#107 - Chasing Greatness: Shoot for the Moon but Only If You Can Train the Monkey First (Part 2 of 2)

Hello friends👋

Henry VIII ruled over England with an iron fist for thirty-six years. For much of the second half of his reign, his foul mood concerned Parliament. Word went that Henry VIII’s famed temper was down to leg ulcers. Painful and untreatable, they irked the King of England to tyranny. A sour Henry coped by eating and drinking. Being a monarch, he probably had the pick of the spoils. But poor Henry’s ulcered leg didn’t let him burn those calories off. He ballooned. It probably didn’t help his state of mind that for a while he didn’t have a male heir to the throne and he kept going through wives to help him produce one.

Pic: Iconic portrait of Henry VIII from 1536 by Hans Holbein the Younger. Labeled a work of propaganda by some for the brushing over of the leg injuries incurred by Henry earlier in the year.

Now imagine if Henry could walk into a clinic as you and I do today and get his leg ulcers fixed for good with laser surgery. Or the Royal GP could prescribe him a course of antibiotics for his infections. The marvels of modern medicine that we don’t even think about for a moment today were in the 1500s ones people could not imagine even if they tried to.

What were the stepping stones between leg ulcers and antibiotics? Could we have predicted the greatest advances that got us from Henry VIII to Alexander Fleming? Could we have set them as ambitious objectives and made a plan to accomplish them?

In the first half of this essay, I offered a no, chiming in on the insightfully written Why Greatness Cannot be Planned by AI researchers Kenneth Stanley and Joel Lehman. For the simple reason that the future is recombinant. The ingredients for it are still in the making. We don’t know what we’ll need, much less for what.

Yet, it is also true that freethinking ambition needs patrons and deep pockets. Even science, the purest search for knowledge, cannot be unlocked without grant proposals to funders on which scientists burn months justifying line items for expense.

Progress needs measurement. Ideas need objectives. Gatekeepers need assurance. And even if somehow such wrinkles were to be smoothed out—maybe we had a Medici family as our sympathizers—there’s a snag in the fabric that’s hard to ignore. It is that we are socially conditioned to be uncomfortable without a yardstick for measurement. We are so used to judging and being judged for our efforts that an open-ended search is disorienting, even pointless, to many of us.

So how do we pursue greatness if we don’t know and can’t see the exact path to it? What do we do with never-done-before ideas? What is another way to develop world-changing ideas if we can’t plan them as projects on the calendar?

Here are the highlights from this week’s piece:

Even the best lack the good sense to quit when the time is right. So, they define the breakthrough point in advance and make a precommitment to quit if you fall short.

The breakthrough point is both a state and a time. You don’t have unlimited time and you cannot compromise on the state.

Chasing greatness is not a once-in-lifetime chance. It is a repeating option and it demands that you’re ready to walk away if you get stuck.

A moonshot factory stands to be reduced to ashes after every failed project. But the ashes are nothing but moonshot compost from which sprout new ideas.

Uncertainty is a constant companion of those with deep ambition. The worst thing to do while chasing greatness is to pretend to be more sure than you are.

The case for X

X, Alphabet’s innovation lab and Google’s sister company, is called a moonshot factory. Teams at X are paid to pursue designed-to-fail ideas (like turn seawater into fuel) in their search for radical impact. They are also expected to be willing to give up the pursuit if—and they decide the if early on—they fall short of the breakthrough point.

The breakthrough point is both a state and a time, and falling short implies that what you’re building is not in state A by time B, where both A and B are pre-defined. Before the start of any moonshot project, the project leader makes a precommitment to quit if the team falls short of the breakthrough point.

In Astro Teller, X’ers are led by someone whose responsibility as Captain of Moonshots is to make the world a better place. Teller outlines what they do at X in this pithy quote:

You can’t pre-business-plan a moonshot any more than you can paint a masterpiece by color-by-numbers given to you by committee.

This kind of roomy yet uncomfortable scale could lead to chaos. Only, as the portfolio for X bears out, it is our most proven vehicle for a method that nurtures creative madness.

Let’s pick apart the machinery that powers the world’s most riveting moonshots.

Train the monkey or shut shop

A few weeks ago in this newsletter I published this passage as part of a piece on the value of solving the hardest thing first when on world-changing pursuits:

‘Let’s say you’re trying to teach a monkey how to recite Shakespeare while on a pedestal,’ says Astro Teller who heads X, Alphabet’s moonshot factory. ‘How should you allocate your time and money between training the monkey and building the pedestal?’

‘The right answer,’ Teller continues, ‘of course, is to spend zero time thinking about the pedestal. But I bet at least a couple of people will rush off and start building a really great pedestal first. Why? Because at some point the boss is going to pop by and ask for a status update — and you want to be able to show off something other than a long list of reasons why teaching a monkey to talk is really, really hard.’

Pic credit: Moonshot mindset @ X

In Teller’s memorable metaphor, the monkey is the bottleneck and training it is the breakthrough for the project. An ambitious venture will present multiple challenges but one above all else has the power to make or break the project. Find it, solve it, power on. Or quit.

What sort of a claim to greatness is quitting? What can you achieve by giving up?

Seems like a lot. In over twelve years of operation, X has been an incubator of hundreds of moonshots, a number of which like Waymo (self-driving cars), Verily (ML-powered disease management), and Mineral (climate-resilient food system) have graduated to independent businesses.

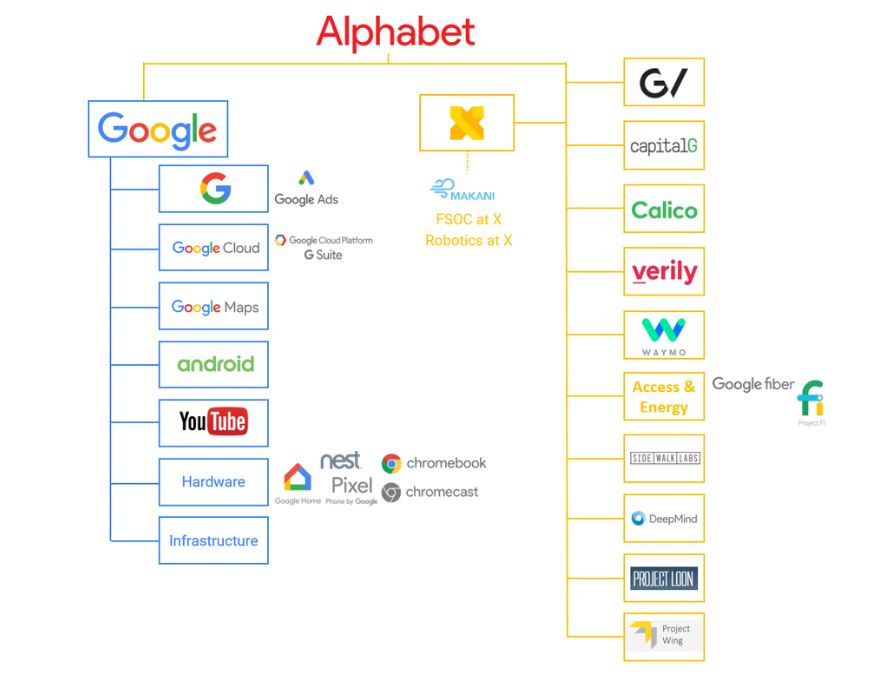

Pic: What makes Alphabet

A three-step recipe to quit something you dearly love (and do something great)

Undergirding the monkeys-and-pedestals thinking is the belief that the pursuit of greatness is a repeating option. That you will have more crazy ideas to go for than you have time, money, or energy to throw at. By giving up something that is undoable, at least in the prevailing state of the world, you free yourself up to pursue something else as big, or bigger. This is the opportunity-cost mindset that the moonshot takers at X have cultivated.

One gets an understanding of how X’ers do this by studying the X ways of working. Among the tenets, there are three that stand out for the purpose of our discussion. Of these we already know the first one:

1️⃣ Tackle the monkey first.

Figuring out how to tackle the monkey will not come as a step-by-step plan. Here are two more tenets to help manage the process of pursuing far-out ideas.

2️⃣ Focus on the outcome, not the output.

Anyone who prides themselves on their problem-solving knows that it can be hard to give up a problem they’ve put their heart and soul into. But just because something is hard to do doesn’t mean it is worth doing. There’s no point in turning seawater into fuel if it cannot be done at a cost that makes it a viable alternative to fossil fuels.

X’ers stay the course by being passionately dispassionate. They keep their skepticism close and ‘learn to look dispassionately at the results, so we’re ready to change course or walk away when that is the right thing to do.’

But how easy is it to be passionately dispassionate when sunk costs accrue, commitment escalates, and the siren song of a just-round-the-corner breakthrough rings loud. This is where their relationship with failure comes to the fore. The third and final ingredient in the recipe shines light on this.

3️⃣ Embrace failure learning.

Eugénie Rives, leader of Project Move, a robotics moonshot, says:

We were developing robotics and AI solutions for the logistics industry and the next day I would have to tell my team that we were shutting down the project. We were weeks away from unveiling ourselves to the public and deploying to our first customers. But that afternoon, I’d made the incredibly difficult decision with X leaders to kill our moonshot.

Weeks away from deployment of a multi-year project, Rives decided that the monkey was intractable. She continues:

The process of winding down my own project was the most painful in my career, yet, I’ve never learned so much. It made me realize how important it is to have intellectual honesty when you’re working towards bigger goals. It made me a stronger and more resilient leader. And it helped me understand just how fertile the ashes of killed projects can be.

Moonshot Composting - the shared soil in the path to greatness

Moonshot Composting is something you probably haven’t heard about.

Nonetheless, the idea behind it would be deeply familiar. We all have failed and used the remains of the experience to make something useful later in life. How do we do that when the stakes are high?

That is exactly what is going to happen in a small village in Tamil Nadu in the coming months. The unsuspecting villagers--those least able to pay--are going to receive high-speed Internet. All because of a stratospheric failure. Literally.

In 2012, a team at X asked something crazy:

Could we connect the remotest parts of the world with high-speed Internet delivered through stratospheric Internet-beaming balloons?

That project, called Loon, failed. In disbanding Project Loon, Teller wrote:

We hope that Loon is a stepping stone to future technologies and businesses that can fill in blank spots on the globe’s map of connectivity. To accelerate that, we’ll be exploring options to take some of Loon’s technology forward. We want to share what we’ve learned and help creative innovators find each other — whether they live amidst the telcos, mobile network operators, city and country governments, NGOs or technology companies.

Stepping stone. It’s that same phrase that Stanley and Lehman, the two theorists from Why Greatness Cannot be Planned, used.

World-changing ideas don’t always work out. Scratch that. Most world-changing ideas fail. But their failure can be serendipitous. Their residue is rich fertilizer for the soil of creativity for the next moonshot. Failure is learning.

While working on Loon, the leader of the team, Mahesh Krishnaswamy, had an epiphany: Could we deliver on the ambition of that same moonshot not in the skies but on the ground?

In 2016, Project Taara kicked off to connect those least able to pay to the world by laser beams. And one of the earliest pilots of that moonshot is now happening in the village where Krishnaswamy used to spend his summers.

Pic credit: Project Taara @ X

If it works out, the technology will travel to congested cities because ground-based Internet infra of fiber optics is cumbersome and expensive. All because of a whopping failure.

What’s wrong with how most corporations shoot for the stars?

Project Loon failed. From its ashes took root Project Taara. And now it’s going to change the world. Krishnaswamy and his team didn’t see this coming but they also didn’t give up on learning from the experience. They found a way to compost failure.

Look beyond this singular instance of exaptation, and you may see that the ruins of tens of abandoned projects at X carry the lushest insights gathered over years. Such an ecosystem is uncommon in corporate life.

When shooting for the stars, it helps to look beyond pass-fail. Annie Duke, decision strategist and author, suggests in her book Quit that we do the mental math differently. Not in terms of how short of the target you ended up but how far you landed from your starting point.

In most organizations trying to take a new product/service idea from 0 to 1, the pass-fail nature of goals is the yardstick in use. Executives, especially if they’ve been successful before, have a hard time sufficiently accounting for uncertainty in planning. Because executives don’t sufficiently appreciate uncertainty and account for it, they are not alert to learning because of it. Instead they focus on metrics and annual projections, and ignore the dancing monkey that refuses a word of instruction. And because they don’t learn, or they don’t learn quickly enough, they keep building pedestals until the clock runs out.

Failed projects demand a wave of restructuring. Teams change, personnel change, and a new project kicks off. The remnants of learning from past projects are lost, or even discarded in disregard of Chesterton’s fence. The new team begins, or chooses to begin, from a blank page. There’s little ‘moonshot compost’ to feed the growth of the next project.

Perpetuate such behavior, and we see ambitious corporations that promise the moon to investors and shareholders continually downgrading expectations. Down from revolutionary new tech, down from double-digit annual growth projections. It is the curious corporations that steal a march over them.

Perhaps, paradoxically, it is the most curious organizations that are truly ambitious.

Can greatness be planned or is it unplannable?

Last week I raised a toast to aimless wandering. To the virtues of following our curiosity. To using stepping stones as a unit of innovation and to continue building bigger edifices of human progress.

This week I reflect on how greatness needs to be planned to the breakthrough point. Define the bottleneck that needs to be removed to realize the full potential of our best ideas, and be ready to scrap the whole thing if that’s not possible. And if that does come to pass, it’s not wasted time and energy. Put it down as a valuable experiment, the lessons of which gives the next team of inventors a head start.

Where the two theories unite is that they are both mechanisms to deal with uncertainty. While one proposes embracing it and being okay with going where serendipity pulls you, the other suggests accepting uncertainty and then defining the range within which you’re prepared to face it and beyond which you’re ready to walk away.

Humans share a visceral response to uncertainty. Uncertainty triggers an aversion to loss. Never mind the transformative potential of a radical idea. We can and do look past it all the time. We are deeply guided by our worries. And here we have two proven ways of dealing with uncertainty, which are in essence saying the same thing: accept uncertainty, embrace it, make the most of it.

It matters less whether we pick the path of curiosity or monkey-training for the pursuit of our deepest ambitions. What matters is that we enjoy the thrill of the chase.

Thank you for your attention 🙏 What did you make of this issue? Let me know in the comments!

Finally, a couple of updates.

📢I had the privilege to contribute a guest post for my good friend

’s newsletter Stay Curious. It’s got some actionable advice for three common work situations. Take a look at that and other issues if you have time. Pritesh does some top-notch curation anyway.📢Last week, I had put out a call for those in this community of the curious who wanted to be a part of a private community for keen decision-makers. While I’ve started testing out modalities for communication, I realize that a bunch of you may have missed the news or may have joined more recently. If the idea sounds appealing, you can confirm your interest at satyajit@satyajitrout.com. I plan to get this rolled out soon.

Until then, stay well!