#145 - Why AI may not leave us jobless

The concept of comparative advantage and the future of human work

If six in ten people at work are emotionally detached and a further two in ten are miserable, why do people continue to work? Given that the standard of living has improved so dramatically just in the last fifty years, why do they simply not quit their jobs and do things that bring them satisfaction?

René Girard, philosopher-polymath, explains the difference between need and desire in a 2018 interview:

Need is an appetite all animals have. We know very well that if we are alone in the Sahara Desert and we are thirsty, we don’t need a model to want to drink. It’s a need that we have to satisfy. But most of our desires in a civilised society are not like that.

I could, if I wanted to, check out of the economy, move to the hinterland, use part of my savings to buy a plot of land, build a house and a farm, and live self-sufficiently. Seems idyllic. I would have to probably set aside a non-trivial part of my life savings for medical expenses, but that aside, my expenses would be small. Perhaps I could make a long game of this. Live this way for the rest of my life.

Or maybe, a few spartan weekends up, I would miss dining out, miss having massages, miss ordering on Zepto, look at everyone on social media and stew…

I can peel this onion for as long as I want until I come to envy.

Our desires are not entirely ours. We model them on those around us. We mimic what we see. And then when we improve our lot, we level up our reference group. We work hard for that VP position, and then when we’re there, we happen to spend an evening at the twentieth class reunion. After that, we cannot sleep. We eye the SVP’s cabin.

Even though we need to be productive a lot fewer hours in the day and a lot fewer years in our lives in order to live comfortably, or at least as comfortably as our parents did, we keep redefining comfort. We keep chasing. Few get off this treadmill.

The world runs on envy. I’m a part of this world.

The more people look around the more they see models of desire and the more they are drawn toward them, like in a cult. Doctors are a cult unto themselves, so are bureaucrats and restaurateurs and VCs and other service professionals. Each group lives by its own set of rules. Members mirror each other’s behavior in an unending reflective cascade.

It is this same kind of social mirroring that is on show when the Gen Z’s take the afternoon off to tend to their cats or reject evening meeting invites because they have a life outside of work. The Gen X’ers may turn their noses up at the perceived entitlement, only because the ones on whom they model themselves do so. But if it catches on, then who’s to say they won’t want the same life?

The path of social contagion: consumption begets production

Dror Poleg, who writes about the future of work, explains:

…if you think about it, many of the services and products we consume would have seemed frivolous and unnecessary in 1900. We have dog walkers, sleep trainers, virtual girlfriends, diversity consultants, lactation consultants, and pet psychologists. There are many more professions to invent, and they will only be invented if more people experiment.

‘Frivolous and unnecessary’ because we didn’t have nearly as much leisure to indulge in. As the work day/week has shrunk through the last several decades, we have had more time handed back to us. In that time, relieved of the obligation to produce, we have consumed instead. Expanding consumption trends have led to more jobs and the need for people to do these jobs. A 2019 survey done by Lego revealed that more American kids want to be YouTubers than astronauts. All those vlogs consumed on YouTube have birthed a generation of aspiring YouTubers.

That explains why even though the average worker spends fewer hours at work each day, there are more jobs today than ever before.

And it is not just more jobs but better ones too. From hunter-gathering to agricultural to industrial to informational ages, the human lifestyle has become steadily privileged and serviced by technology. Farmland created farmers, industries created factory workers, automobiles created drivers. And within each nested professional loop, technology made the professionals better with time, always creating a better class of jobs with higher wages than before. Hence, the countering of the concern around large-scale human unemployment with the promise of 30X programmers.

So: just consume and new and better jobs will emerge. Professionals will be needed to do these jobs. The economy will live. End of story.

What if to answer the production needs of emerging consumption trends, it is not humans but AI that comes to the rescue? What if there’s a clear split between the roles of humans and machines where humans consume and machines produce? Wouldn’t humans who today get paid for doing the very same things be redundant tomorrow? After all, no previous generation had access to general-purpose AI that was as smart.

What if…

Imagine a world where human labor has been largely automated. What is left for us humans is a sliver of jobs that will draw the attention of increasingly competitive bidders. This will drive down wages. Too much supply, not enough demand. Leading to large-scale human obsolescence.

Far-fetched? What about the hand wringing of developers who, for the first time in a long time, are seeing their calls go unreturned by recruiters? Writes David Heinemeier Hansson of Ruby on Rails fame:

Seasoned veterans who used to have recruiters banging on their door nonstop can suddenly barely get a callback. And now the threat of AI suddenly got even more urgent and imminent with the launch of Devin.

Noah Smith, who runs the incisive Noahpinion blog on Substack and a self-confessed techno-optimist, stirs this germ of a fear:

… many people believe that this time really is different. They believe that AI is a general-purpose technology that can — with a little help from robotics — learn to do everything a human can possibly do, including programming better AI.

So, what is it going to be for the human race? Obsolescence or continued betterment?

Should Will lay bricks? Or maybe Virat should teach physical education?

In the 1997 Oscar-winning movie Good Will Hunting, Robin Williams’s Sean Maguireto, a psychiatrist, has this exchange with Matt Damon’s Will Hunting, a math genius who’s dragging his feet on an opportunity to work for the NSA, a US intelligence agency that Edward Snowden worked for:

Sean: It’s not about that job. I’m not saying you should work for the government. But you could do anything you want. And there are people who work their whole lives laying bricks so that their kids have a chance at the kind of opportunity you have. What do you want to do?

Will: I didn’t ask for this.

Sean: Nobody gets what they ask for, Will. That’s a cop-out.

Will: Why is it a cop-out? I don’t see anythin’ wrong with layin’ brick. That’s somebody’s home I’m building. Or fixin’ somebody’s car, somebody’s gonna get to work the next day ’cause of me. There’s honor in that.

Honor is impossible territory to settle this debate on because honor is table stakes. All forms of legalized labor being honorable, what is Robin Williams’s character trying to put across to Matt Damon’s character?

The concept of comparative advantage.

To understand it, let’s consider an athlete I’ve given up too much of my time for: Virat Kohli. For those for whom cricket belongs in the biology class, Kohli’s special skill is being able to predict the trajectory of a leather ball hurled at him at close to a 100mph and make contact with it with force and precision in front of thousands of people at the stadium. That apart, he’s exceptionally fit, in the top 0.1% of adults in the world. For someone whose millions depend on his physical fitness, it’s conceivable that Kohli could teach Physical Education at my daughter’s school. He would be more than adequate for the job. He may probably even be the best PE teacher in the city. Yet, that doesn’t mean he should switch to aerobics (clearly, I don’t know much about what they do at school in PE class).

Kohli has figured out that the talent for which he’s most valuable to the world is that of a cricketer. That’s his comparative advantage. What he gives up by being a professional cricketer—a PE teacher, a swimming coach (?), et cetera—pinches him the least. That’s his opportunity cost and his goal is to keep it at its smallest possible value.

At this point, if you’ve ever been parented, you would be familiar with the need for Kohli to become the best cricketer in the world. That’s a competitive advantage, a marker of how much better you are than the rest of the world at something.

Noah Smith explains the difference between comparative and competitive advantages:

Each worker ends up doing the thing they’re best at relative to the other things they could be doing, rather than the thing they’re best at relative to other people.

Even if Kohli were in the bottom 1% of all professional cricketers in the world, it would still make sense for him to make a living as a cricketer instead of as a PE teacher. Because that’s the best trade for his time. There’s nothing he can do with his time that would reward him as well. It doesn’t matter what the rest of the world is up to.

Matt Damon’s Will Hunting’s most valuable skill worth trading his time for is math. That’s his comparative advantage. That’s when his opportunity cost is zero—he’s making the most that he could make professionally. By spending his time solving equations and proving theorems (clearly, I don’t know much about math either), he’s leaving nothing on the proverbial table.

So, yes, while Will Hunting could be laying bricks in his Boston neighborhood or Kohli could be teaching PE at my daughter’s school, the opportunity cost for those career choices would be substantial. Because neither Will Hunting nor Virat Kohli would be playing to their respective comparative advantage.

The mental switch needed to hop off competitive advantage and hop on to comparative advantage is to stop thinking about the cost of production and think about opportunity cost instead. But it’s not easy to make this switch until we grasp the idea of constraints on production.

Why does your boss need you even though you’re worse than him?

Consider why my boss, Chief Strategy Officer of the firm, decides to spend a part of his resources budget on me even though he’s better than me at every single thing. Surely, my pleasant demeanor cannot compensate for the competitive advantage he has over me as a strategist. The reason is obvious, though not simple. My boss only has twenty-four hours in his day. He has a constraint on his time.

Time. That’s the throttle for human productivity.

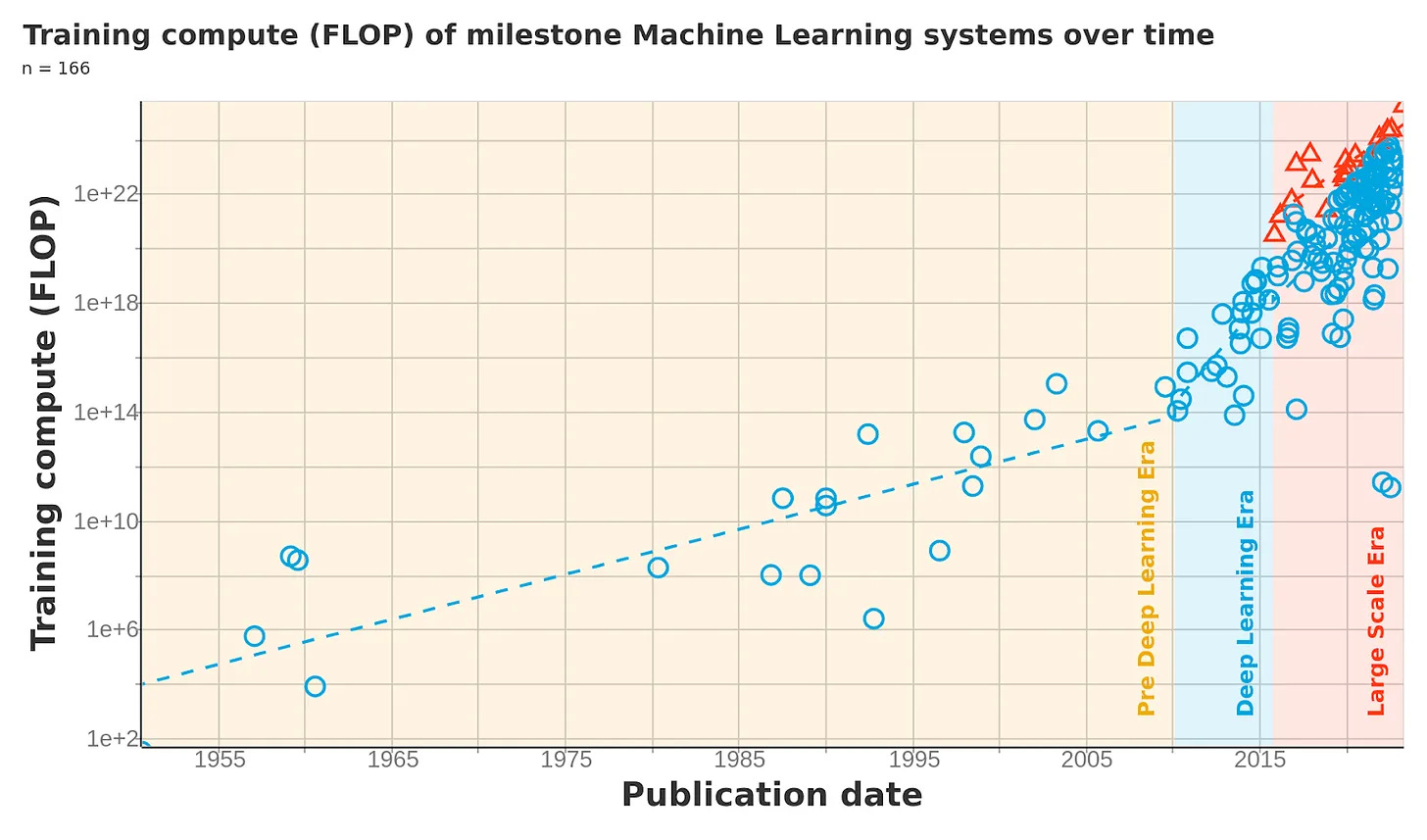

What’s the throttle for AI? What controls how much AI can be produced? It must cost something to train a model.

Some years ago, when I was leading a team that was building a smart writing assistant for scientists, I was unhappy with how long it took for users to receive an automated report detailing the quality of their manuscript. Here’s how a colleague explained the wait to me.

Imagine you’re off to the movies and you’re standing in line for a ticket. The queue goes all the way back and loops around twice. You don’t expect this movie to be a box office hit so you wonder what the fuss is about. You crane your neck and look ahead. There’s only one counter open that’s printing out tickets.

You can have the swiftest ticketer at this one counter but that wouldn’t make as much of a difference as having two more counters open in parallel. The simultaneous printing out of tickets at multiple counters is the best guarantee for speed. We can’t afford opening any more counters, said my friend stoically.

That is the principle dictating the speed of training AI models. More open counters, more hardware, more parallel processing. Noah Smith breaks it down:

AI requires some amount of compute each time you use it. Although the amount of compute is increasing every day, it’s simply true that at any given point in time, and over any given time interval, there is a finite amount of compute available in the world.

There’s a finite number of hours available to humans. There’s a finite amount of compute available for AI. Human power is to finite time what AI power is to finite compute. There’s the throttle. What happens when there’s a constraint? We realize we can’t do it all. We’re forced to prioritize. Will Hunting has to decide between mathematician and bricklayer. Virat Kohli has to pick between cricketer and PE teacher. AI has to choose between curing cancer and ironing clothes.

Well, not much of a choice, is it? Even if you consider the argument that AI will follow some sort of Moore’s law and become progressively cheaper.

As long as there’s a constraint on how much AI we can make (no matter how cheap tomorrow’s hardware is), AI will be deployed where it is most useful.

Here’s a scenario from Noah Smith.

Suppose using 1 gigaflop of compute for AI could produce $1000 worth of value by having AI be a doctor for a one-hour appointment. Compare that to a human, who can produce only $200 of value by doing a one-hour appointment. Obviously if you only compared these two numbers, you’d hire the AI instead of the human. But now suppose that same gigaflop of compute, could produce $2000 of value by having the AI be an electrical engineer instead. That $2000 is the opportunity cost of having the AI act as a doctor. So the net value of using the AI as a doctor for that one-hour appointment is actually negative [$1000 - $2000]. Meanwhile, the human doctor’s opportunity cost is much lower — anything else she did with her hour of time would be much less valuable.

We’re constantly matching a solution source with its lowest opportunity cost. For AI, in the above example, that match happens as an electrical engineer. That’s when it produces the maximum value, that’s its comparative advantage. The human, on the other hand, is at her best as a doctor.

Even when the AI has a competitive advantage over humans as both an electrical engineer and as a doctor, it gives up doctoring to humans because it’s not worth the AI’s time. It’s not a sacrifice because the trade-off is a net positive ($2000 - $1000). It makes sense for AI to keep spending compute on the highest-value-producing tasks.

We’re constantly generating more data. To use all of this data at the service of AI means meeting an accelerating need for faster and more robust hardware. Access to hardware (= compute) thus becomes a determining factor for the success of AI companies. Today, demand for compute beats supply by a factor of 10.

Imagine a time when AI is so powerful that it can be used for anything. But because compute for training AI is finite, AI will have a constraint that will dictate where it can be best deployed. At the same time, humans by consuming more and more will create new needs that will create demand for new jobs.

In such a situation, it wouldn’t matter how much better AI is than humans are at doing these jobs because AI will not have a comparative advantage at doing (most of) those jobs. As a result, humans will self-select and attempt to do these jobs in a way that is at a comparative advantage to them. In parallel, AI will lead to exponential economic growth and that will allow humans to be paid better than ever before (after inflation adjustment). This will go on, perhaps indefinitely.

Perhaps is not certainly. There’s a constraint on humans delivering value too. Humans use up resources. They consume energy too. In a tussle between humans and AI for scarce energy, who should be preferred? Where should energy be deployed—into generating more human power or AI power? And who will make this choice?

These are all questions for tomorrowtoday.

👋Hi, I’m Satyajit. Welcome to my newsletter that picks apart the messiness of decision-making about business, careers, and life.

🤿Rabbit holes for today:

Dror Poleg's article on production and consumption

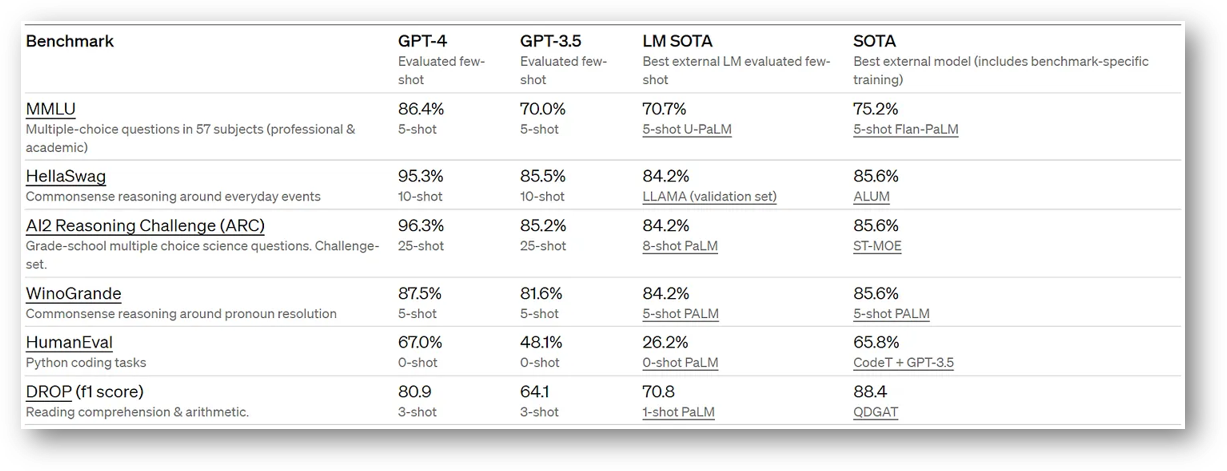

GPT-4 acing popular academic exams

Irony of being a developer today

How very Godelian. Since no system of rules can be both complete and consistent at the same time, the options are to either accept chaos or continuously add axioms to an ever-growing system of rules. Either way, there is opportunity. Either you create a productive pocket of order or you create new axioms. Probably both.