#146 - Why is the quest for mastery so embarrassing?

The human cost of pursuing mastery: The hard apprenticeships of Robert Caro and Leonardo da Vinci

For about three years in my late twenties, I was my poorest as an adult. After trying various arrangements to manage a job and a writing life, I quit one of them at twenty-six.

Without a job, apart from the freelancing gigs I would take up to make ends meet, I spent my weeks and months writing a novel. I had told myself and others I would finish the book in a year tops, now that it was the only thing I did with my time, but that went out the window surely enough.

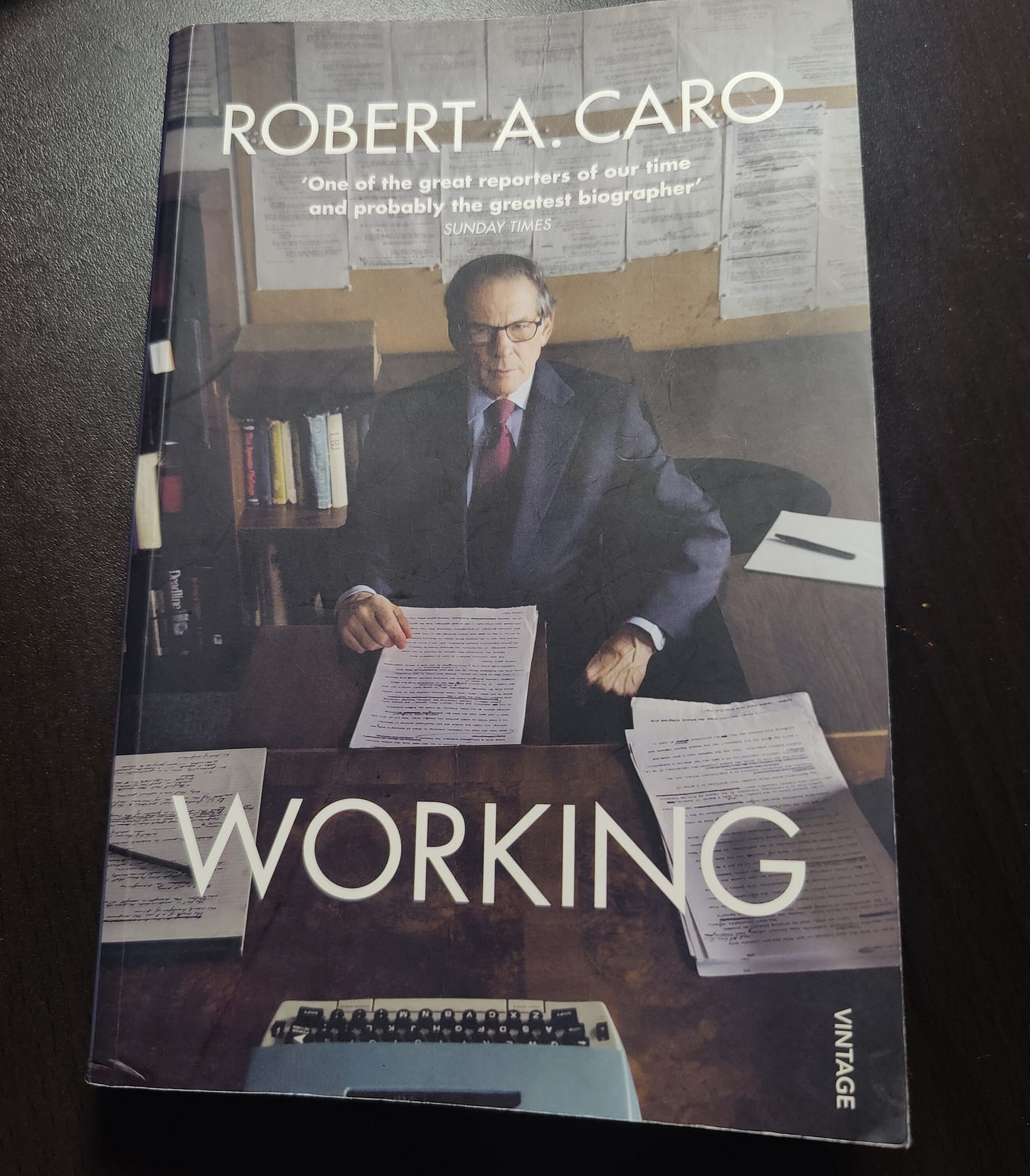

Up until this point in my life, the longest deadline I had ever managed was maybe a month. To go an order of magnitude longer tested me in ways I could not describe better than Robert Caro, recognized as one of the greatest biographers in history:

In part, this was due to the lack of any relationship between writing the book and the inescapable realities of the rest of life, such as earning a living.

There’s no examination of Caro’s life in 1971 without an examination of ‘this’—Caro’s first book project that had steadily consumed him for five preceding years. The problem is quite simple: Caro is a biographer who has a distate for telling the story of a great man. He’s only interested in investigating such a life to come closer to the answers to where does power come from, what effect it has on those it is taken away from, and what power does to those who have it.

This sweep of his vision makes for a peculiar wrinkle. Here in Caro’s own words:

While I had, in 1966, been given a book contract, the advance I had received was $2,500, and it had been spent so long ago that it seemed to have no connection with the years that had passed since I received the check. I had been a reporter on Newsday, and as Ina, my wife, and I watched our savings run out, and we sold our house to keep going, and the money from the sale ran out—and my editor assured me that while my early chapters appeared to have literary merit, there would be so little audience for a book on [Robert] Moses that the printing would be modest indeed—the book sometimes seemed more and more like a rather unreal interlude in my life.

So, in the first five years of his attempt at cutting it as a biographer, Robert Caro, who goes on to be the most celebrated of them all, has quit his job as a successful mid-career news reporter, used up half his book advance and been refused the other half, sold his house in Long Island, moved to an apartment in the Bronx his young family hates, and produced about five hundred thousand words (>10X the length of an average nonfiction book) that was still woefully short of what he could call a manuscript.

This project to explore the fundamental nature of political power by examining the life of Robert Moses, the urban planner and builder of public works who ruled over New York City for forty-four years, has wrecked the career of its biographer-to-be Robert Caro even before it has begun.

Caro’s debut project will culminate in The Power Broker, bringing him the first of his two Pulitzers and, more importantly, a respite from the hand-to-mouth existence. In 1971 Caro doesn’t know that yet. In fact, he is a few years from knowing that. What worries him is letting his wife Ina and young child Case down. What worries him is that his editor is playing truant with him. That his publisher has been steadily nudging him with alarming openness to cut his losses and get the book out.

And tussling with these aggravations are questions, unanswered questions about the fundamental nature of human power he is drawn to despite being broke and ignored. Looking back at his life, Caro suggests that his first book was as inexplicable as magic. Reading his life’s story, I get the sense that it was as intentional too.

‘Sometimes magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect,’ said Teller, half the magic duo of Penn and Teller. The quote was made for Caro. Caro could’ve written a more conventional biography, a physically lesser book than the 1,200-page gym weight he ended up producing. But he chose not to. He chose to put more into it than what anyone else might reasonably expect. He chose to pursue mastery.

master, noun: someone who has been the target of social ridicule

‘There is another reason the books take so long’, says Caro, ‘—a reason that has to do not only with my nature but also with what I am trying to accomplish with those books.’

What was Caro trying to accomplish?

For our life’s calling, we don’t decide what to aim for in agreeable consultation with friends. It’s not something we open up to casual scrutiny over dinner and drinks. We respond to the calling in the only way we can, in a manner that reflects who we are. Whatever it was that Caro was trying to pull off, he had little to show for it. From seeing his writing in print every day at the daily Newsday, Caro didn’t see a single bylined word of his for the next eight years.

I was still in the first year of research when friends and acquaintances began to ask if I was “still doing that book.” Later I would be asked, “How long have you been working on it now?” When I said three years, or four, or five, they would quickly disguise their look of incredulity, but not quickly enough to keep me from seeing it. I came to dread that question.

Instead Caro was trying to get at the question, the answer to which hid underneath these facts:

Before Caro, there had been seven biographies of late US President LBJ and none had proved if a forty-year-old LBJ had stolen the 1948 election to the Senate from the state of Texas.

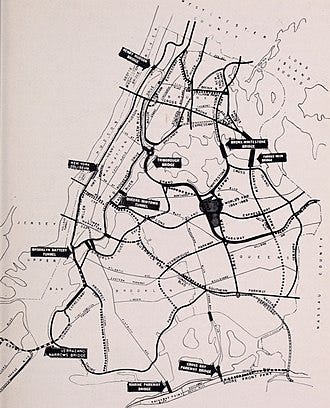

Before Caro, everybody knew Robert Moses ruled over New York City but none knew the human cost of what he had built over four decades—seven bridges, fifteen expressways, sixteen parkways, more than a thousand low-income apartment houses, and even more additional apartments as part of urban renewal programs.

Caro’s projects, first, to trace the history of a city, one as big as New York and over a period as defining as the twentieth century, and next of a country, one as big as America and at a time as momentous as the years of LBJ (1950s and 60s), whose legacy includes expansion of civil rights, health care, and public services, define ambition.

And he responded to the ambition within the only way he could. He conducted 522 interviews for his Robert Moses project and, as if convinced interviewing is his thing, did over a thousand for his LBJ project. He moved to rural Texas for three years to understand the milieu during the late President’s childhood and youth and to talk to anyone who was there at the time.

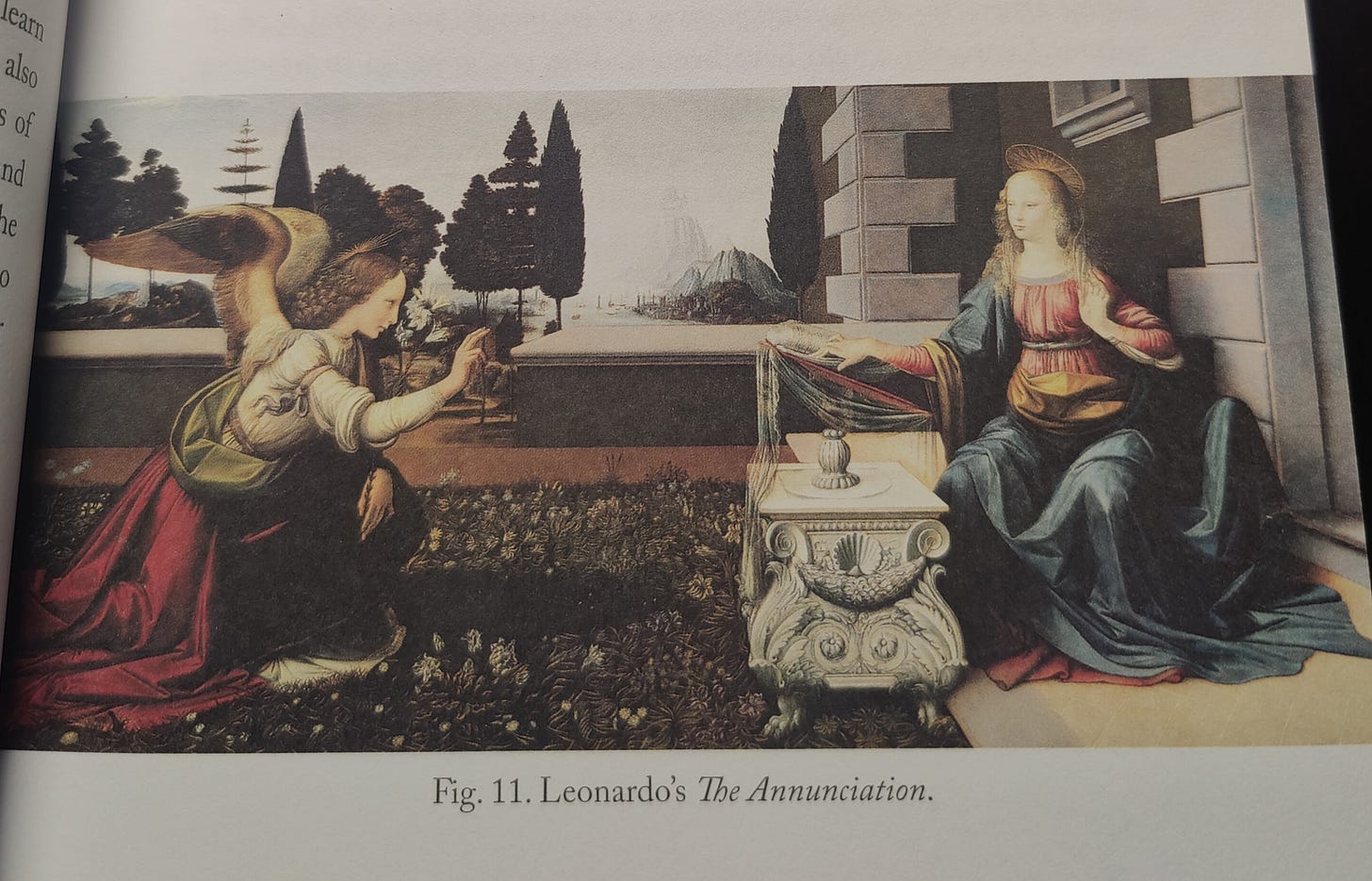

We see the same ambition in the works of Leonardo da Vinci.

After being snubbed by Lorenzo de’ Medici in his recommendations to the Pope of the finest artists in Florence who could paint a new chapel the Pope had gotten made (the Sistine Chapel), da Vinci decides to mark a new beginning. He quits the Medici patronage, leaves Florence for Milan, and begins pursuing all ‘the crafts and sciences that interested him’ without concern for the commerce of it.

Not long after this fresh start, da Vinci accepts an ambitious commission—’an enormous bronze equestrian statue in memory of Francesco Sforza’, the father of the then duke of Milan. Robert Greene writes about da Vinci’s response to the challenge:

Leonardo worked on the design for months, and to test it out he built a clay replica of the statue and displayed it in the most expansive square in Milan. It was gigantic, the size of a large building. The crowds that gathered to look at it were awestruck…

Once his clay model has been validated and people’s anticipation for the actual bronze statue has been ramped up, da Vinci invents ‘a totally new way of casting’. He decides to build the ginormous bronze horse as one piece.

Shortly after, war breaks out. The duke cannot afford the enormous inventory of bronze needed for the statue. The horse is never built.

Da Vinci’s peers manage more than a chuckle, more than once. Michelangelo, da Vinci’s formidable and much younger peer, also the one to paint the Sistine Chapel for the Pope, says, ‘You are the one who modelled a horse to be cast in bronze, was unable to do it, and was forced to give up the attempt in shame,’ and on another occasion, ‘So those idiot [caponi] Milanese actually believed in you?’

Not an easy life, da Vinci’s.

Mastery is mastering time

The beating heart of social pressure is time—time when nothing much happens, when we as the apprentice in search of an intuitive feel for our craft have nothing to show for it. Time in which our friends from high school and college have moved on and up.

In my favorite undated Internet clip, a struggling comedian is complaining to Jerry Seinfeld somewhere in the back of a comedy club. You can hear the laughs in the background. The young comic says that the last three years of his life have been a blur. He talks about the sacrifices he has had to make to make it as a comedian. He’s twenty-nine. He’s worried.

Seinfeld, perhaps in his early 40s, scrunches up his nose.

‘This [pointing at the stage] is such a special thing,’ Seinfeld says. ‘This has nothing to do with “making it.”’

‘But did you ever stop and compare your life?’ the struggling comedian asks. ‘I see my friends and they’re moving up. They’re making a lot of money. They’re all married. They’re all having kids. They have houses. They have a sense of normality.’

Seinfeld sports the face of one who has taken a bite of a cheese that’s been out too long. He says:

Let me tell you a story. This is my favorite story about show business.

Glenn Miller's [American conductor] orchestra is doing a gig...They can’t land the plane because it’s winter, a snowy night—they have to land in this field and walk to the gig. They’re dressed in their suits. They’re carrying their instruments. They’re walking through the snow—it’s wet and slushy.

And in the distance they see this little house…They go up to the house and look in the window. Inside they see this family. There’s a guy and his wife—she’s beautiful. There’s two kids, and they’re all sitting around the table. They’re smiling. They’re laughing. There’s a fire in the fireplace.

These guys are standing there in their suits. They’re wet and shivering, holding their instruments, and they’re watching this incredible Norman Rockwell scene.

And one guy turns to another guy and goes, “How do people live like that?”

That’s what it’s about.

Those who play the game of mastery use time to focus, to hone their craft, to perform a thousand repetitions, to seek simplicity in the most complex of things. Those who are after social approval and status see time as a needless decelerator that they must somehow hack.

Robert Greene, author of books on strategy and power, writes in Mastery:

To the extent that we believe we can skip steps, avoid the process, magically gain power through political connections or easy formulas, or depend on our natural talents, we move against this grain and reverse our natural powers. We become slaves to time—as it passes, we grow weaker, less capable, trapped in some dead-end career.

The struggling comedian believes he’s trapped in an unmarked tunnel of time that he has to escape. In that time he lets his Wall Street friends define success for him. Seinfeld thinks of time as a vessel that carries his deep love for his calling. He cherishes the time spent in preparation, the time on stage.

Being comedians, both agree on the value of timing yet could not be further apart on the meaning of time.

Playing the long game

Deep in the weeds while researching and writing his first book, Caro wanted just one thing—making real his vision for examining political power. About anything beyond that, he was utterly pragmatic.

I had always believed I was a writer, but to me being a real writer meant writing more than one book, and I could see absolutely no way of getting to write another one. I was determined to finish this one, no matter what. But the only future I could see after that was to try to persuade Newsday to rehire me.

After writing my manuscript for two years, I felt a weight off my shoulders the day I wrote the last page. It was a labor of love alright but now I wanted to make something of it. I wanted others to read my words and feel what I wanted them to feel, and perhaps more. So I drew up a list of literary agents—I had carefully avoided this task or anything connected to the non-writing aspects of life as a writer—in order of preference and contacted them one by one. One by one so that I didn’t say an eager yes to someone lower on my list.

I would send this, or a version of this, to a new inbox every few days:

Bureaucrat MUGUNI and his wife IRA hope to settle down with their nine-year-old son SIJAR in a starter house in a new town. But to make tomorrow work, they need to see themselves as they have not until now. Since his disappearance from the Naxal revolution, Muguni has lived hermetically. On hearing about an old comrade’s arrest, he jumps headlong into the campaign for her freedom. Ira seeks independence by teaching needlework. The arrival of a housemaid frees her. Muguni’s pursuit of redemption doesn’t last long. Ousted from the campaign and rebuffed by Ira, he assaults her, prompting her to move out with Sijar to the house of SWAMIJI, her spiritual guru. The house is no more a sanctuary: Muguni is drawn to the maid; Ira seeks refuge in faith; and Sijar befriends the neighborhood DHOBI who courts the maid. When the dhobi hears of the maid’s liaison and decides to confront Muguni, and Ira, finding Swamiji’s tutelage oppressive, returns home with Sijar, matters come to a head.

Within months—and upon being ignored or, much more rarely, rejected— I would be forced to change my strategy. I would reach out to multiple agents at the same time. Next, I would reach out to agents in India, my own country that I, in my germ of a brain, didn’t believe had an audience for literary fiction.

After a year of trying unsuccessfully to find myself an agent who would be willing to represent me, I mustered the courage to ask myself the question I had to ask: Do I have it in me to play the long game?

At the end of that year, I got married to my girlfriend of several years. Life changed. I asked myself that question again. I heard some murmurs but no clear voice.

I Benjamin-Buttoned my life, going back to a job in an exact reversal of the way I had left it (part-time quitting to full-time quitting). I sought out my old firm to re-employ me part-time. Right below the book synopsis I started adding this description, or some version of it, to let agents know I had options:

My day job in Mumbai involves working on strategic initiatives for a leading global scientific manuscript editing company.

Result? Nothing. Silence. Just the same question. Do I have it in me to play the long game? At some point, I don’t remember the day, I got my answer.

Typing out these words across my screen, ten years later, my connection to that old life feels tenuous. At the same time, reading Caro brings snatches of it back with lightning speed. By most social scorecards, I have had a successful decade since I last asked myself that question. At age thirty, I wanted a comfortable life ahead. I also wanted mastery.

In the last decade, I have, as it occurs to me, got one and missed the other. I’ve got the comfortable life. I’ve escaped mastery and, along with it, the human cost of mastery—the ridicule, the waiting, and the questioning of one’s own core.

The gravity of modern-day conveniences

For years, Robert Caro would walk into the Main Reading Room of the third floor of the New York Public Library in the morning, write down his name and the call numbers of the books he wanted on a pink slip, and wait for any of the helpful librarians on site to come to his rescue. At closing time, he would return the books he had so painstakingly obtained in the morning.

Years later, while researching LBJ, Caro would follow a similar ritual at the Johnson Library in Austin, Texas. Only there would be an appendage to his day. After the Reading Room closed, he would dash out of the library, past the Presidential exhibits, into his car, and drive out westward to LBJ’s place of birth in the Hill Country to find out what he ‘had been like as a boy and young man’.

When da Vinci was a young apprentice in the studio of Andrea del Verrocchio, he was asked to ‘paint an angel as part of a larger biblical scene designed by Verrocchio’. Among the great lengths to which da Vinci went to make the assignment his own, perhaps the most telling was buying several birds and spending several days thereafter sketching their wings such that he could make them look birdlike on the angel’s body.

Caro couldn’t Google the bowels of recorded history. Nor could he order books on Amazon, let alone ask ChatGPT. Da Vinci couldn’t subscribe to the best YouTube channels for bird sketchers. While there’s no romanticizing their everyday hardships, both had come to accept the inconveniences as an essential part of their pursuit of mastery.

Says Robert Greene in the introduction to Mastery:

Whenever we learn a skill, we frequently reach a point of frustration—what we are learning seems beyond our capabilities. Giving in to these feelings, we unconsciously quit on ourselves before we actually give up.

Technology has made it infinitely easier for us to learn anything today and at the same time exponentially harder for us to attain mastery. We’ve come to seek validation like a guided missile seeks its target. In an infinite browsing mode, we’ve twisted ourselves in knots calculating the return on investment of our time every hour of our days. During these constantly running episodes of utilitarian math, the greatest seduction is that of the cheap and the quick. This behavior endlessly reflected on social media makes us see what others around us do and lets them define success for us, trapped as we are in the fear of falling behind our generation.

It is to such a mind that the path to true mastery is frustratingly long and opaque. Even if it has an inkling about its true inclinations, that heartbeat of a signal is drowned by the loudness of distractions around. So much so that we seek guarantees that beyond the hard climb of preparation is the promised land, and receive none.

The feelings of inadequacy snowball when we see the social media feeds of our more successful digital neighbors. The tolerance for discomfort slips. We barely scrape past our apprenticeship. We give up the chase. We move on to something else the world’s touting to us.

Caro and da Vinci chose lives of focused attention over distracted scanning. It helped them that the avenues for superficial explorations were few and far between. We’re not as lucky. The biggest fears of those masters were paying too high a price for self-expression—winning life but as a Pyrrhic victory. Our generation’s worst enemies are quick wins.

Seeking mastery today

Back in 1971, admitted into the Allen Room as one of eleven writers with book contracts who could keep their desk and research materials overnight at the New York Public Library, Caro finally got over the problem of not knowing anyone else in a similar pickle as him. Here he describes his first encounter with a kindred spirit:

Then one day, I looked up and James Flexner [biographer of George Washington] was standing over me. The expression on his face was friendly, but after he had asked what I was writing about, the next question was the question I had come to dread: “How long have you been working on it?” This time, however, when I replied, “Five years,” the response was not an incredulous stare.

“Oh,” Jim Flexner said, “that’s not too long. I’ve been working on my Washington for nine years.”

I could have jumped up and kissed him, whiskers and all—

Even if you’ve mastered your digital urges, escaped the orbit of quick wins, and are seeking mastery in your very bones, my two cents—thanks to Caro—would be: Find a weirdo like you. Someone who normalizes you. You don’t need to have sorted yourself out. You need to surround yourself with weirdos like you.

👋Hi, I’m Satyajit. Welcome to my newsletter that picks apart the messiness of decision-making about business, careers, and life.

📚More reading…

Robert Caro’s The Power Broker

I missed reading this one before our chat! This post has a lot of context on that.

That aside, this one is the best bit for me:

Those who play the game of mastery use time to focus, to hone their craft, to perform a thousand repetitions, to seek simplicity in the most complex of things. Those who are after social approval and status see time as a needless decelerator that they must somehow hack.