#193 - A Ph.D. is just a sign of docility

Why are we so obsessed with the means when the end is not clear?

From a 1993 New Yorker profile of Ricky Jay, whom the writer Mark Singer anoints as “perhaps the most gifted sleight-of-hand artist alive”:

Jay wrote much of Learned Pigs while occupying a carrel in the rare-book stacks of the Clark Library at UCLA. At one point, Thomas Wright, a librarian at the Clark and a former professor of English literature, tried to persuade him to apply for a postdoctoral research fellowship. When Jay explained that he didn’t have a doctorate, Write said, “Maybe a master’s degree would be sufficient.”

“Thomas, I don’t even have a B.A.”

Wright replied, “Well, you know, Ricky, a Ph.D. is just a sign of docility.”

The late Jay was a savant obsessed with both the study and practice of magic, sleight of hand, trick shots, and other arcane subjects. His book Learned Pigs & Fireproof Women was hailed by fellow stage magicians Penn and Teller as “the most brilliantly weird book ever.” His magic shows left people, as they did to me, picking their jaws off the floor. Jay was so serious about his education that he went to five different colleges over a period of ten years, ultimately not graduating. When Jay was not switching colleges, he learned by hanging out of the pockets of the best up-close sleight-of-hand artists at the time, such as Dai Vernon and Charlie Miller.

I’m not eulogizing autodidacticism though I’m sentimental toward those self-taught. This piece is about means and ends and how — unlike Ricky Jay — many of us confuse the two.

What I have learned about means and ends that applies to individuals and companies

Last month, a client approached me for help in making up her mind about doing an MBA. Why did she want to do an MBA? She came from an orthodox family and an MBA — or, in much broader terms, higher education — was a reliable way to escape the grip of conformity closing in on her, which included marriage and domesticity.

Some months back, I had heard Santosh Desai, social commentator and ad man, talk about his experience of finding a university in Kurukshetra in Haryana where women postdoctoral candidates easily outnumbered their male counterparts. This in the state that has the worst gender ratio in the country? How so? Desai discovered that to these young women a Ph.D. was a ticket to get out of their homes and stave off marriage for a few years at least.

What these women have in common is a desire for freedom, and they have in their own ways chosen education as a path to that. The means and ends are clear. What about the rest of us? You and me, for example? How do we make life choices?

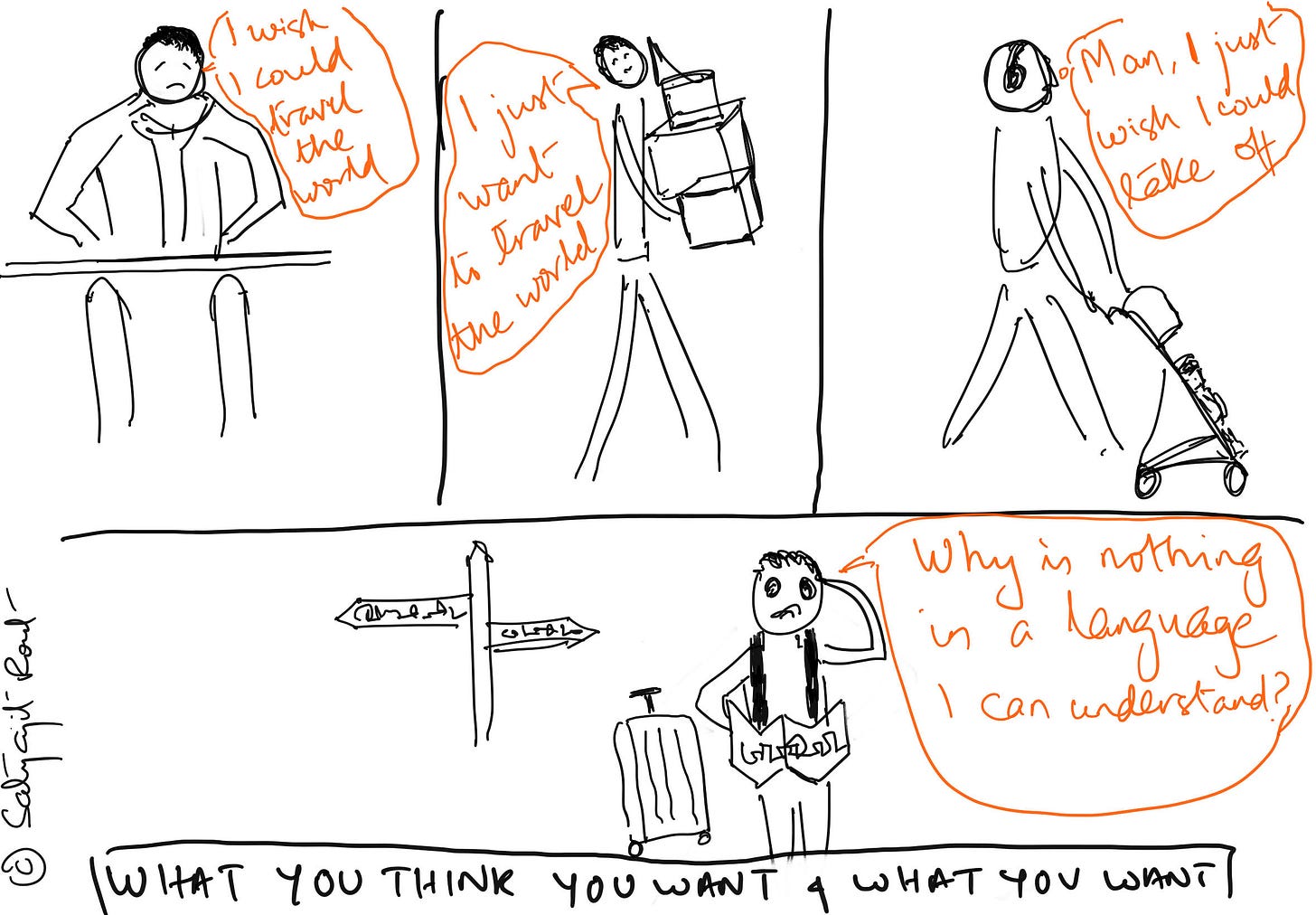

People will talk about, in response to the question of what they want, not the end result we want but the means to that end.

I want money. I want a better role. I want a promotion.

Ask them if this is a step towards some other, bigger result and they may look puzzled. What do you mean, they will ask back? This is the role I’ve been coveting for the last year. Or, isn’t money enough? What more can one want?

In truth, they don’t know what they want. A week after they finally bag that cushy VP role they’ve been eyeing since the last Olympics, they realize something new is missing in their formula for happiness. Then they may start looking at the Senior VPs in the conference room.

When making choices for organizations, the situation is only slightly different.

I heard someone high-up organizationally declare the other day that they wanted to build a marketplace that runs on user-generated content (UGC). I can imagine the ensuing conversation.

How will UGC change the future of your org? We think it will help with customer retention. What will retention do? It will lower customer acquisition costs (CAC). What will lower CAC do? Improve the bottom line. What will that do? More profits will help us remain independent and choose to be the kind of business we want to build forward. Ah!

There may appear to be a dozen beads that need to be strung together to produce a necklace worth wearing. But, looking forward, these execs don’t know that for sure. So they mix up what they want with what seems possible at the moment. Hence, a marketplace that runs on UGC.

In trying times, companies tend to face two alternatives. Work toward what you truly want or pivot to what seems possible. Most companies do the latter. Often because, just like most of us, they don’t know what they want. They only know what they want that seems realistic. They only know the means.

The simplest explanation for the success of Tesla and SpaceX is the separation of what the founder wants from what seems possible at the moment. Sometimes, what you want may seem impossible at the moment but that is not a deterrent if what you want is truly life-defining for you.

Being clear about the end result we want is a process that we too frequently don’t subject ourselves to. At one level we lack the courage to admit, even to ourselves, what we truly desire. It doesn’t seem realistic to accommodate the thought that we want to build a multinational organization or cure cancer or travel to another planet. At another level, we just don’t know. We have been working with means for so long that we’ve never really questioned the end result.

Building the vocabulary for means and ends

If organizations use sophisticated language to justify their means-focused choices, individuals lean on sensible-sounding words. In conversations with clients, some that I have heard are conscious and unconscious goals and short-term and long-term goals. Oftentimes, there’s a separation made on the basis of awareness or time. Probe it and you may hit confusion. The client will say the short-term is a bigger priority for me now; let’s focus on that first.

Recently, I learned the vocabulary to pinpoint this too-common predicament of means masquerading as empty ends. In his book The Path of Least Resistance, Robert Fritz talks about primary and secondary choices.

A primary choice is about some result you want in itself and for itself. It is not something you want because it will lead you to something else—even though it may.

👉Being able to build a self-sustaining business may bring an entrepreneur a deep fulfillment independent of circumstances.

👉Freedom to live their lives outside of rigid societal expectations may lead those female postdoctoral students in Haryana to meaningful discoveries about themselves, regardless of what it is.

👉Ricky Jay wanted to educate himself on all things magic. That education led him to a career as an actor, writer, and stage magician of pedigree, but just that education was immensely satisfying in itself.

And then there may be many things we may choose to do to make the thing we really want come true.

A choice that helps you take a step toward your primary result is called a secondary choice.

👉Taking steps to run your business profitably is a step toward independence.

👉A Ph.D. is a step toward self-reliance.

👉Hanging out with masterful sleight-of-hand artists in his formative years was a step for Ricky Jay toward mastery of his craft.

Some of these secondary choices may be things you would not do outside of the context of the primary choice. Some of those postdoctoral students, I would imagine, perhaps preferred not to pursue a Ph.D. but they did so anyway because the choice made the most sense in the service of the bigger pursuit of freedom.

Dealing with conflict between primary choices

A primary choice sets you up to create a specific and meaningful result you want in your life. Sometimes, two such primary choices may appear to come in conflict.

Your desire to eat healthy and to do your best at work may seem to be at loggerheads during a particularly busy time at work where you are traveling a lot and it is hard for you to stay on top of your diet. When such a situation comes to pass, you typically feel guilty one way or the other—guilty about not following a diet or about compromising at work. You may feel a sense of powerlessness and blame circumstances for your decision, whatever that may be. Instead, Fritz says, “you as creator [can] determine the hierarchy of importance among results.”

If sticking to your meals is your primary choice (hence non-negotiable), then arrange your work around it (the secondary choice, and hence negotiable). In setting up this hierarchy, the word sacrifice doesn’t rear its head. Choose what is more important to you and align your actions to support that choice. “Making strategic secondary choices is very empowering,” assures Fritz.

A glimpse of this apparent conflict between primary and secondary choices can be seen in the following excerpt from the New Yorker profile on Jay:

His friend T. A. Waters has said, “Ricky has turned down far more work than most magicians get in a lifetime.” Though he earns high fees whenever he does work, a devotion to art rather than a devotion to popular success places him from time to time in tenuous circumstances.

The man refuses money on the table because he has a vision for the practice of his art. That is his anchor. All other choices–the decision to refuse well-paying gigs, for example—are subordinate to this mainstay. Notice the writer’s interpretation of Jay’s circumstances as tenuous. Does Jay feel this way? Sure. Is he bothered? Perhaps to the extent one is bothered upon discovering that the theater has run out of popcorn at the screening of their favorite movie.

This is not new to you

On August 14th, I had written:

Most people, if you ask them what they want, will share a specific manifestation of their vision. They may say, I want to wake up early.

Ask them what experience they want to have as an early riser and they may describe feeling productive. Ask them how else could they get the same feeling and they will start to think…

“maybe I can stop watching Netflix with lunch because I tend to not stop in the middle of an episode”

“maybe I will not check my email before going to bed because it stresses me out”

Then they may realize that any of these things are much more doable for them than all the things they have tried and failed—meditation app, set an alarm, early dinner—to get up early.

Don't go by what people say they want. That's often a proxy.

Ask them for the experience they want. That's the true reality they want.

And by the way, some desired manifestations are too common:

I want to retire at 40.

I want to travel the world.

I want to live on a farm.

There's a unique experience hiding behind each of them.

As I peruse this note, it appears to me that I have been thinking about primary and secondary choices even before I had the words in my lexicon. I’m also encouraged to believe that you too, dear reader, fundamentally understand the idea behind means and ends. If this piece helps put words to what’s been running in your head, then I’m happy. My job is done. For those more curious, I encourage you to get your hands on a copy of Fritz’s The Path of Least Resistance or read any of his later works. I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time doing so this past month and I’m energized.

👋Hi! I’m Satyajit and thank you for reading my work. Writing is the main medium of creation for me. I also use my skills as a decision-making trainer to help create leverage in my clients’ careers and as a coach to create shifts in perspective in my clients’ lives.