#39 - Hooking up with the right crew AND asking your way out of trouble

The power of company in habit-building and the power of better questions in decision-making

Hi there! 🙌

Welcome to Issue #39 of Curiosity > Certainty!

As a creator, one of the classic dilemmas is: create for yourself or for your audience. Podcaster, writer, and sneaky artist Nishant Jain–also a friend and mentor to me–who does the wonderful SneakyArt Post and SneakyArt Podcast speaks lucidly on the subject in the latest episode of his podcast.

Last year, when I started this newsletter, I used to do longish-form essays. I liked the process of starting with the nub of an idea and then letting my associative mind lead me. Two pieces that capture this style would be this and this.

Now I write in a shorter format, in a way that I hope is easier for the reader to distil actionable advice. It is something I’ve grown to like and enjoy doing. How do you find it? It would mean a lot if you let me know.

In this week’s issue, I explore two ideas. Idea #1 is how do groups and communities affect habit formation and can we build better habits by hanging with the right crew. Keen readers will point out that I didn’t do the pop neuroscience angle as promised last week, but that’s on the way. I will do better than to promise again. 🤦♂️

Idea #2 deals with a grossly under-rated decision-making skill: asking good questions. If I had to get better at decision-making and I had only 24 hours to do so in, I would spend most, if not all, of that time learning how to ask better questions. It is an uncommon skill that unlocks value. 🔑

Ok then, on to this week’s edition!

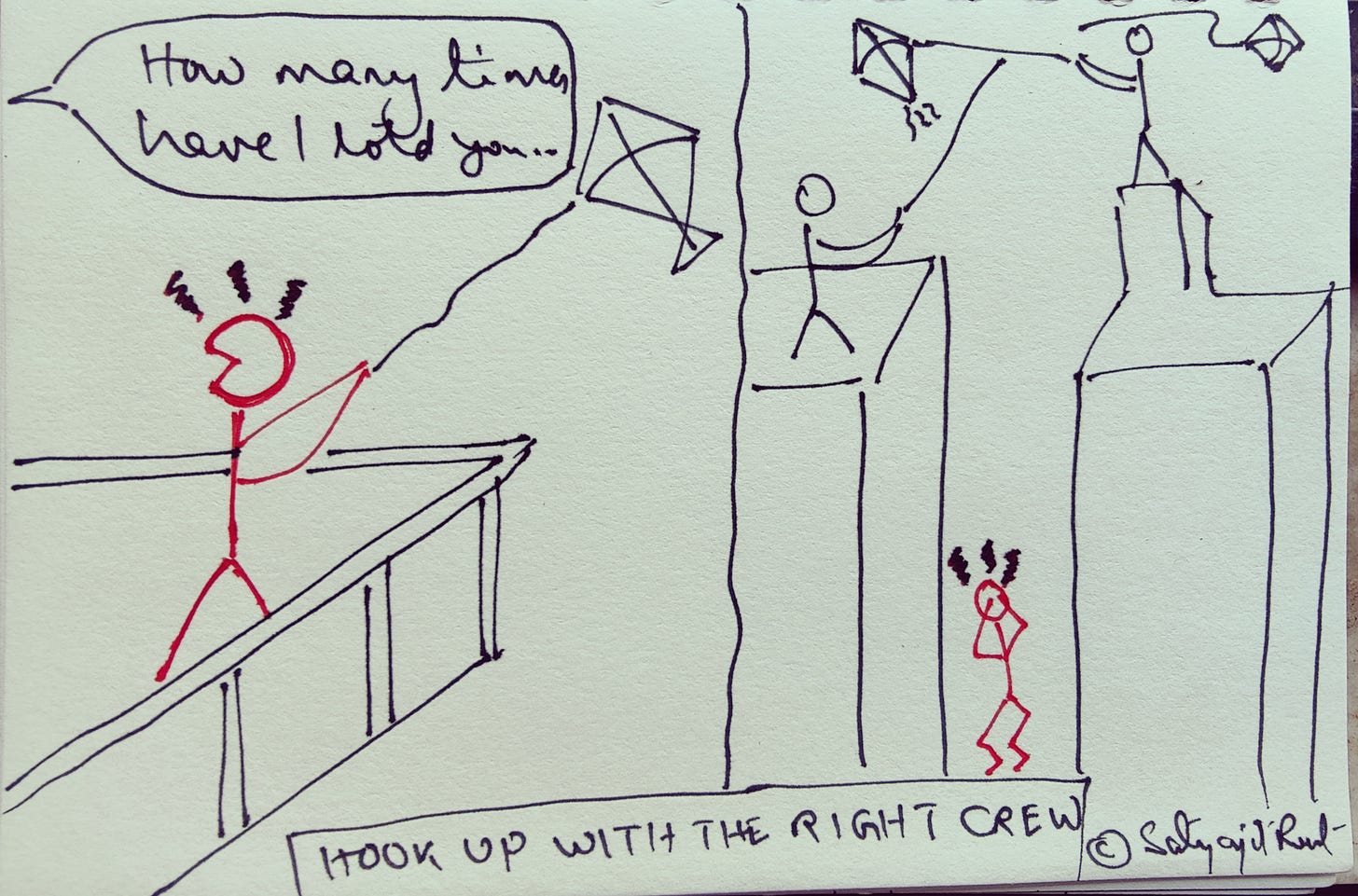

Building habits by hooking up with a crew

My mother believed kite flying to be a dangerous sport. She would go back years to recount all neighborhood accidents when kids, chasing kites, had fallen off rooftops. She also made this clear to my friends. I was thus forced to fly kites by myself on the sly. For those unfamiliar, kite flying needs prep (coating thread with powdered glass) and shared knowledge to succeed (kite-cutting, reeling in).

All alone, I sucked at kite-flying and the experience was more frustrating than fun. My mother won, for good.

Identifying closely with who you want to be is a powerful driver for habit change. Your personal identity pushes you to cultivate desired routines. But the process of carving out your own identity gets expedited if you swim with the current. The current is nothing but your group identity–the tribe you belong to.

Our earliest identities are not those we choose. They are what we see around us. We mimic nonconsciously what we see people around us do.

As social animals, we have an evolutionary need to blend in. Anything that makes us stick out from the pack is something we’re more likely to give up. Tribe identity overpowers personal identity. You can make that work for you as a feature, instead of trying to debug it.

If you want to build a habit, join a group where that is routine. If you want to quit alcohol, join AA. If you want to read, join a book club. When personal identity is aligned with tribe identity, it creates a powerful tailwind.

How does it work? When you’re part of a tribe you identify with, a shared craving is at work. The desire for a specific behavior is not just yours but of everyone around as well. The appeal of a routine is multiplied when you see many others around you engaging in it. You improve by learning from other’s mistakes too.

This can work against us as well if we are drawn to the wrong company. The pressure to comply then forces us to engage in unproductive behaviors, and soon we’re in a downward spiral.

We often take pride in being the lone wolf. The lone wolf dies early (like the kite-flying me did) or at least takes longer to learn. Instead of fighting our desire to fit in, we can harness it by hooking up with the right crew.

Habits at scale is culture. Are you part of the right culture?

Imagine yourself, young and nervous. You’ve gathered the courage to sidle up to your mother and tell her that you’ve decided to drop out of college to start a T-shirt company. As you try and stitch the words right, your grandmother walks in and chimes “Like mother, like daughter.” Newsflash: Your mother had dropped out of school to start something on her own. Suddenly, a weight is off you.

We’re born imitators and there’s no better model worth emulating than what we’re born into. Our families are the first social group we seek permission from; seeing someone from the family pursue something empowers us to do the same.

The same craving for social conformity forces us to study harder in a high-performing peer group or follow the same career as our friends.

The model of “copy and paste” as Katy Milkman, the author of How to Change, calls it is everywhere and at scale too.

When group behaviors flourish they lead to social norms. Mumbai is a commune for entertainers, Montreal to clothing businesses, SF to tech companies, and so on. Those in these bubbles don’t see anything special. Those outside are left to wonder: “What’s up in the water there?”

You may wonder what it has got to do with your own quest for habit change. Consider this: You’re an adult and you believe you can think for yourself. Yet, study after study shows that the idea of freethinking man is a myth. We’re highly vulnerable to what Robert Caldini calls peer-suasion. You can call it peer influence.

This much has always been true. What has changed is that the levers of social influence have been turned up several notches. While in the pre-Internet world you paid an admission fee to join a group, the barrier to participation today is next to nothing. While it took years for a physical cult to set itself up, digital crews today pursue a quicker path to followers.

This urgency brings both freedom and caution.

Because it’s not just businesses and creators who are using the power of social influence to create minimum viable communities to further niche causes, it’s also the alt-rights and the QAnons who are betting on our tendency to be social sponges to trigger our collective madness.

What you copy and paste into your life needs your attention. You want to use the wisdom of the crowd to reach your goals, not be sucked into poor choices by the madness of the crowd.

Decision-making with less: the seed of creativity is in constraint

What does decision-making without constraints look like? Here are three high-stakes examples.

👉René Redzepi, head chef of three Michelin-star restaurant Noma, only uses native Nordic ingredients to create delicious food. Nordic winters are long and unforgiving. Foraging for ingredients is tough. But being forced to do so is a recipe for surprise: “plucking grass from rotten seaweed to find it tastes like coriander or biting into ants to find they taste just like lemons.”

👉Writer Neil Gaiman always writes his first drafts on paper. When he was editing a short-story anthology in the late eighties, the average entry he received was about 3000 words. Five-seven years later, that swelled to up to 9000 words but these entries “didn’t really have much more story than the 3000-word ones.” Wondering why, he realized it was the ease of word processors over typewriters and handwriting. Adding words wasn’t work, choosing was. The computer led to turgid writing. The typewriter or the fountain pen made you write careful prose. That’s what is most important to a writer.

👉Retired US Army General Stanley McChrystal believes military leaders are better at developing leaders because they don’t have the luxury of throwing money at the problem. They do so by maximizing purpose for soldiers because they cannot distribute bigger annual bonuses to employees, like civilian leaders do.

You will not find a decision-maker without constraints. Some will even welcome them. Why? Because the best decision-makers can take a limitation and create a better solution out of it.

This is how they think.

Constraints remove distraction. Direction emerges when distraction goes away. If progress is speed in the right direction, having direction means progress pared to a single dimension. Scalar is much easier to tame than vector is. Now you have your path set out. Now you are free to gather speed. Now you are free to create.

Before you plunge into your next decision worried about the things you don’t have, ask yourself: What if there’s nothing to change about your situation? What if this is it?

And then just leave your mind wide open.

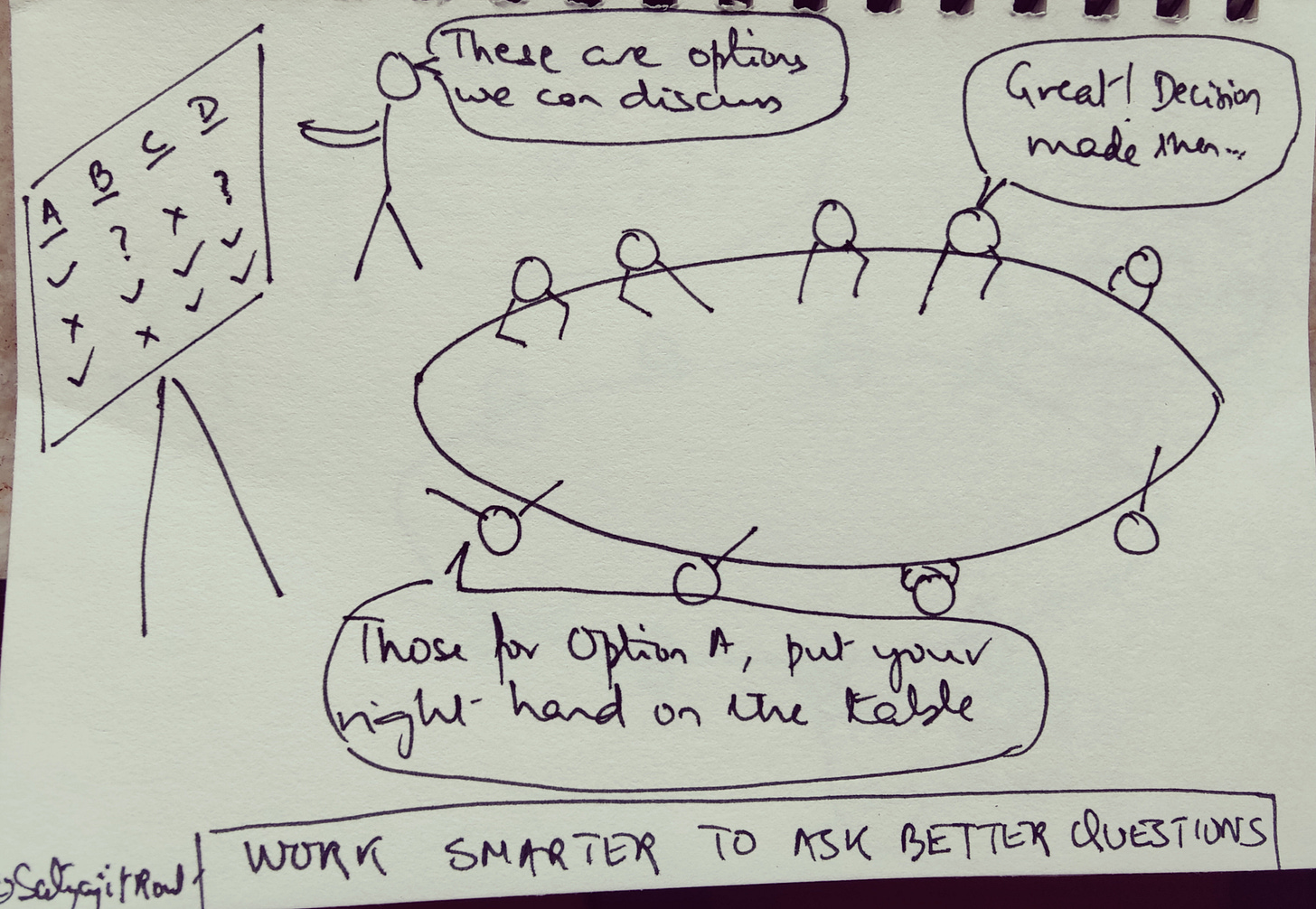

Better decision-making by asking better questions

This is what Shopify CEO Tobi Lutke has to say: “Your skill in decision-making is directly proportional to your quality of information acquisition.”

Your decision quality cannot beat your information quality. Quality information is hard to get. You can’t always be running experiments. You gotta ask good questions. But not many recognize its worth. A high question-quotient is uncommon, if not rare.

Take these common scenarios.

#1: You’re in a position to influence but you don’t have authority

You’re in a meeting with heads of business units exploring a diversification strategy. Everyone is more experienced than you. It has taken weeks to set this one up, but now the discussion seems to be converging a little too quickly, or it isn’t going anywhere. You want to challenge the group’s assumptions. But you’re in a room of people who seem to know what they’re doing. So you clam up.

#2: You’re in a position of authority but you don’t want to influence

You’re the boss. You want unfiltered information to make up your mind on a critical business decision. You quickly and clearly set the context for the core group and ask them leading questions: Should we go ahead or not? Do you think you’ll be able to give this bandwidth? Soon enough, you have the answers and you go with them.

#3: You’re consulting a specialist industry expert about a new market space

You’re paying by the hour for this expert. You’re hoping you’ll come out with clear direction from the consultation. So you ask predictive questions that leave little room for ambiguity: Do you think we can win in this space? Is this a market trend that’s going to last? The hour’s done and you think you’ve got your money’s worth.

Whether you zipped up or leaned in or asked an expert to crystal-gaze, you probably could’ve gotten more out by asking better questions.

Here’s one thing you could’ve asked in each of the scenarios to unlock the right information:

✔#1 “What would have to be true for each option to be the right one?”

✔#2 “Imagine a future where we’ve made this decision and it has backfired. Write down what you think went wrong.”

✔#3 “What should I be looking for in a case like this?”

What’s your favorite question to ask to unlock insight?

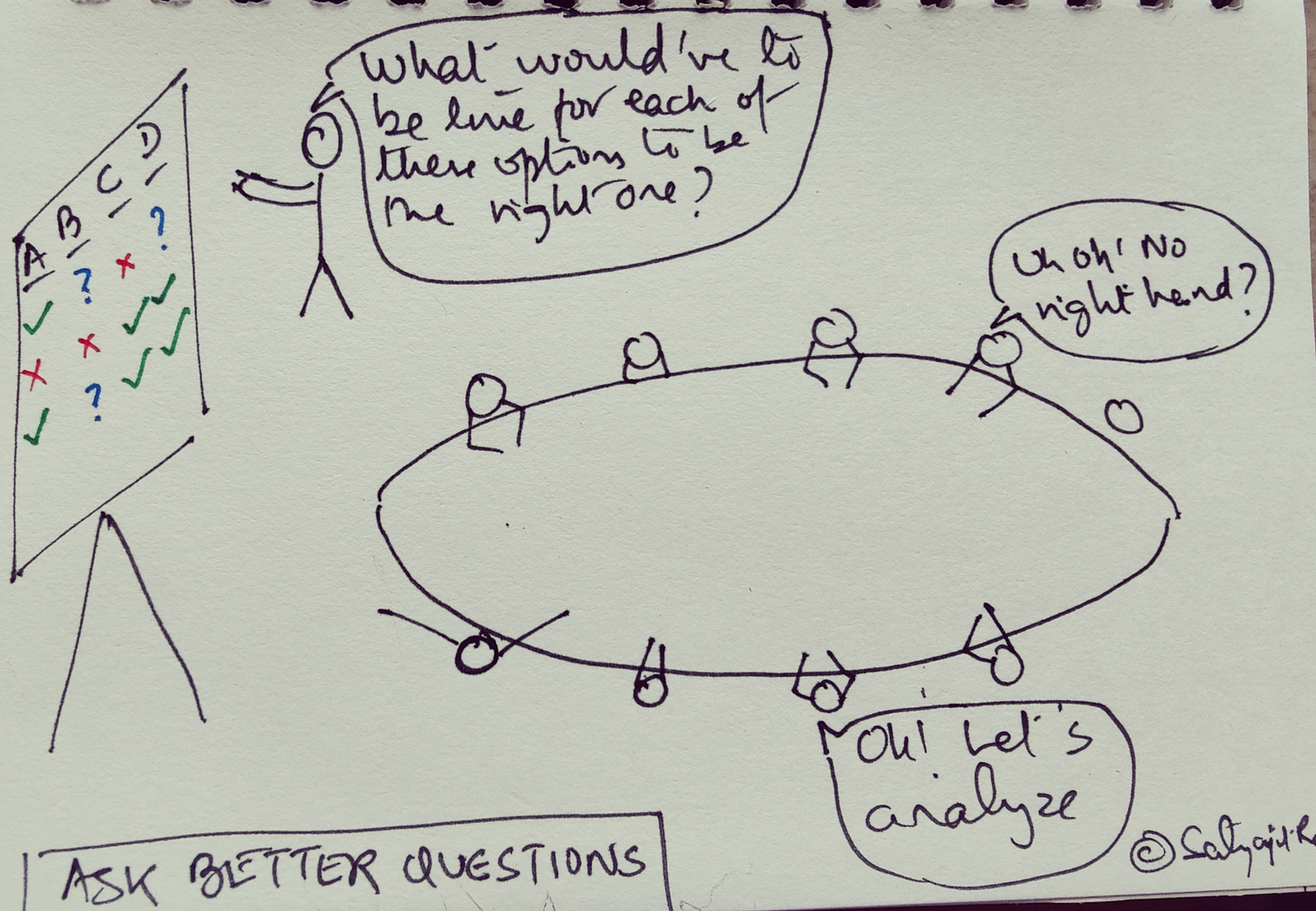

How to run strategy meetings without authority (aka how to spark disconfirming analysis leading to better decisions)

When you’re running any consequential discussion among business leaders, as a young professional you may find yourself in one of two situations: the discussion converges too quickly OR it moves around in circles. The best way for you to drive the discussion is to steer it in the right direction. And that direction is away from preconceived position-taking AND toward open exploration.

The goal of asking good questions should not be to appear intelligent or to make sure answers aren’t vague. The goal is to study both the seen and the unseen.

If you’re in a position to influence but you don’t have authority, you want to turn the collective attention to the unseen.

I used to kick things off by setting the table and sharing the dinner menu with all guests until I realized my guests will just have what they want to have in the order they prefer. It is natural to become frustrated or judgmental in such a moment. If you’re like me, a small change can help you.

The desire for group harmony often shows itself in narrow problem framing (‘X is the only viable option so the question really is should we do X or not’). On the other hand, endless debate often springs from not knowing (or not agreeing on) the most important thing, so you have people, like at a party, arguing about completely different things without realizing so.

Roger Martin, author of The Opposable Mind, suggests issuing the decision-making group a simple challenge without challenging their world view. This is how you could frame it.

“Let’s stop for a moment debating which option is best or which view is right. Let’s take each option on the table and ask: What would have to be true for this option to be the right answer? What is the evidence that would convince us about an option?”

The question works in two ways: it draws attention away from the beliefs of the answerer and it triggers a search for conditions in which an option is the best one.

A belief-based discussion is seldom productive. An evidence-focused exploration is almost always is. The way to make that switch is through a simple reframing.

So the next time you want to spark disconfirming views without appearing contrarian, ask out loud ‘What would have to be true for this to be right?’

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading!

Let me know what you made of the issue. I would be delighted to hear from you. Spread some ❤ by sharing it with a friend or two.

PS: Something nice and unexpected happened this week.