#124 - How to Avoid Being a Rich and Wretched Founder

The Netflix approach to building an innovation culture (Part 2 of 2 on rethinking rules)

In Part 1, we discussed why we like freedom for ourselves (so, no rules) and control over others (so, more rules). We are overconfident of our own ability to do things that move us closer to our big goals in life while we’re underconfident about the ability of others to perform without controls. So, we tend to govern the output of organizations by laying down rules.

In this week’s edition, I will make a counterintuitive case: fewer rules are better for creative companies. And wrap it all up by sharing with you, dear reader, the story of a famous entrepreneur who has tried his hand at more rules and no rules. And there’s a framework somewhere in there as well. One that may just hand you a vocabulary to identify the kind of firm you are in and what it may mean for you. I will call this one the Talent-Transparency Framework.

This week’s highlights:

Historically, business owners have extracted productive work by imposing controls over worker behavior. Such a management system was predicated on the assumption that consistency in output was non-negotiable.

Business models in the internet era have a shorter shelf life than ever before. A workforce good at following rules and chasing incremental efficiency has limited impact during technology-enabled leaps in the market.

In such an exponential age, to be an innovative company one needs flexible thinkers who can rip up the old book of rules and build things from scratch. Such talent needs a culture of transparency freed from the weight of process and command-and-control decision-making. That is the other ingredient in Netflix’s recipe for success.

The last step is giving freedom to such a workforce in such a culture so that they reciprocate by acting responsibly in the best interests of the business. This is the hardest to pull off at scale.

This interplay between talent and transparency levels in organizations shows itself in a variety of ways, captured in the Talent-Transparency Framework. A company that falls in the optimal quadrant in the talent-transparency matrix is Reed Hastings’ Netflix.

Rich and wretched

Reed Hastings had just nudged past 30 when he started his first company Pure Software in 1991.

Pure’s main product was a piece of software that helped programmers debug code. Getting this part right, I guess, was easy for Hastings, a programmer by trade. It was when he had to don the suit of an executive and run a company that in one stretch of 18 months acquired three other companies that he found himself in a bog.

He wasn’t cut out for it. His response ‘every time we had a significant error – sales call didn’t go well, bug in the code’ was to set up a new rule, a new process that made sure that the mistake didn’t happen again. The result? Pure became more bureaucratic, less innovative. Hastings was bummed as the CEO and founder even though he was steering a highly successful enterprise.

(If you’re curious how so, then let me tell you that it’s all in the timing baby. Pure was greeted by a receptive market. A great market trumps all other contributors to startup success.)

Pure Software was sold to its biggest competitor in 1997. Pure’s first round of funding was by friends and family for all of twenty grand. In six years, Hastings had made $750 million (well, not all of it) off it. That gave him the seed money to launch Netflix the same year.

Despite the riches, Hastings had misgivings. He didn’t want to go down the dummy-proofing route of running growth companies. He had a hunch that Pure’s culture didn’t scale too well because it was peopled by those who aggressively toed the line. And the firm in turn was a lightning rod for the more compliant because management believed in rules—the more the merrier.

A young and successful entrepreneur, fresh off of a multi-million dollar exit, is gloomy about how he ran his venture. Oh, the headline!

I’m not sharing Hastings’ story to drive home the irony. It is to point out our tendency to default to rules and processes when managing uncertainty. And nothing encapsulates uncertainty better than managing a firm for success in the modern exponential age where technology redefines the game every few years. In this uncertainty, we need to nurture the firm as a living organism and trigger creative mutations in it so that it can adapt to a rapidly changing environment.

But why should this mean we should not have rules? We probably need them even more. Here’s me making a case for rules.

Why having no rules should fail miserably

Here are five of my best reasons why No Rules is a doomed strategy.

For almost all of human history, the right strategy has been to improve what we’ve got by setting rules. And then only some of the time, we’ve had to change—the old rules didn’t apply. Horses to automobiles to electric vehicles. Why chuck something that’s worked through history?

In professions where failure means disaster (soldiers, doctors, cops), people work better with rules than without. Rules are the forcing function. They preempt the worst outcomes. No patient would want doctors to perform surgeries any which way they feel right.

Without rules, people won’t agree to working common hours in a day, common days in a week, and so on. Days before a product launch, your backend engineer will hop on a cruise. Your design head will buy himself and his team high-end gaming monitors for work. And so on.

Given the freedom, people will make decisions as they wish. As the boss, you will be alarmed to find a new product greenlit or a key campaign stopped abruptly because someone thought it fit.

People will say whatever they feel is right anywhere, anytime. This will spawn a culture where feedback on performance and of person become one and the same. Employee morale will sink.

A fear of no rules stems from the notion that workers will fill the rules-shaped hole any which way they feel right. That makes sense. We warn our kids with this all the time—you can’t just do whatever you want!

What the heck was Hastings thinking?

Just as you are right now, Hastings took these concerns seriously. But he didn’t stop at that. As Netflix grew and faced new challenges, he committed himself to exploring a new model of work that could help him run Netflix sustainably without having to take charge of his employees’ lives little by little by laying down more rules every time something went wrong.

I said explored so you should not expect a rosy narrative. Running a different workplace meant dealing with problems that would be stopped at the door at any regular workplace: employees stunned by critical feedback, managers stunned by hotel bills worth an arm and a leg, a boss who took a full six weeks off in the year.

💡But Netflix persisted with, practiced, and perfected a culture of no rules for two decades since going public. In that time, its stock price has snowballed from $1 to $410. For context, $1 invested in the S&P 500 would have come to between $3.5 and $4 today.

Here’s my version of what Hastings’ Netflix found from its explorations into a knowledge organization without rules. They are gleaned from Hastings and Erin Meyer’s account of Netflix’s journey to no rules.

Horses - 5000 years, fossil-fuel-powered cars - 100 years, electric vehicles - ? The shelf life for gold standard technology has continued to shrink through history. Innovation means the game will keep changing faster, and the leaps we had to make only some of the time will become more frequent.

Most work is not high-stakes work. Most knowledge work is coming up with a better mousetrap. Innovation needs freedom to try out variations without fear of being judged harshly.

Knowledge work is outcome-dependent, not output-dependent like factory work was. Set expectations around how to use freedom responsibly. Actually treat your employees as functioning adults who can see complex things like what is the common good and what will be detrimental to others.

The command-and-control system of yesterday lacks the agility and diversity in perspective that knowledge work demands today. You need to hire and train flexible problem-solvers who can change with the times.

The best way to turn talented performers into outstanding ones is by letting them give each other candid feedback frequently. The fear of spawning ‘brilliant jerks’ is neutered by giving people freedom to speak their mind and coaching them to use it effectively.

To build on these points, and before we get to how Netflix built a culture of no rules, I want to present to you the Talent-Transparency Framework.

An alliterative framework

Adam Grant believes ‘it’s a lot easier to shape culture through who you let in the door than through trying to radically change people’s behaviors.’ Talent matters in knowledge work. Talent separates the exponential from the incremental. Pardon me but this is a cliche. We all know this.

What we know much less is how to treat talent. What do we do with it? Handle it with kid gloves? Keep it on a tight leash? The second ingredient, call it the secret sauce even, is transparency.

It’s not exactly a secret, is it? Your own firm’s culture book probably has the word in boldface a few times but you know better than to fall for it. You probably get, as a pragmatist, that diplomacy works better than bluntness in the corporate world. Yet, bigwigs like the Collison brothers at Stripe and hedge-fund guru Ray Dalio from Bridgewater swear by radical transparency. What are they smoking?

The answer, I believe, is captured in a framework called the Talent-Transparency Framework. It captures four broad ways in which organizations mix talent and transparency and what comes out of them.

👉Conflict avoidance, hierarchical decision-making, and information asymmetry are signs of a healthy Bureaucracy. Employees would get feedback once a year and would be upset and surprised by the contents of it. Or the CEO may have to approve of laptop purchases. And one may hear ‘well, this is beyond my paycheck’ in the cafeteria. Or those on the frontline may be left wondering about the whys—Why the most recent org restructure? Why has a product line been sunset, and another continued with? In six years, Hastings’ first venture Pure Software had become a slow-acting, inflexible Bureaucracy. 😨

👉Across two decades, Hastings’ second venture Netflix has evolved into Exponential Innovation. Similarly, Stripe makes publicly available the ‘vast majority of Stripe email (excluding particularly sensitive classes of email or threads where a participant has a strong expectation of privacy).’ Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater video-records all meetings for future reference and learning. These are cultural artifacts unique to the top-right quadrant.

👉My hunch is that startups tend to start out as fast and flexible. And then, as they grow, they accumulate layers of management and of controls. Depending on the demands of the market they’re in, they may have to grow too fast and compromise on the talent while trying to remain open. This may edge them toward Slow But Steady Innovation.

👉Or firms may continue to attract top-draw talent as they grow but these poor guys have to do two jobs at once to move up the corporate ladder. One would be the job they’ve been hired for and two would be to talk about the job they’ve done. Such is life in Optics and Politics land.

How can your firm aspire to be in the top right quadrant of the framework?

Netflix’s 3-step process

We can learn from how Netflix did it. It’s simple:

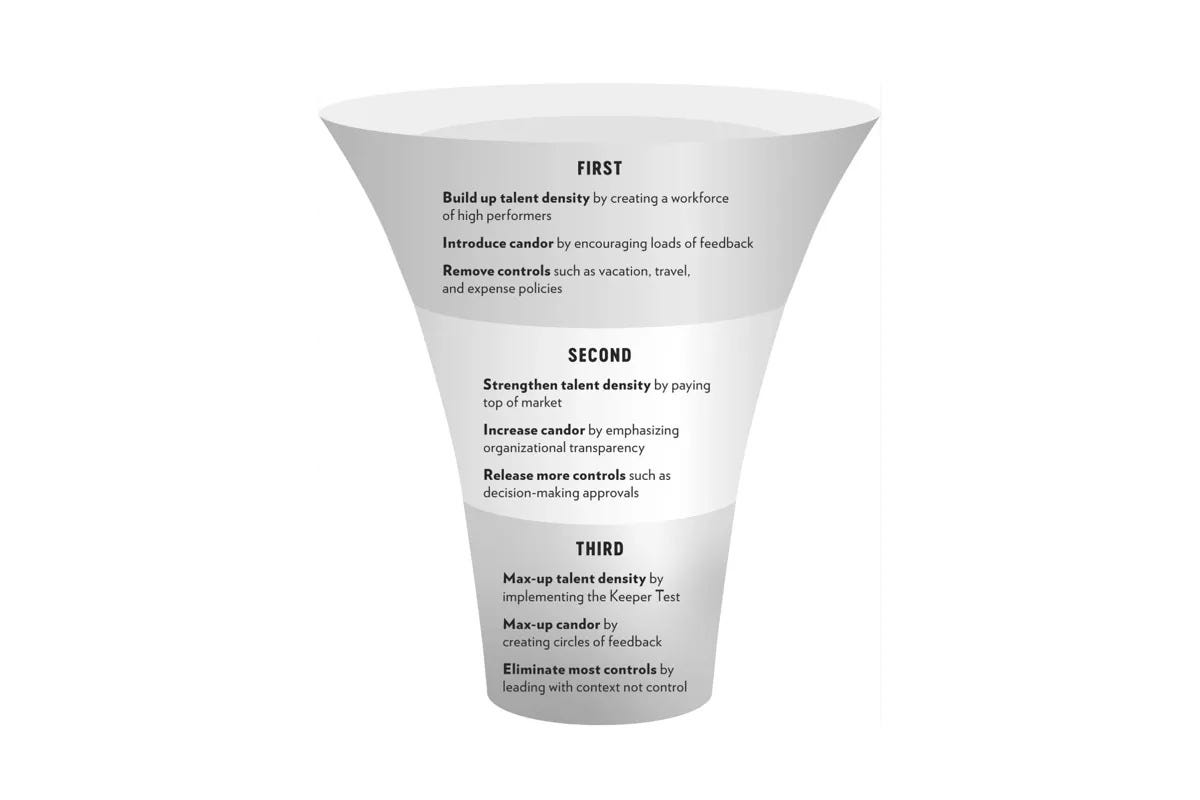

1️⃣Build up talent density (hire ‘wildly competent’ performers, fire just competent ones)

2️⃣Cultivate candor (transparency, feedback, open books)

3️⃣Remove controls (rules, policies, processes)

Read them again and you may appreciate the simplicity of the message: An innovative organization has two parts to it—people and culture. Just two parts! But to get these two parts to work in sync, you need an enabler. And that enabler delivers value by subtraction, not addition, of rules.

It’s not so simple after all. Because the way people and culture mix in most organizations veers them away from the Exponential Innovation quadrant in the Talent-Transparency Framework. Here’s a sample I gathered for you:

Will Larson is CTO at Carta and has been a software engineering leader at Calm, Stripe, and Uber. Sample this experience of his at Yahoo.

When I left Yahoo, my Director asked me to explain my decision, and I ranted at him that I was disappointed by the lack of effort within my team. Several of my colleagues accomplished so little in a year that I was able to reimplement their work, running faster and using significantly less memory, in a weekend. This wasn’t because I was experienced or exceptional–I would generally say that I was neither–simply because I maintained a fairly moderate level of effort. This was, from my point of view, a major failing. My Director disagreed. Instead, he argued, you need all types of people in an organization. You need folks who push hard, but also those who are willing to maintain the boring pieces at a slow pace. Rather than a failed organization, this was good governance.

You need all kinds of talent. Where else have we heard this? This kind of talent management philosophy is codified in business books. No wonder Larson’s Director at Yahoo was so sure of himself—and for good reason too because you cannot afford high performers without a culture that suits that level of talent.

So how did Netflix do it?

The answer is plain. In the book No Rules Rules, co-author Erin Meyer recommends taking ‘a little step toward talent density, a little step toward candor, and then a little step for freedom. And then you do it again. And then you do it again. And then you do it again.’

What Meyer and Hastings seem to be saying is that it takes getting used to for both bosses and employees. It is not natural to open up strategic decision-making. It is not natural to shout out criticisms at your boss from the back of a filled-out room. It is not natural to treat employees as fully formed adults. You’ll have to fight your instincts at various points. But here’s a blueprint. Now, go figure.

Coda

Traditionally, organizational culture has been built on the premise that rules and processes are the only way to productive human cooperation. This essay, drawing from the Netflix story, challenges the belief. It then argues that freedom to the individual worker is more important today than ever before because of the demands of a rapidly evolving world. We need to trigger mutations, not suppress them. We need to do that which brings us agility and flexibility, not stability and consistency.

Of course, if you’re not a part of this exponential world that is run by technology and creative work or you’re in a profession where human lives are at stake, then perhaps rules and process are your bedrock. Build on them. But if you are, like me, part of a knowledge economy that thrives on flexibility, speed, and innovation, this is for you.