#186 - A better manager: wins an argument or finds the best argument?

The relationship between inquiry and advocacy for a manager

In hierarchical organizations, the way young managers learn their trade can prove to be severely detrimental to their learning and impact later on as they move up.

The hallmark of top-down decision-making, as is common in traditional command-and-control organizations, is that decisions flow down. Decisions are made at the very top and these decisions get pushed down through managers. This is called advocacy. Think of managers as advocates arguing for their positions.

At every level, managers are rewarded for advocacy—for getting the troops aligned, for getting things done. If you’re getting a whiff of the military in all this talk about command and control and troops, you have a good nose on you. This direction of flow of information is most common among defense forces. Such a method works well if the decision being imposed is obviously right or if there’s absolutely no time to be collaborative.

In business, I cannot argue that either of these two conditions is the norm. The biggest business decisions are big because there’s uncertainty. Reality is complex for even the most experienced minds to simplify into reliable mental models. Something almost always gets lost.

It would help decision-makers to be able to tap into the wisdom of the collective. To see what others see and to tease out assumptions in their own thinking. That’s not how command and control works, though. The more contentious the decision, the more they push managers for advocacy. The ones who can bring order in such chaos are rewarded down the line.

Before we go into the consequences of this behavior, let us understand it.

The story of the world-class advocate

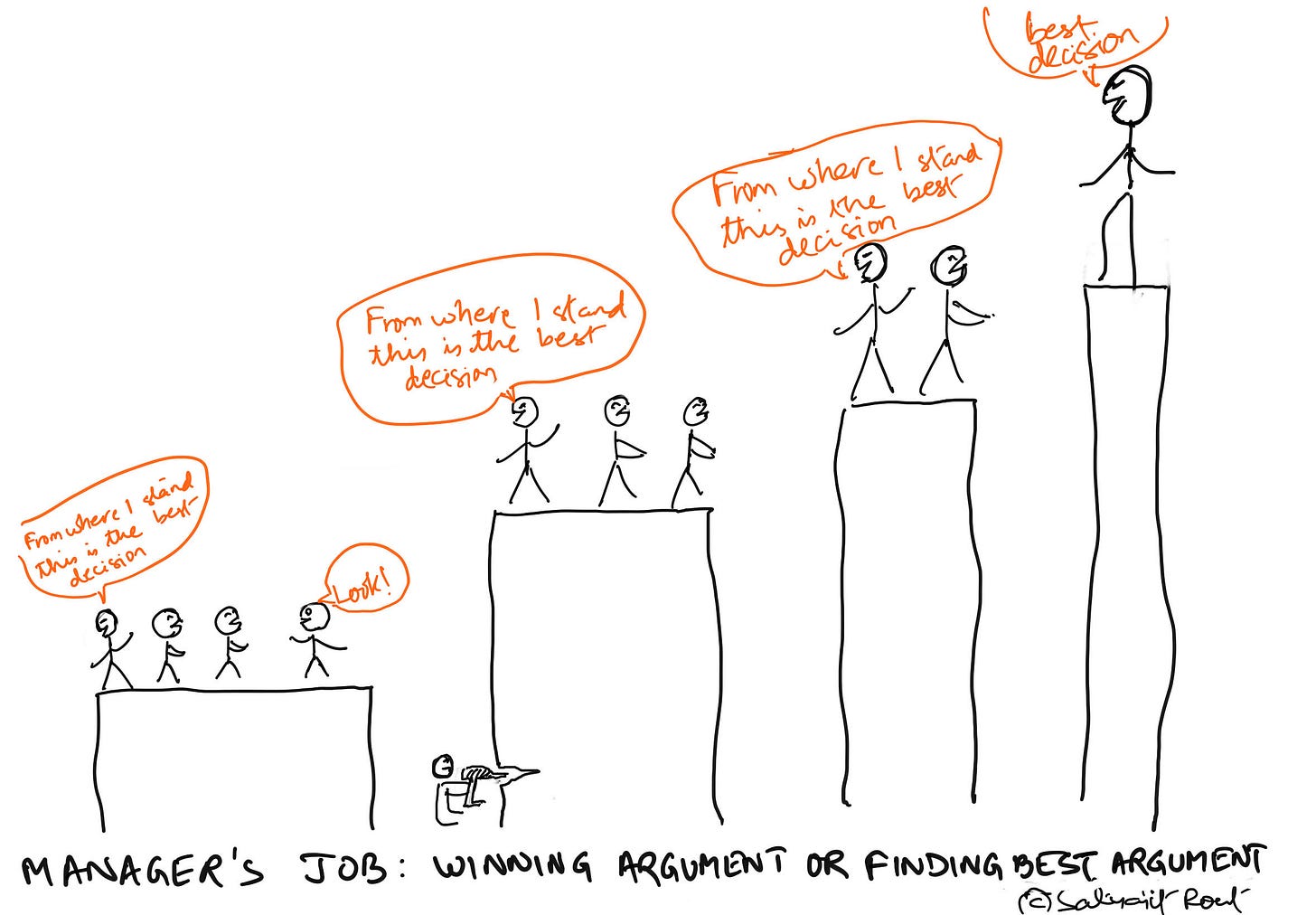

Every manager has two jobs: win arguments AND find the best arguments.

A manager needs to bring clarity to situations. That she does by settling arguments. The manager picks the winner, people know what to do, clarity leads to action.

She also needs to find the best arguments—the ones that hold up to scrutiny, the ones with the least shaky assumptions. No argument may be perfect, yes, but some are better than the others. The manager needs to find the best one.

Both contributions are necessary. Do only one and the balance goes off.

When a manager starts to push an argument down the throats of subordinates, because she’s pushed by her higher-ups who in turn have been pushed by theirs, here’s what begins to happen, first slowly then swiftly.

Let’s say you’re the pushy manager here. You realize that convincing people by winning arguments is tiring. The more you push for a position, the more someone in your team pushes back. It would be so much better, you wonder, if I could convince without having to argue. So you start to selectively share the data on which the decision is based. You see that it immediately cuts down the resistance. It shortens those interminable meetings. Now you’ve got a taste of the magic pill. Soon, you’re hiding important context, adjusting the impact of the decision to your advantage.

With each iteration you get better at winning arguments by suppressing them. You don’t have any nefarious objectives. You’re just choosing the path of least resistance. You’ve discovered a philosophy superior to “disagree and commit.” You call it “(make them) agree and commit.” You love the name but you don’t want to be vain so you keep it to yourself.

Anyway, your results are noticed in the upper echelons. You’re a world-class advocate. Your career thrives. This much is obvious.

Away from all this glitter, some mold has started seeping into the walls. Your habit of not sharing your assumptions or inviting and considering alternative viewpoints means you don’t learn anything new about any situation you’re trying to help your team navigate. You start taking your opinion seriously, treating them increasingly as facts.

As your career thrives and you move up the chain, the situations coming your way get more complex. There are no easy choices. What the! Why didn’t anybody tell me about this? Even if you wanted to, your reputation is like this giant wall blocking questions from your audience. Plus it’s a tad embarrassing for you at this advanced stage to seek help. Even if you managed to somehow swallow your ego, you realize you do not have the skills to facilitate collective inquiry and come up with solutions that are better than any one individual’s.

How to find the best arguments

1️⃣ State your assumptions openly and clearly.

2️⃣ Show the data or observations on which your assumptions are based.

3️⃣ If there’s a line of thought between the data and assumptions, show that as well.

If you noticed, none of this digs into what others are thinking. But you need to do all of this. Think of it as a cover charge for the Club of Open Conversations for the Purpose of Finding the Best Arguments. If you do not show your cards and simply ask people to show theirs, you will tick them off and curb them.

Now it may also seem like you’re throwing the conversation too open with steps 1-3, but if your reasoning is solid, you’re actually making a strong case without having to throw your weight around.

Now that you’re in the club and people see you as an equal, you can start looking for what you may have missed in your thinking:

4️⃣ Ask your team to give their views. Encourage them. Give them a nudge. [Don’t fake-ask questions just to show that you’re interested. People can see through such overtures.]

5️⃣ Once they do, tell them what you think of their opinion while also sharing your assumptions about it.

It’s possible after such giving and taking, you may come to an impasse. Push further here and typically you get resistance or acquiescence. Probably not the truth. To break the deadlock, I suggest picking one of the competing options and asking Roger Martin’s magic question:

💡What would have to be true for this to be the right choice for us?

As Martin says, now you have redirected collective energy from defending to exploring. Once you have set people’s brains ticking, you can now ask them about how they may get to the deadlock-breaking data, what experiments could they design for new information.

It is imperative for managers and leaders to have the ability to advocate for their positions or else no action would ever materialize. By dint of authority or by incentives, managers tend to do this reasonably well. What they don’t do as much and are not as good at—the focus of this piece—is the skillset to do inquiry.

Pairing advocacy (the skill to win arguments) with inquiry (the skill to find the best argument) is what can make you stand out as a leader among peers and earn the respect of your team. And in life, it will make you more empathetic to those around you.

👋Hi, I’m Satyajit. Thank you for your time. I’m a decision-making trainer and coach. I write about better thinking at the intersection of business, career, and life.