#195 - Designing a dream balcony and a fulfilling career: how they’re surprisingly similar

Design principles to avoid career misfit

We moved into a new apartment a month ago. Through this month, the highlight of our new place has turned out to be, without a shadow of doubt, this nook overhanging from the living room—a space we weren’t sure what to do with when we first moved in. It afforded a nice view and let in a brisk afternoon breeze, but it wasn’t clear if previously it had been anything more than a planter area.

We found a space so tiny that it fell short of the functional standard for a balcony. It was three-feet deep. You couldn’t sit, chat, and certainly not cram a table in. It was useless as a balcony but, for the lack of better architectural chops, I’ll call it that.

Yet, despite its unalterable limitations, this balcony is now the hub of our family life.

At this point, I must tell you what I’m going for with this piece. I’m going to show you a better way to design your career with a recounting of a simple home improvement project that I believe offers rich parallels to your question of how to design a fulfilling career for yourself.

What is good design?

“In designing a house and a garden, what should you think of first: the house or the garden?” asks Ryan Singer of Basecamp and Shape Up fame as he summarizes the work of design theorist Christopher Alexander.

More pertinent to the readers of this newsletter, in crafting a career that is financially rewarding, what should you think of first: the money or the work?

A garden can be functional in far fewer configurations than a house can. A garden depends on the sun, the wind, and the soil to come alive. It has more dependencies. A house can be designed in a hundred different ways as per your requirement.

Likewise, there are a lot more ways to make money than there is work that hits the spot for you. What suits your interests and your temperament is perhaps a tiny sliver of all options. That’s the sweet spot for your career.

But many — most? — of us think of the money first. We may even have a number in mind — make an arbitrary number (the equivalent of million dollars?) before an arbitrary age (thirty?). Such thinking reflects a common design flaw.

In the 1960s, Alexander introduced three elementary concepts of design. These elements are common to every design problem.

Form - the thing we’re going to make (or modify)

Context - the experiences or activities the form will allow people to have or do (that they currently struggle with)

Fit - how well the form matches the context to ease the struggle of users

Some examples to help you warm up to this trifecta:

👉Form - residential building; context - allow people to live well and do the things that enrich their lives; fit - the degree to which the building succeeds in making its residents’ lives fun

👉Form - a smart writing assistant; context - solve users’ specific writing problems; fit - the degree to which the product does that for its users

Now, form need not be limited to a physical object or a piece of software.

👉Form - your career; context - your interests and temperament; fit - how well your career suits you

“The form is the solution to the problem; the context defines the problem,” wrote Christopher Alexander in Notes on the Synthesis of Form.

Designers, including us knowledge workers, tend to obsess about problem-solving and ignore problem-defining. Some ways we see this:

❌A building doesn’t have a courtyard for residents to gather at, so that neighbors end up being strangers.

❌A smart writing assistant doesn’t understand whether you’re writing an application or a limerick, so it makes you sound the same every time.

❌Am ambitious go-getter builds her career on certain arbitrary standards of financial security and prestige, so that her career is insensitive to the kind of work that energizes her.

The forms (building, writing assistant, ambitious career) in these examples don’t speak to the context (meeting people, writing in different styles, having a career that reflects you). Form-context misfit, all.

Singer, who has been a student and practitioner of design for over twenty years, believes Alexander’s design primitives carry value across domains. I’ll use this as a jumping-off point to consider the principles of career design.

Defining your career design problem

A good entry point into the career design problem is to start with what Alexander said: We think too much about form (solving a problem) and too little about context (defining it well).

Some examples of this that you may have heard:

I want to retire at 40 (or I want to become a CEO by 40).

I want to travel the world.

I want to live on a farm.

In these examples, retirement (or CEO-ship) is presented as the answer. Traveling the world is the answer. Farm life is the answer. Answer to what exactly? What is the struggle that we want to escape with these specific choices of forms? What are the enjoyable activities that we might have engaged in but do not or cannot because we don’t have access to the desired form?

In case you were wondering, these are hard questions to answer. They are also unique to every individual. If the context to people’s lives is singular to them, how is it that these form manifestations are so relatable? How is it that totally different people aspire to the same outward form? That’s what Alexander was talking about.

Ryan Singer summarizes two tools Alexander recommends using to find reliable answers to the question of what kind of a career is meaningful to you. It may get a little dense here, so go at your own pace.

- Choose good centers: All form exists as a combination of elements that are in relationships with each other. A building is made of atoms, a painting of pixels, a piece of music of sound waves – how well these building blocks mesh with each other determines how pleasant or not the final form is. The most salient of these are what Alexander calls centers–a refrain in a song; a recurring motif in a book; a courtyard in an apartment complex; the values your business operates by; your eyes, nose, and mouth on your face. Centers link other elements around them and organize the final form.

- Improve form by solving problems step by step in the correct sequence: It is impossible to design the complete structure for any complex system in one go. The right form unfolds step by step or piecewise in response to a growing awareness of the context. During this process, the sequence of problem-solving is important. Designing the garden first leaves you with plenty of options for the house, but going with the house may leave you with little legroom for the garden. Process is generative, dynamic.

Let me explain both with a career example.

In his commencement speech Make Good Art delivered to the University of the Arts Class of 2012, this is fiction writer Neil Gaiman sharing how he continually improved the form of his career by paying attention to the context:

Something that worked for me was imagining that where I wanted to be – which was an author, primarily of fiction, making good books, making good comics, making good drama and supporting myself through my words – imagining that was a mountain, a distant mountain. My goal.

[...]

And when I truly was not sure what to do, I could stop, and think about whether it was taking me towards or away from the mountain. I said no to editorial jobs on magazines, proper jobs that would have paid proper money because I knew that, attractive though they were, for me they would have been walking away from the mountain. And if those job offers had come earlier I might have taken them, because they still would have been closer to the mountain than I was at that time.

With a career in fiction as the form, Gaiman thoughtfully chose centers for his work—adult’s novels, children’s books, comics, movies. He followed a certain order but it wasn’t predetermined. Rather, he did next what seemed to best fit his growing body of work in fiction. At an early stage, editorial jobs on magazines seemed a good fit for him; later, he said no to the very same opportunities because his form had moved past that requirement.

Gaiman’s career path was not formulaic. It was not arbitrary either. He used a generative process to make his career path.

Using a career template

Before we unpick the process of generating a career path, let us first see how we approach our careers.

Typically, we find ourselves in situations where some context has been understood and some generic arrangement of the salient elements of the form (centers) has been designed in reaction to that. Such that every time this context crops up, we can fit it more or less with this pre-decided form.

In other words, we lean on templates.

Using templates — or patterns as Alexander calls them — may be useful to tackle solved problems.

👉Here’s a template to log all details about the new product or feature.

👉Here’s a sixty-day weight-loss regimen for your body type.

👉Here’s a successful form that matches your context so that you don’t go reinventing the wheel.

But your career is not a solved problem. Your context—your character traits, strengths, interests—is unique. The reality about it is separate from everybody else’s.

Which brings me to the other disadvantage of looking for templates. Sometimes you may be given something that doesn’t fit the template and instead of thinking about what you could do with it (in a kind of iterative process) you may just reject it outright and demand that you be given something else. Deep down you don’t think you grasp your context to a level where you can design adjustments to the form put in your lap.

“I’m in the early stages of my career. I want a boss who can mentor me and really propel my growth trajectory, not one who doesn’t have weekly one-on-ones.”

“I want to find myself a big and complicated project that will elevate me to the rank of [so-and-so]. I don’t have the time to climb the ladder incrementally.”

“I want to do something in product. That’s where the biggest projects are and anywhere else would be like working in the shadows.”

Each of these statements seems like sound thinking. Except there’s no guarantee things will pan out exactly as you think until you’ve brought your context to the surface. There’s no surety that you will enjoy the micromanagement that comes with working on big, complicated projects, or that you will enjoy the process of moving people to action across functions that product people must do.

There’s no certainty because you haven’t yet defined the struggle you’re facing today. You have started with the form and assumed that you got the problem.

If one way you may miss the forest for the trees is by ignoring the context for the form, you are also prone to confuse context with circumstances. You adapt the form you desire not to your context but to your circumstances. Your ambition depends on whether the market brings headwinds or tailwinds, whether your boss is a believer or a doubter in your abilities, and whether your kid will go abroad for higher education. Instead of defining your struggle simply and precisely, you tag it to any number of external forces you cannot control. And then you come up with a form that meets circumstantial demands. You place circumstances (market, boss, finances) above you (interests, inclinations, strengths).

This can be rather frustrating. In such a reactive orientation, it is understandable why the ultimate form you’re chasing is not to have to work for money again.

How we my wife nailed form-context fit in our new place

When we moved in, we didn’t know that there was such a standard as a six-foot balcony. Balconies that are less than six feet deep are hardly ever used. It makes sense: People can’t sit around a table and chat, can’t stretch their legs, keep a cup of coffee by their side, et cetera. A smaller balcony doesn’t just change the behavior of people in that space; it can render the space unusable.

Our ignorance worked out in our favor because my wife wasn’t in any way daunted by its size limitation. She went at it with a clean slate. As she started picturing how the family would like to spend time in the nook, and started putting things together, she became progressively more decisive. She needed me less and less. I really was second fiddle even on my best day.

This is what she did.

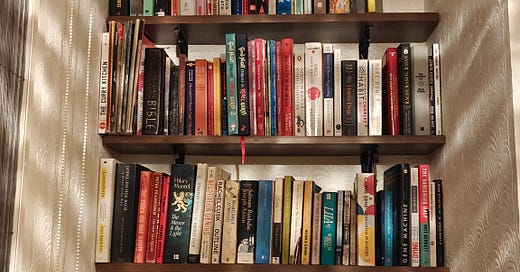

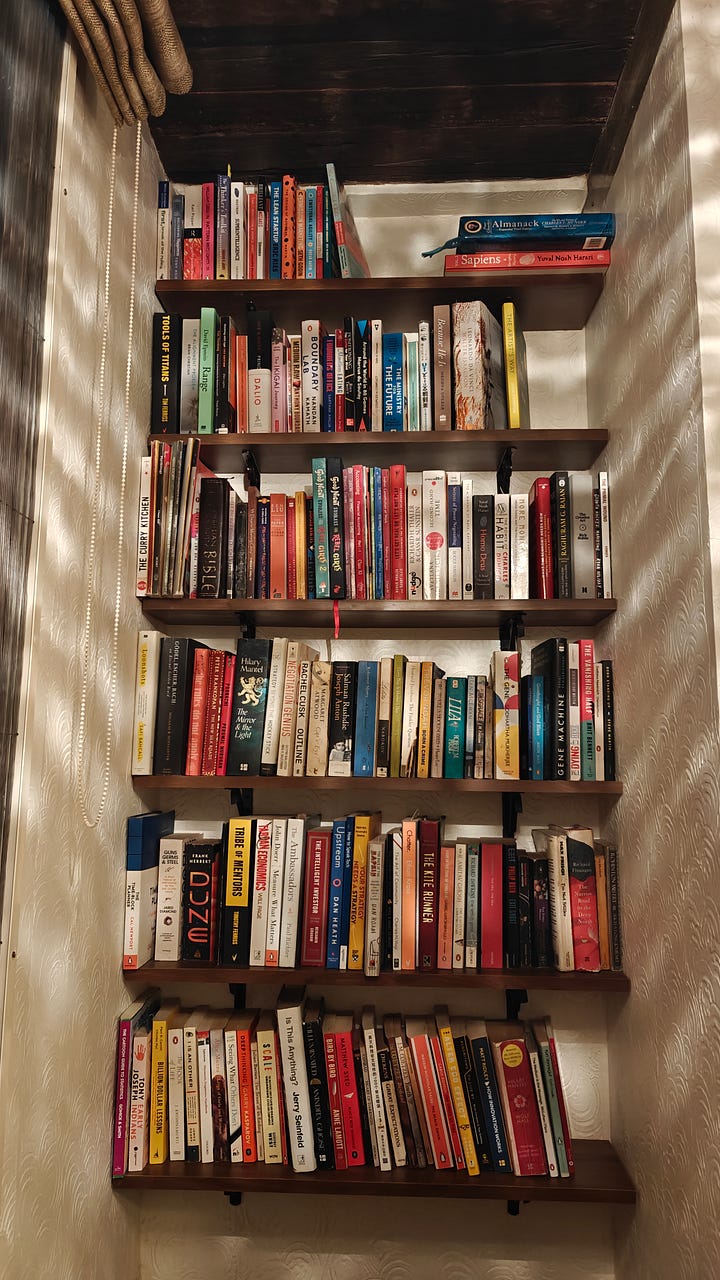

Installed some shelves for books on the more enclosed wall.

Pulled the ottoman into the balcony

Put loose covers on it

Got bolsters for each end of the ottoman

Installed a mosquito net in the sliding window

Fixed the party lights overhead

Got an adjustable reading light to stand next to the ottoman.

For each of the design changes listed above, there was a contextual discovery my wife made.

Book shelves - for easy access to books (and to make use of the more enclosed area in the balcony)

Ottoman - armless and backless, it fit the space snugly

Loose covers - open windows called for upholstery to weather the sun and wind

Bolsters - to recline back while reading, chatting, sipping a drink

Mosquito net - to do what we wanted to do without getting mauled

Party lights - they made everything look prettier after dark

Reading lights - to read after dark (the party lights weren’t bright enough)

The form we have ended up with has tremendous fit for our specific context. My wife, daughter, dog, and I love spending time in the space. Mornings are a doozy as my four-year-old and I have made a routine of watching the sun come up from behind the palm trees on the facing street.

The form has allowed us some serendipity – fun things we hadn’t thought of:

It is always fun to holler from above at house guests walking into the compound and watch their reactions; equally fun to watch people doing quirky exercise routines on the street

My daughter hangs her legs out the window and stares out as we play “I spy…”

I’ve discovered that I’m a sucker for natural light. For hours altogether, I am happy to abandon the study table we had gotten custom-made as I sit by the window and write on my laptop.

Take this particular form to a different context and it would have been much less fun. The previous tenants had toddlers whom they wanted to keep away from the balcony for reasons of safety, so they kept the window shut at all times. None of the behaviors that make the place come alive for us were meaningful to them.

Unlike in a balcony where we have a fair idea of how we would like to spend our time, for our careers, we are all foggy in the head. Do we like working with people or by ourselves? Do we like meetings or working async? Are we better at ideating or executing? And so on the questions continue for which we don’t know the answers.

The process of career design is the course of arriving at these answers, much less at some arbitrary destination like net worth or designation or size of P&L managed.

Designing for (more) life

Alexander says that the goal of the design process is to maximize the amount of life in the world. I’m down with this. It lifts the conversation from the weight of the baggage of money or accomplishments or other currencies of utility.

The most pertinent definition of success is how well the form fits the context. Through this degree of fitness, we can aspire to experience varying depths of life around us. What this suggests, in the words of Henrik Karlsson, another student of Alexander, is:

The useful thing about defining good design as a form-context fit is that it tells you where you will find the form. The form is in the context.

[...]

If you want to find a good design—be that the design of a house or an essay, a career or a marriage—what you want is some process that allows you to extract information from the context, and bake it into the form. That is what unfolding is.

Let’s go back to my wife’s process.

She didn’t make all those design decisions at once. With every design decision she made, she experienced the results of her choice, which she took as feedback. With each iteration, the image of the form unfolded by one more piece. In tandem with her growing awareness of the context, the form-context fit improved.

Most of us do not allow ourselves to imagine our careers in this fashion. Specifically…

There’s too much rigidity in our approach

Our form is largely ignorant of our context

Here’s a rough process to follow for career design:

Frame the design problem in terms of the context you want. Start with you—who are you, what you like, what you don’t like. Avoid ideals of how you’re supposed to be. They’re unhelpful because they may not be true to you.

Define the hierarchy of elements (what matters to you in terms of what you want from the career) and the relationships between them so as to characterize a coherent structure.

Get to this coherent structure through a step by step process of unfolding where you pick problems to solve in a manner that expands optionality for you and moves you forward toward your end goal, not push you into a corner or hold you back (think of Neil Gaiman’s example)

Avoid splitting hair over all the details that you don’t understand at the beginning. (When we try and make a blueprint for something as complex as a career from the get go, we will make something that won’t work in reality because we don’t have all the variables and all the interactions between them in our heads.)

Here’s what is most singular about your career. At work, you may be either the designer who comes up with requirements or the builder who executes against the requirements. But for your career, you’re both the designer and the builder. During the early part of your career, you may have experienced the frustration of not having the permission to use your judgment as you execute against on-paper requirements.

Well, when it comes to your career, the builder in you may feel the same bewilderment at the arbitrary-ness of what you’re doing — only it has no one else to point fingers at. This happens when the designer in you hasn’t given the builder in you permission to explore the context. The designer simply has dumped a static blueprint and coerced the builder – by manipulation of willpower and fear – to deliver against it. Such a form – your career – is context-agnostic. You cannot identify with it. It hurts you to claim it as yours.

The designer in you should instead be able to define and differentiate the context clearly enough to give the builder the freedom to generate one of some number of possible designs that are going to offer the best fit based on actual ground realities that become apparent during building (and not before).

Final thoughts

When imagining your career, it’s a myth that you must know exactly the form you’re looking for before all else. You could do much worse than knowing your context well enough to have a compass-level feel for the directions worth pursuing. The goal isn’t to get to a fixed form. It is to savor the process of unfolding. In the end, the design of your life may take you by surprise, yet it will fit you.

This is no optimization thinking. It is a fundamental shift in your life’s orientation. You are not as much searching for a way out — out of the rat race, out of the roller-coaster, out of the struggle that is your work — as you’re looking for a way in — an entry into a way of living where creating something better is natural and not an imposition.

👋Hi! I’m Satyajit and thank you for reading my work. Writing is the main medium of creation for me. I also use my skills as a decision-making trainer to help create leverage in my clients’ careers and as a coach to create shifts in perspective in my clients’ lives.