#194 - How come standing your ground feels like just standing to a few and impossible to most?

The difference between the reactive-responsive and creative orientations

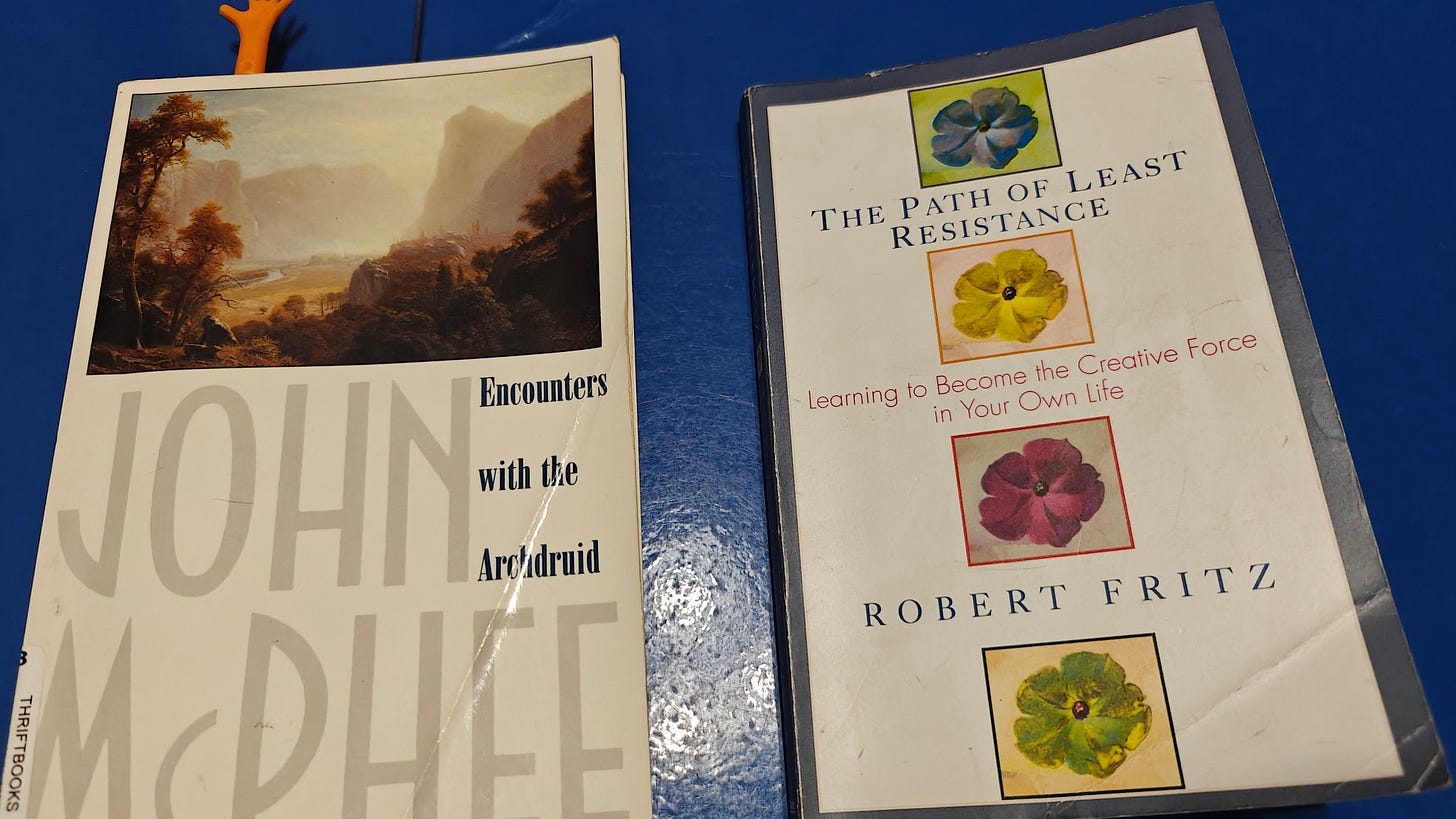

Two of my newly deepening areas of interest are structural dynamics (the study of how the underlying structure of our lives determines our behavior) and longform profile writing. Of late, I have found these two paths converging without any effort whatsoever on my part.

A discovery I have come to is that generally those profiled tend to be provocative, and provocative in a particular way. These are not perfect people, not by far; rather, they live as people whose purpose is so singular it is resplendent even as mere words on the page, certainly for my sensibilities.

These subjects tend to have a gravity around them that sucks nearly everything around into its orbit. This force makes the world dance to its rhythm, not the other way round. Circumstances no longer call the shots, like they do for the rest of us; it is these forces of nature who pluck from the grip of circumstance the fragments of the dream they’re obsessed with.

One such character is David Brower. From Encounters with the Archdruid, published in 1971:

Once, when Brower had driven for several hours through wretched fog and rain to attend a meeting and make a speech in Poughkeepsie, I asked him if he could say why did all this, and he said, “I don’t know. It beats the hell out of me. I’m trying to save some forests, some wilderness. I’m trying to do anything I can to get man back into balance with the environment.

David Brower is a conservationist, described as “the most effective single person on the cutting edge of conservation in this country [USA]” and, at the time, leader of a conservation organization called Friends of the Earth.

“I’m trying to save some forests, some wilderness” belies conditionality in the manner of “The outcome of my efforts are subject to circumstances over which I’ve no control.” Except that there’s nothing conditional about the actions of David Brower. He simply does whatever it takes for him to move closer to the metaphoric mountain of wilderness conservation and, in this particular profile, the physical mountainscape of Glacier Peak Wilderness in Washington State, USA.

This we can be sure of thanks to the account of writer John McPhee who accompanies Brower on a backpacking trip through Glacier Peak Wilderness, in which is contained a copper lode half a mile from side to side that the conservationist reiterates should not be mined.

Jousting with Brower is Charles Park, geologist and mineral engineer who “believes that if copper were to be found under the White House, the White House should be moved.”

Park is a funny fellow. In 1956, he asked to be left in a remote part of Gabon on the west coast of Central Africa, where equipped with a compass he walked for two weeks through dense jungle.

Park had had serious back trouble for some time, and one day he fell to the ground and could not get up. He lay there for two hours until something jelled, and he got slowly to his feet again and moved on. He was hunting for iron, and he found a part of what is now called the Belinga Deposit.

This is not a particularly odd two weeks in Park’s life. His life is a series of such fortnightly wanderings, alone with his frying pan and tin cup and the occasional compass.

Think of David Brower and Charles Park. Consider these two characters. The most grueling of experiences for them is part of the deal. What is this deal? Enter structural dynamics.

Robert Fritz who has developed the principles of structural dynamics believes that most of us don’t believe we can create the results we want in our lives. We compromise on what we want without even realizing it. We choose goals on the condition that they seem possible at the moment of deciding. He calls this mode of operating the reactive-responsive orientation. The orientation of the creative, in contrast, propels those of that persuasion to create what they want to, not in reaction to their circumstances but independent of them. Fritz writes:

On days filled with the depths of despair, they can create. On days filled with the heights of joy, they can create.

A trait of those in the creative orientation is that they create things—big, impossible things—because they “love it enough to see it exist.” Fritz could well have had Brower and Park in mind while writing this.

When Brower was a year old, he fell off his baby carriage on the sidewalk and shattered his front set of teeth while also damaging his gums.

His second set of front teeth did not come in until he was twelve, and when they did they were awry. He was ashamed, embarrassed, unsure of himself, shy. He was afraid to smile. In school he was known as the Toothless Boob.

Partly, from the resulting withdrawn life emerged the fervor for conservation, his life’s project. As an adult, Brower was not known for his smile. It is safe to assume that the embarrassment shadowed him his entire life. But that didn’t get in his way. It didn’t matter.

For most of us–you and me–our love for what we do is tied to circumstances. What is the point of loving something deeply if the outcome we create is tied to our circumstances? In light of circumstances…

I cannot go to college.

I cannot expect to be healthy.

I cannot be in a happy relationship.

Believing any of this is nothing unusual for us because that’s how we have been conditioned all our lives. We’ve heard from parents and elders, again and again, “you can’t have anything that you want.” Now we’re only manifesting that belief.

Brower and Park have found a way to make extreme objective discomfort palatable, even enjoyable, because it is in the service of something bigger, something meaningful. Such a vision for one’s life has the power to keep at bay feelings of powerlessness against circumstances that we experience and to chart out the path of least resistance to our most cherished goals.

PS: The title for this piece is inspired by this quote by David Brower: “Polite conservationists leave no mark save the scars upon the Earth that could have been prevented had they stood their ground.”

👋Hi! I’m Satyajit and thank you for reading my work. Writing is the main medium of creation for me. I also use my skills as a decision-making trainer to help create leverage in my clients’ careers and as a coach to create shifts in perspective in my clients’ lives.