#185 - Home truths about the Tightwad Employer

When the employer supports employees strictly conditionally (Part 2 of 2 on employee-employer relationships)

Around 1980, a group of CEOs started meeting regularly at MIT with the intent to figure out a better way to run organizations. William O’Brien, one of the members of this elite group and CEO of Hanover Insurance, had some out-there ideas about organizational change.

One of O’Brien’s ideas was around employee development. He believed that supporting employee personal growth was aligned with organizational success. There was no tradeoff, no balance needed between the two. The more an organization invested in its employees’ personal growth, O’Brien believed, the more initiative the employees took in return and the more committed they were to the work and the more the organization benefited from such employees.

(Note: Here’s the employee perspective to help you see the question of mutual commitment/exploitation from the other side.)

This is not the norm, as you perhaps already are aware.

Peter Senge writes in The Fifth Discipline:

Traditionally, organizations have supported people’s development instrumentally—if people grew and developed, then the organization would be more effective.

The word instrumentally sticks out on first reading. It suggests conditional support. But it doesn’t sound like a problem to me. An organization runs on many engines. You need fuel for each of them, so you got to make sure you pour more fuel into whichever engine’s giving you the most mileage. If the M&A engine runs longer than the people development engine, then more power to M&As.

Here’s where the analogy breaks. People are not engines.

A senior exec at an ecommerce brand once told me about his new boss who flew into a rage when a longtime vendor initiated termination of its contract with the organization. The contract was drawn up years back and had a notice period that was far too short for the company to find a replacement in. The boss, who had no relationship with the vendor, thought it fit to call all the suits in the firm to pore over the contract for loopholes to exploit. With that one move, he raised the stakes in a way that made it hard for things to go back to a place of mutual trust.

I don’t know how it ended but I know that if you deal with people like they’re contracts—if you point them to legalese when you want things done your way—they will remember the bitter aftertaste of working with you. And they will give it back your way. You may still come out trumps but you will lose a partner, a collaborator, a vendor for good.

Sometimes, organizations develop a learning disability. There are several reasons but one of them that is peculiar to collectives such as a firm is that management changes. One crop of personnel doesn’t stay long enough to harvest what they have sown, and what they have sown in turn was probably contingent on the previous harvest. In the short-term a hard-nosed move like going legal with a vendor may seem to make a point, by showing up on the bottom line; over a longer period, it erodes commitment and provokes fear among vendors, partners, and employees. As an employee, you wonder what’s stopping such a thing from happening to you.

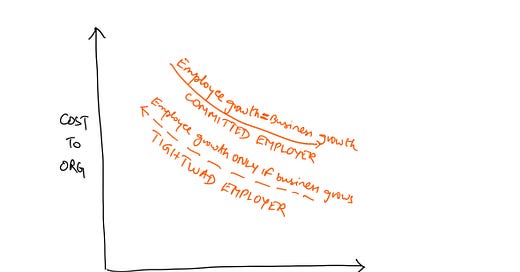

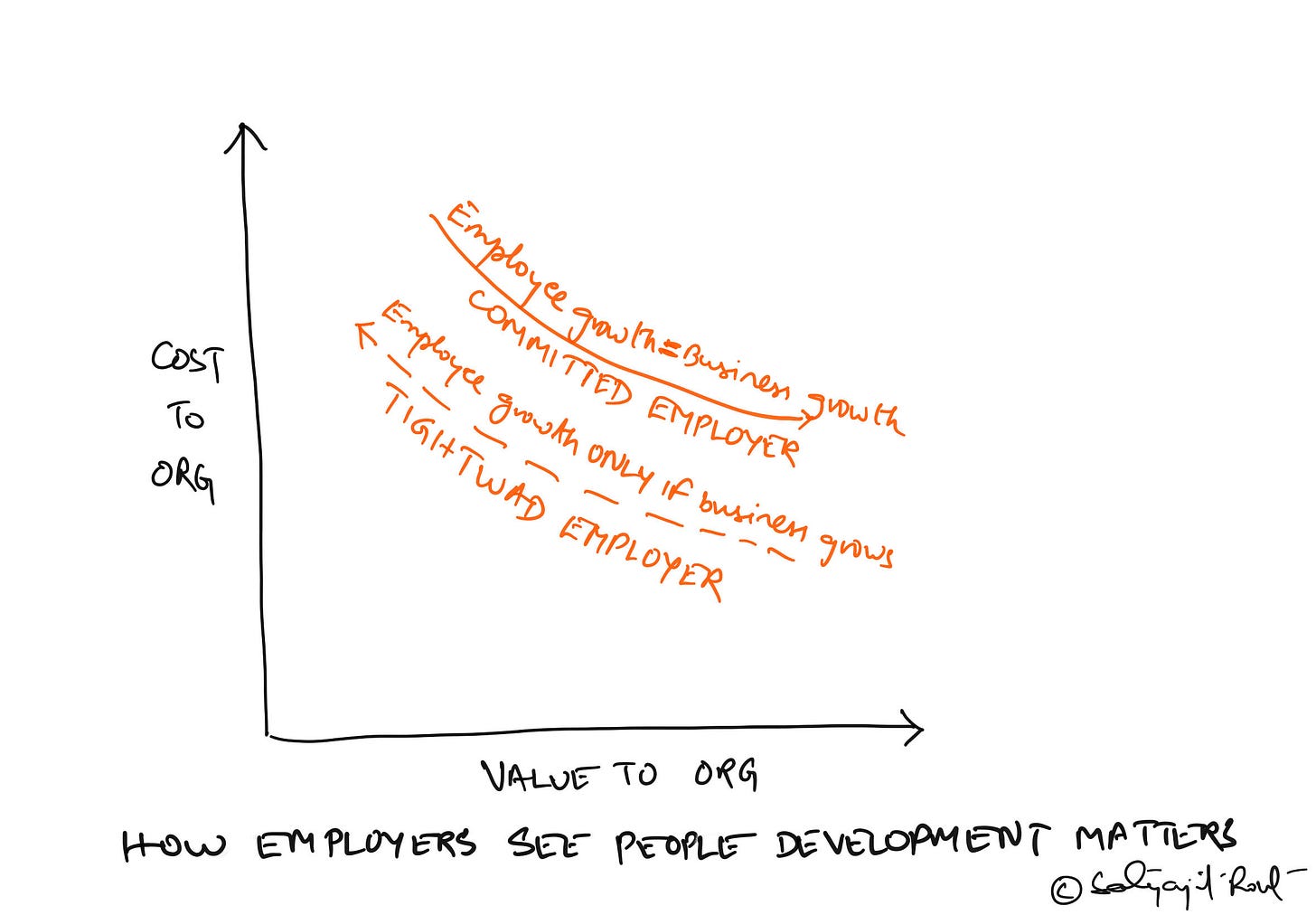

If one were to plot the value to the organization and the cost it incurs because of its greedy miser tendencies, this is what the shape could be like:

Senge quotes another CEO from the group that met regularly in the 1980s. Here’s Max de Pree from Herman Miller:

“Contracts,” says De Pree, “are a small part of a relationship. A complete relationship needs a covenant… a covenantal relationship rests on a shared commitment to ideas, to issues, to values, to goals, and to management processes…”

This made me think about the word covenant. I searched through the archives of this newsletter—-you, dear reader, have not set eyes on the word here. I’m not bringing this up as a matter of trivia but because covenant, though a heavy word in business writing, captures what is missing. Organizations have contracts—the more, the merrier—but only rarely do they seem to believe in a promise to be committed to employees (or vendors for that matter).

A common situation we see this is during a business crisis. At the first sign of trouble, such companies cut back allocations to employee learning and development.

This is not the problem, by the way. This is a symptom. The problem is this:

⚡These organizations believe there’s a fundamental tradeoff between personnel development and business success. They believe that training employees will only make it easier for them to defect to competitors, or the delay in the learning and development ROI makes it not worth it, or that fulfilled employees are complacent employees.

An employer committed to people development may start off having to bear a high cost. As productivity swings up and new behaviors start to emerge, that initial cost starts to come down. Covenants replace contracts; conditions for mutual commitment fall off, one by one; and a new culture emerges. The learning disability worsens.

PS: I wonder what happened to the CEO collective. I did a cursory search on them but nothing came up. I would love to know more about that bunch, so if any of you readers have something for me and other readers like you, please share in the comments.

👋Hi, I’m Satyajit. Thank you for your time. I’m a decision-making trainer and coach. I write about better thinking at the intersection of business, career, and life.