coming together in the last three days. The feeling was so rare it was memorable. I couldn’t explain to my wife my jaunty manner.

In this story, I wanted to focus on dialog writing. So, I started reading Cormac McCarthy who probably wrote dialog as well as anybody ever did. This was a very high bar. I shot for the stars and (invariably) failed. Which meant my performance was mediocre. This is a longstanding pattern that I only just spotted.

As Venkatesh Rao says, you’re deliberately solving for the passing grade rather than the perfect score. You take care of those details that matter for survival. The rest you leave hanging because the returns for tying them are diminishing. Not a perfectionist. A mediocrat, perhaps.

Rao reframes perfectionist as a completist (cares about the complete set of parameters), as a nihilist (hence cares about nothing because she doesn't make trade-offs), as a maximalist (sets the performance parameter to maximum by default)

I’m not a perfectionist on any of these counts when it comes to my recent writing. Upon a little reflection, I figured it’s the same when it came to paid work as well, back when I had a job. Over the last decade and a half, I’ve built a body of work as a generalist moving across corporate strategy, business development, sales, operations, and the works. Find and invest in early-stage startups, scan the market for new opportunities, incubate a new business line, build teams—this is the work I’ve enjoyed the most. Work where I was learning and in all possibility I was mediocre (which others were scared to take up, I suppose).

What’s the point in being mediocre? Earlier I mentioned that I set for myself a high bar in my writing efforts. So much so that even falling (well) short was an improvement upon my baseline level of skill. This way I’ve tried my hand at structure (John McPhee), dialog (Cormac McCarthy), non-chronological character sketch (Mark Singer).

Perhaps being consistently mediocre would have been a problem had I been writing to plan. But I wasn’t, thankfully. I was writing to learn. To just get better at something new. I realize now that my natural affinity toward optimizing for learning (and the resulting mediocrity in performance) is not that unusual.

Running is a good petri dish for examining mediocrity. For a period of eight years, I ran long distances. Half and full marathons. With time, my experience didn’t get easier. If I started with laboring to complete a half marathon in under two hours, after a few tries I struggled to finish it in an hour and three-quarters. This optimization continued until I switched to full marathons. I became slower again and then gradually bettered my own times. Running never got easy for me. I was consistently mediocre at what I was trying to do.

When we finish a grade in school, we don’t attempt it again with the aim of doing it better, that is, optimizing performance. We don’t repeat even when we finish in the middle of the pack. We wrap up the learning stage and move on to the next one.

For a while I have been marinating in my head a character sketch of my masseur, an old-school archetype who comes home and chats with you while he’s kneading your body to pulp. I’ve done three character sketches in the last eight months and if I were to take a stab at this one, I suppose I’ll shave off at least a fourth of my median time. So say 75 hours, give or take. That is typical optimization. But instead, say, I decide to level up the challenge and go ahead and piece this sketch together by interviewing only his clients (something I haven’t done before). My masseur is networked, so he has probably a hundred clients I could speak with. Speaking to them would help me get a 360-degree perspective of my subject. It would also mean I'm back to my median time, or even further back. Because I would be operating at a new level. I'm learning the ropes of a new skill—interviewing strangers. That will set me back. I'll be mediocre at it, at first. Instead of being excellent at a pre-existing level, I’m now being mediocre (sucking, essentially) at a higher level. That is how learning happens. The improvement, as Venkat Rao points out, is not quantitative (shaving off time) but qualitative (doing something new).

This approach to writing, though new, feels more natural to me than my previous one, which I employed in the previous avatar of this newsletter from, say, 2022 to 2024. I exhibited a kind of continual optimization behavior. Where the goal was to produce a great weekly article, akin to flexing a well-toned muscle, instead of building a new one. I was writing the same article fifty times, trying to make it slightly better with each rep. Without being able to name it, I was unhappy operating this way.

For much of last year, writing this newsletter, I believed I was pursuing excellence. That doing a thing well mattered to me, and hence polishing a piece from an 80% grade to a 90% grade meant something to me. It did; it does. But I like picking up new skills, working on new dimensions, even better. Excellence may be important to me but not over learning. Which means, I’m okay being mediocre for much of the time.

If I didn’t enjoy it, why did I stick with it for so long? My behavior was especially puzzling if you consider that I wasn’t obligated to produce this stuff I didn’t enjoy producing. No one asked me to. This is where a social performative aspect comes into play, I believe. I was conscious about the stuff I was putting up and I was caught up in the loop of trying to appear good, if not excellent. Weekly optimization may have improved my ability to write one type of article, nudging the level of the output up turn by turn, which is what I thought was worth doing. This whole thing was really a glorified exercise for gritting my teeth through diminishing returns in order to claim the boast of some local maxima—social plaudits in the form of shares and subscribers. This was writing to an externalized plan. It didn’t feel good.

This is a good point to talk about a couple of closely related topics:

(1) slack, or fat as Venkatesh Rao calls it. What I have not experienced is doing something well enough with spare change. High-fat, high-excellence is operating at a high level while having slack in the performance. It is Roger Federer winning on a bad day, Lionel Messi scoring a hat-trick without putting on his afterburners. An imperfect performance by their standards, but still brilliant enough for the rest. I believe high-fat high-excellence is the realm of the masters. It is the definition of mastery. I’m far from that territory.

(2) finite and infinite games. Writing to plan is a finite game. You execute as per what you have set out to. Writing to learn (or even writing to write) is an infinite game. The point of the game is to keep playing. Keep learning, keep exploring new dimensions. That’s more my jam.

These topics deserve lists of their own, so I’ll put a pin on them for now.

Looking at how I operate and my body of work at my job and in my writing, I’m leaning toward the belief that I’m not excellent. I’m excellent at being mediocre. It comes naturally to me. That’s my default setting. When I have been able to check my ego out at the door, doing new things continuously has been my path of least resistance. (When the ego comes in, I start optimizing for social acceptance and I dislike the experience).

The mediocrity that I show time and again is to me a form of excellence in itself. It is excellence minus social signaling. This is no garden-variety socially acceptable excellence. But it is worth protecting. I want to keep sucking at something new without caring much about what others think. The better I get at not caring, the easier it will be for me to learn. The better I can do my thing without worrying about how the thing will turn out, the more fun the act of doing will be.

As Venkatesh Rao says, you’re deliberately solving for the passing grade rather than the perfect score. You take care of those details that matter for survival. The rest you leave hanging because the returns for tying them are diminishing. Not a perfectionist. A mediocrat, perhaps.

This is something I am going to revisit time and again. Thanks for surfacing it Rout!