#139 - Why is hiring talent like buying a boring car?

Thinking about the problem of workforce homogeneity the Rory Sutherland way

‘The reason for this is that with one person we look for conformity, but with ten people we look for complementarity,’ writes marketing guru Rory Sutherland in Alchemy, his wonderful book on perceptual innovation.

A couple of years ago, my boss asked me to interview a candidate for an open position. She had good credentials, seemed smart, was from a top business school in the country, but she was just coming out of a two-year break from the workforce.

‘I’m not sure,’ I said to my boss. ‘I think we should keep looking.’

When hiring, we should understand that unconscious motivation and rational good sense overlap, but they do not completely coincide. A person engaged in recruitment may think they are trying to hire the best person for the job, but their subconscious motivation is subtly different.

Sutherland reads my thoughts with these words. I wanted to hire the best candidate but I was more worried about hiring someone who turned out bad. I did not want to take a punt on a less conventional candidate. The fear of bungling overrode my desire to do well.

This is not just my problem, by the way. It is a problem common to almost all who have to buy a house, a car, or hire talent unless — and we’ll get to the unless in a minute.

👋Hi, I’m Satyajit. Welcome to my newsletter that picks apart the messiness of decision-making about business, careers, and career design. I’ve recently put out to a playbook for middle managers to guide them through common yet tricky managerial situations.

House, car… people?

You probably think that an awful lot of problems in recruitment is the product of systemic prejudice that has been algorithm-ized, but once you get through today’s piece, I hope you’ll realize it’s more than that. It’s got more to do with the fact that the way we hire talent resembles so much the way we buy property.

To purchase a house, you will draw up a list of filters based on size, location, number of rooms, price; apply them in cumulation; and narrow the market down to five properties that remain in the overlap of your criteria; and then make your choice based on looks. This way you’re insuring yourself against bad finds. And so is everyone else who’s looking to buy a house. You’ve driven yourself straight to the most crowded open houses.

What explains your house-hunting process? Sutherland teases it out:

…when you have one house, it cannot be too weak in any dimension: it cannot be too small, too far from work, too noisy or too weird, so you’ll opt for a conventional house.

It’s not just houses, by the way. People buy cars the same way. In my decision-making community, as part of an exercise, I ask people to answer a bunch of questions about their choice of car to eke out what matters to them in the decision. All but one picked out all-rounder cars (safety, budget, mileage, looks). The only one who didn’t already owned a car. He was looking for a second car for the family. He was looking for, in Sutherland’s words, complementarity. The rest wanted the safety of conformity.

Going with safe choices for a house or a car — that’s understandable. We don’t want to get too funky with a long-term investment. But why should the same rules apply to hiring talent? After all, people join and leave organizations all the time.

Why is hiring like buying a boring car?

Because you think you’re looking for the best talent when actually you’re only willing to accept someone who won’t make you look bad. You’re terrified of a situation where you’ve hired one person who turns out sh*t.

💡Hiring people, much like buying a car, is about trade-offs. Some gains may be at hand, but they will come at a cost. The human mind has evolved to make such decisions. Here’s this bunch of juicy grapes hanging from a branch up top… Yum! but uh-oh… is it too high? What if I fall trying to get it? Will I break a limb?

You and me and all the readers of this newsletter and their friends and families have descended from, in Sutherland’s words, this slightly paranoid ancestor who let go of those juicy grapes because she feared dying more than she wanted those damn grapes.

Back to my hiring decision. What was steering my decision was this unsaid rule:

👉Less good on average but has lower variance seems a better trade-off than better on average but has higher variance.

❓The candidate I was considering had been a career achiever. But the two-year break on the CV was the source of her variance.

❓The car you’re considering has got the torque under the hood. But the new brand makes you wonder if the service network will be wide enough.

❓The house you’re considering has got a beautiful balcony overlooking a stretch of mangroves. But the proximity makes you wary of mosquitoes and malaria and dengue.

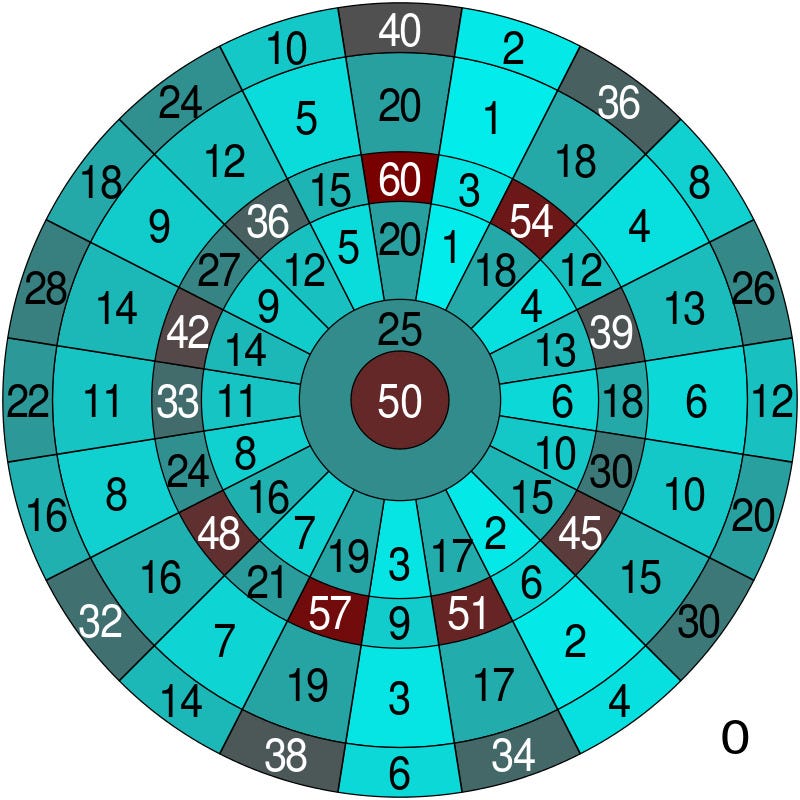

In a six-year-old talk titled My Advertising Is So Efficient It No Longer Works that I only just discovered, Sutherland explains, with a brilliant analogy, the concept of messy trade-offs humans have always learned to make. He compares human decision-making to playing darts. While archery is all about maximization—the closer you get to the bullseye, the higher you score—a dart board is set up differently. It forces you to consider not just the potential gains but also the possible risks.

You may try for the 3X ring straight up top and aim for a 60 but land a tiny bit to the right and you end up with a 3! You may do the math and say that between 60 and 3, the average comes to 31.5 — a perfectly good score. But if you have just one chance, would you take the risk? Would you be okay with a free fall to next to nothing (3) in going for glory (60)?

Now that you’ve got the point, let me take you back to what tends to happen in organizations.

The most common hiring situation in organizations is individuals hiring individuals.

In my Middle Manager Playbook, one of the described situations has Yamini, the manager, delegating hiring to a few of her reports. She thinks this will allow her to pick up the pace of recruitment for her growing team. But the opposite happens. Tasked with hiring, her reports don’t want to goof up. So each of them looks for a median candidate, someone who can be justified as a good hire by all acceptable standards. They get very picky. This slows things down to a crawl. HR is pissed. The situation escalates until Yamini has to intervene.

Now imagine if Yamini’s reports had succeeded in their pursuit. Would that have been a good thing? For one, I suspect their efforts to conform would have brought in too much sameness, as they looked for candidates with acceptable attributes on every parameter. Without aiming for it, the team (and firm) would have ended up with a group of fungible hires. A fleet of boring cars, if you may. (In pre-liberalized India, that probably was the humble Maruti 800.)

What if we hired talent the way coaches draft sports teams?

How do we get out of this morass of conformity? The thing is that this conformity worked just fine before the knowledge economy. Factories had no reason to encourage innovation and the variance that came along with it. They operated on consistency. As the workforce has expanded to white collar, the demand for creative talent has gone up. The human brain works the same way, though. It still hates uncertainty. And creativity, almost by definition, means a higher threshold for uncertainty.

In his book Leading, Alex Ferguson, perhaps the most celebrated manager in football history, talks about the value of maintaining balance in the squads he coached. Balance is nothing but complementarity. Ferguson made it a point to mix young blood with experience, aggression with caution, the wild cards with the dependable. He did not look for this balance in every individual, but in every team that he managed.

💡The smallest unit of complementarity is the group, not the individual.

Unfortunately, in organizations, we look for a bit of everything in everyone. How do we get past this tendency?

Sutherland sheds light on this in the same talk:

…if you're making one decision you go very very close to the expected boring norm. There’s a solution to that. If you hire people in groups, without any bidding whatsoever people will automatically make diverse hiring decisions because now they’re looking for complementary skills. They do this instinctively.

Hiring in batches seems to shift the focus from being right with every hire to being right with every group that you hire for. The group or team as a whole is covered on all important bases but the individuals are each allowed to be a little less stereotype, a little more like themselves.

Ogilvy recruits creative talent through a scheme called ‘The Pipe’ where ‘applicants don’t have to be graduates; they don’t have to be young; they don’t have to have any qualifications at all.’ I don’t know how much of a success the program is or how well it can travel outside advertising and marketing. The point though is that even the best rules are only rules of thumb. Only contextually effective. More from Sutherland on the problem with our well-intentioned efforts to be fair:

…you can create a society which maintains the illusion of complete and non-random fairness, yet where opportunities are open to only a few — the problem is that when ‘the rules are the same for everyone’ the same boring bastards win every time.

Bring in hiring algorithms and you have put this problem on steroids. Hiring algorithms are made to help hiring managers spend less time on resumes that don’t match job requirements. When these algorithms apply hard rules to all situations, they split reality into black and white. The outcome is always stripped of vital information and seldom reflective of reality.

Hiring algorithms are not programmed to be prejudiced. That’s the irony. 😵

My boss saw my well-meaning effort to avoid a regrettable hire for what it was. He overruled my recommendation and went ahead with the hire. By his actions, he suggested to me the big picture, his vision for complementary skill sets in the team he led. I’m glad he did that because that hire whom I have managed since has turned out to be a source of pride and a pleasure to work with. I couldn’t be happier to have been wrong.

Have you had an experience that speaks to today’s topic? Or maybe you have seen hiring in practice that works around our (somewhat extreme) human tendency to avoid regret? Share your take in the comments.

📢Do try the Middle Manager Playbook and, if you find it useful, share it with friends. Your support will encourage me to do more 🙏

Until next week…

Superb piece! The insights presented here bring out such a meaningful relation to our collective experience. At the same time, they're tangible and actionable. Also, very interested in reading more of Sutherland's work now!

Thank you for giving me some more precise and insightful language around the decisions we make and the decisions made for us!

Absolutely love the depth, nuance, research and clarity that goes into these issues,

I know I am lagging and have around 100+ issues to read,

But incredibly pleased with all the issues I have read so far.

Thank you Satyajit for Curiosity>Certainty 🤝🏻