#131 - Let Me Tell You about That Most Misunderstood Concept

You will never look at complacency and performance improvement programs the same way again

I’ve a few Kahneman stories filed away in my head. My second favorite (after the one in which he responds to a reporter’s call asking for a byte on his friend and new Nobel laureate Richard Thaler by saying, ‘Thaler’s most special quality is that he’s lazy.’) is one where, as his contribution to an online magazine’s collection of scientists’ famous equations, he offers:

success = talent + luck

great success = a little more talent + a lot of luck

Oh, how I love this self-deprecating chap!

This equation, in my humble opinion, is an onion. And in today’s issue, I will peel it for you.

Regression to the mean is a mouthful of jargon. What it means is prosaic.

Most outcomes in life are a combination of skill and chance. The more the element of chance, the more random the outcome is. The more the influence of random factors, the greater the swing from extreme outcomes to moderate ones.

Indulge me in this thought experiment. You know that a coin toss is random. But imagine it took a certain amount of skill to get heads on a coin toss. The game is to get as many heads as possible in ten coin tosses. A beginner coin tosser will maybe score two heads out of a set of ten. An expert will get eight or more. Now, say, you get three heads from your first set. It would be reasonable to conclude that your chances of getting to eight in your next set are very slim. Because the gap in skill needed for a three and an eight is too big for anyone to bridge in one try. You’ll probably need to train several months at the National Coin Toss Academy and practice under regular supervision before you can make a go at eight.

Now hit pause on your fanciful thoughts. Slowly return to reality.

Now play the same game with the same rules, with just one change. The coin toss requires no skill. It is entirely random. So you go. In your first set of ten, you toss two heads. In your next set, you get to — voila! – an eight. You’re happy but you somehow are not entirely gobsmacked. Assuming you find this outcome believable, allow me to ask you why you find it so.

For a simple reason — the outcome is pure chance. Over a small enough sample, which is what ten coin tosses is, it is very much possible for you (or anyone) to score eight heads. You get giddy at this early success. You wonder if you can be a professional coin-tosser. You go all in, trying to make it big in this exotic profession. You practice tossing sets of ten over and over again, every day. A few months pass. The results should be there for you to see. Going over your scores, you find sequences of eleven heads and thirteen tails, but your overall average is split 50-50 between heads and tails.

The only thing it means is this:

If you try to measure some attribute on N occasions (where N is a large number), and that attribute is governed by random forces, then the overall measurement will tend to stay close to an average value.

I asked ChatGPT to come up with headlines from different walks that laugh at the idea of regression to the mean. These are what it gave me:

📢Politics: New Mayor’s First Month Sees Record Low Crime Rates: Promises to Eliminate Crime Entirely by Year's End

📢Sports: Rookie Hits 5 Home Runs in Debut Game: Fans Expect Season Total to Surpass 800

I prefer a cricket version: Rookie Hits Fastest Century in IPL History; Experts Hail the New AB de Villiers

📢Cinema: Director's Multi-Starrer Film Is a Dud at the Box Office; Studio Backs Out of Next Venture

Now do you see it? But let’s face it — you’re not in the movies or in politics and coin tosses are not a big deal. What are some situations when the hand of lady luck is not acknowledged in your line of work — that is, in knowledge work?

What do you not see when starting a company or launching a product or hiring a candidate?

What makes such decisions especially tricky is not just the role of luck is under-emphasized in general but also that you almost never have access to a big enough sample size, so you end up judging on a small and unrepresentative data set. You judge a second-time founder over their last venture, a product manager over their last couple of products, and so on.

What to base my judgment on, you ask.

On the strength of the correlation between skill and the outcome. How closely related are skill and the desired outcome.

All outcomes are random in different proportions. You’ve got to form an idea about the degree of randomness. That’s the work. If the correlation is perfect, it means they move together. If it is imperfect, they travel apart (depending on the degree of imperfection).

This approach moderates your prediction by taking the evidence and regressing it to the mean based on the strength of the correlation.

👉If there’s a strong correlation between the outcome and skill, the adjustment is small. In other words, the outcome is skill-dominated. Roger Federer at Wimbledon?

👉If the correlation is weak, the adjustment will be big. You will not read too much into the fact that the social media manager CV on your table has three successful campaigns, all centered around the same influencer who went viral just before the campaigns and had a follower base that very closely matched her previous employer’s target audience. Take out those situational factors and the outcome is hard to replicate.

Let’s go back to Kahneman’s favorite equation:

success = talent + luck

great success = a little more talent + a lot of luck

What Kahneman seems to be saying is that, by and large, luck has a big hand to play in unprecedented success. But the reason he seems to suggest it as an non-obvious insight (and not an obvious truth) is because people love attributing success to something within their control. Imagine a parent or teacher tasked with explaining this equation to a teen who prefers smoking pot to anything remotely constructive.

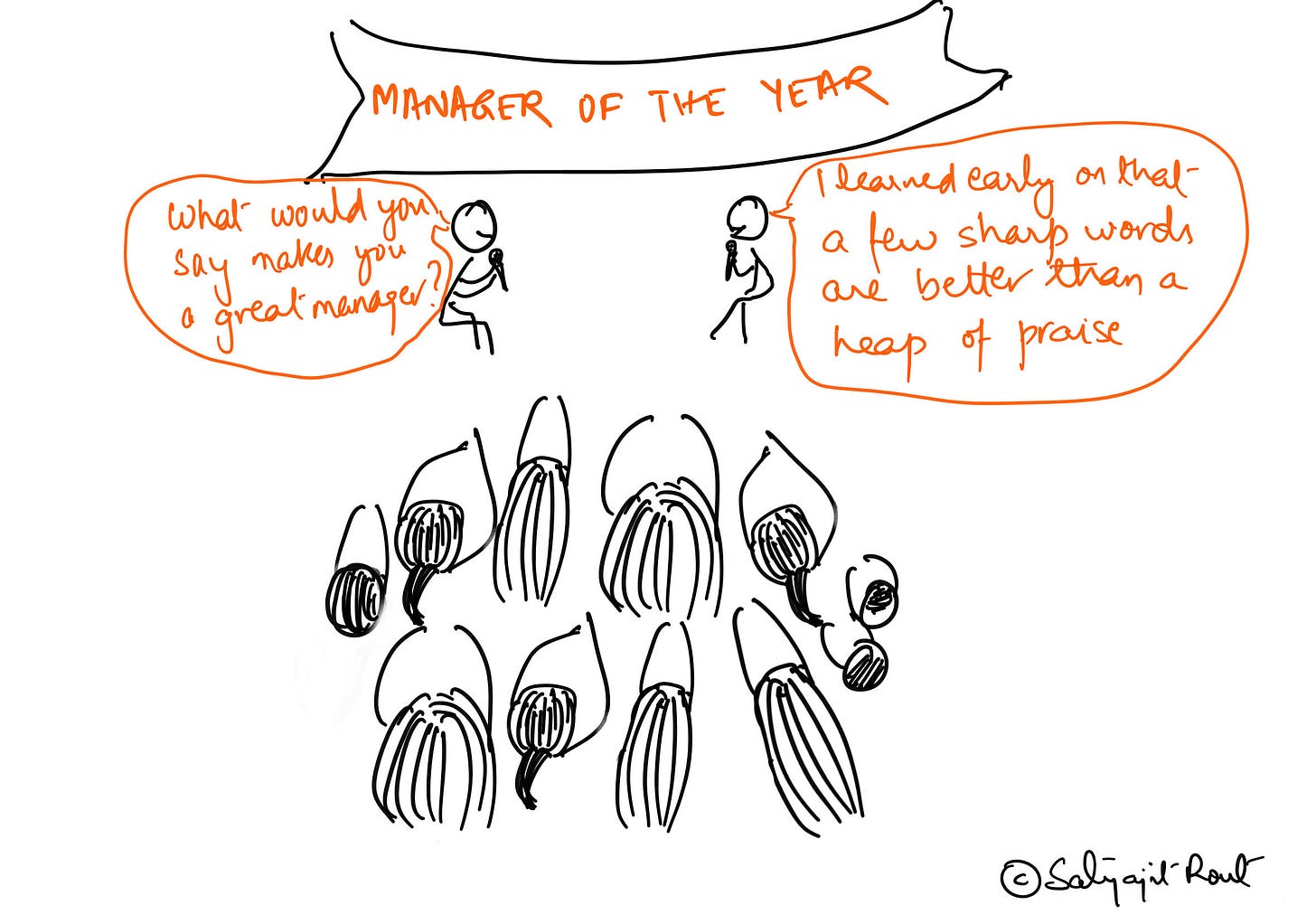

Just as parents choose to believe it was their tough love that helped pull their teen from the doldrums, marketing managers do not want to change a thing from the last campaign if it was successful and founders are worried about their second line getting complacent after a blockbuster year.

All are explained by regression to the mean. Few are acknowledged.

Additional reading

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Superforecasting

Thank you for reading. In the midweek issue, I’ll use Kahneman’s equation — remember the thing about it being an onion? — to show you how the very best manage to get the better of regression to the mean.

Lucky Human Beings will forever try to find magic in the method, method in the magic, and try to engineer creativity, and sometimes creatively engineer solutions,

Whether they succeed in the quest is sometimes secondary, sometimes the quest itself is autotelic and transformative.