2X2 Decision Matrix & Cognitive Dissonance

How to decide well and how to not remain at odds with oneself

Part I: How to decide well

I went from being stressed by too many daily decisions to having time for the truly important and big decisions with a simple change. You can learn the basics in two minutes. And like any good system it works everywhere–work and life.

We often spend too much time on the small decisions and not enough on the big ones. Some of it is fear. We don’t want to tackle the big bad problem just yet. Most of it is a lack of differentiation–we treat all decisions the same.

No one remembers how well you crafted an internal email to put out a fire, if those fires happen every day. I bet even you don’t recall your best email from yesterday.

Through a simple system of transfer of time from the small to the big decisions, we can create more mental space for the tough decisions. For that we need an easy way to tell big from small.

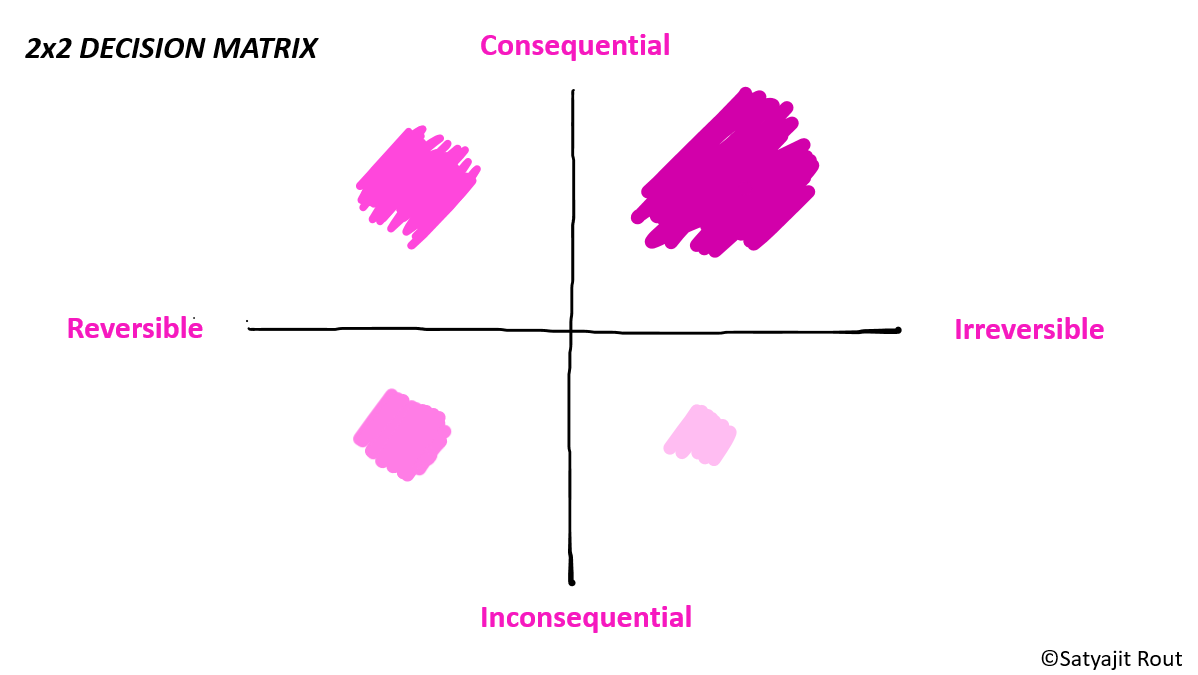

Decisions fall into a simple 2X2 matrix of consequential vs. inconsequential and reversible vs. irreversible. This is something I learned from a decision-making course by Farnam Street.

All the big decisions in our lives–whom we spend our lives with or whether to buy a house–are consequential and irreversible. They deeply affect our future and we can’t go back once we make them. These are the “Lead Domino” decisions. They are connected to everything else–family, freedom, fulfilment.

All other decision quadrants are where we need to spend less and less time. These apply to tasks ranging from those that produce marginal results to those that are downright unproductive. Outsource, delegate, offload. Tip: Get the person most affected by the decision to make it. But also coach them. Remember it’s a big decision for them.

What the 2X2 Decision Matrix does is examine our excuse for busyness by pointing and asking: This is what is most important; are you spending your time here? It forces us to allocate time to our best interests.

So take a piece of paper. List down all the decisions on your mind. Fit them in the decision matrix. Are you spending your time well?

Note: Curation allows me to triangulate and share that which works consistently. The 2X2 Decision Matrix is consistent with Jeff Bezos’ one-way-door and product guru Shreyas Doshi’s leverage-neutral-overhead task frameworks.

Part II: How not to remain at odds with oneself

I noticed in the 80s Bollywood hit My Name is Anthony Gonsalves that girls swooned when Amitabh Bachchan sang ‘Because you are a sophisticated rhetorician intoxicated by the exuberance of your own verbosity’. The words, of course, were a joke but try telling that to a little boy who swore by Mr. Bachchan.

English dailies of the time, too, were full of long sentences and words with more syllables than less. Exposed to all this, my pea brain concluded that the point of writing was to impress. Teachers, if not girls. An essay about the pernicious effects of atmospheric pollution fetched better grades than one about the mere harmful effects of air pollution. The occasional asks by friends to write simply did not dent my confidence. ‘It was a matter of style’, I told myself. ‘I write well’.

Recently I joined a program about the art of clear writing where the first lesson was that writing clearly is writing simply. And that a good writer writes for the reader. Ouch!

Cognitive dissonance happens when we receive information that conflicts with our beliefs. It creates mental discomfort that urges us to reduce or remove the internal inconsistency. Existing belief: My fancy style is what makes me a good writer. New idea: Simple writing is better writing.

Our beliefs shape our world but can be inconsistent with new ideas or with each other. We respond to this gap on a spectrum: from outright rejection to behavioral transformation.

I’m not interested in what the right response is, or if there’s such a thing as one best response for all. But I want to talk about what happens when we discover a breach in our belief system. I felt this immense urge, almost compulsion, to re-discover my equilibrium once I started examining my writing. The more dearly held the belief, I realized, the greater the urge to stay close to base.

This is the nature of the filter through which everything has to pass through before entering our world. It explains how we consume information, how we decide, and how we live.

When you want to become a better version of yourself, oftentimes the first thing you’ll notice is that the process brings you anxiety instead. That is your internal filter being cleaned. Don’t regress. Don’t react to the dissonance. Stay the course. The half life of cognitive dissonance may be short. But the wisdom from a process of self-discovery will last long.